Topic: Canadian Army

The Battle of Kiska

In an Aleutians Islands operation in 1943, U.S. and Canadian troops found themselves pitted against three Japanese dogs.

Kiska Capture Puts Allies On Road To Tokyo

The Ottawa Citizen; 23 August, 1943 — (excerpted)

Canadians Involved

The Canadian Fusiliers of London, Ont., under Lt.-Col. Russell H. Beattie, M.C., 48, London, Ont.

The Winnipeg Grenadiers under Lt.-Col. J.A. Wilson, Winnipeg, who returned from overseas to take over this reconstitution of the original battalion which served at Hong Kong.

The Rocky Mountain Rangers, an interior British Columbia unit under Lt.-Col. D.B. Holman, M.C., 48, Salmon Arm, B.C.

Le Regiment de Hull (Que,.) under Lt.-Col. Dollard Menard, D.S.O., 30, Quebec, one of the heroes of last summer's Dieppe battle.

A company of the St. John (N.B.) Fusiliers under Maj. G.P. Murphy, 27, Saint John.

The 24th Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery, under Lt.-Col. R.P. Drummond, 50, Spencerville, Ont., and Montreal.

The 46th Light Anti-Aircraft Battery under Maj. J.A. MacDonald, 51, Burlington, Ont.

The 24th Field Company of the Royal Canadian Engineers under Maj. D.H. Rochester, 27, Toronto.

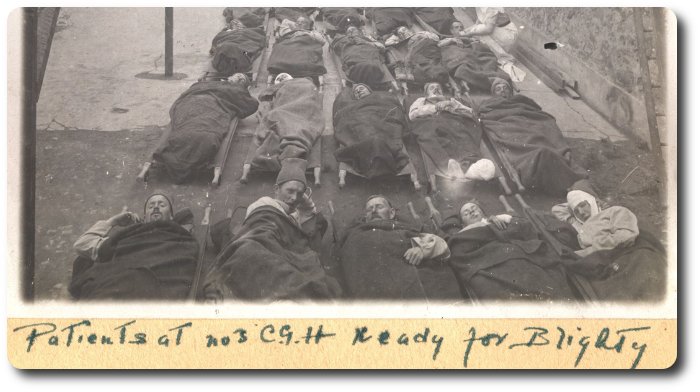

The 25th Field Ambulance of the Royal Canadian Medical Corps under Lt.-Col. T.M. Brown, 40, Calgary and Ottawa.

In addition there were detachments from Ordnance, Army Service, Provost, Pay and Postal Corps.

The Kiska operation was the first in the Aleutians in which Canadian soldiers have taken part but Canadioan naval and air personnel have served there previously.

Many of the Canadian personnel were men were men called up for compulsory military service inder the national Resources Mobilization Act.

The Ottawa Citizen; 3 January 1956

By Warren Baldwin, Southam News Services

On August 15, 1943, an assault force of 29,000 Americans and 5,300 Canadians was dispatched to attack a Japanese force of three dogs.

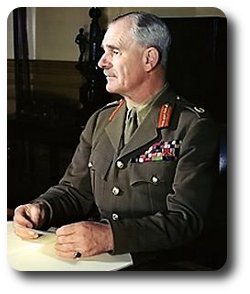

The story of the occupation of the Aleutian Island of Kiska, gleaned for the first time from both Japanese and Canadian military records, in included in the first volume of the official history of the Canadian army in the Second World War. The author, C.P. Stacey, Director of the Historical Section, General Staff, labels it "Fiasco at Kiska."

The story confirms finally the fact that the Japanese had been evacuated from Kiska under cover of fog 18 days before the Canadian-American operation was scheduled to start. The decision to evacuate was not taken because of any knowledge of the assault but because the Japanese believed the forces occupying the island could be employed more usefully in the Kuriles, nearer home. It also strengthens Colonel Stacey's conclusion that at no time during the war did the Japanese have any plans for a full scale attack on Canada's west coast.

Political Motive

The Aleutian campaign to get the Japanese off Attu and Kiska, Colonel Stacey says, was more political than military. On the map, he points out, the Aleutians seem to form a natural bridge from Asia to North America, but appearances are deceptive. From the most westerly island, Attu, to Dutch Harbour is 800 miles and from Dutch Harbour to Vancouver, 1,650 miles. It might have been better, he suggests, to "leave the japs to freeze in their own juice on Kiska and Attu, where they were at most a nuisance to American operations in the Pacific."

But the people of Alaska and British Columbia were alarms and critical and both Ottawa and Washington were concerned. Stacey reports elsewhere that by February, 1942, "public opinion on Canada's Pacific Coast was in a state approaching panic." The Vancouver Sun was prosecuted under Defence of Canada Regulations in March for suggesting that Ottawa was treating British Columbia as expendable.

Attu was occupied in May, 1943, by the American 7th Division after "a nasty little campaign in which the Japanese fought to be killed and the Americans obliged them"

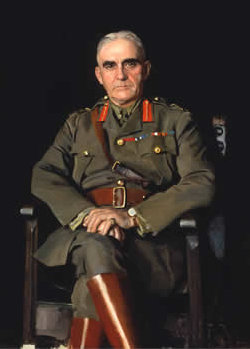

Canadian participation in the Kiska campaign of one brigade group was requested formally in a letter from Secretary of War Stimson to Defence Minister Ralston on May 31, 1953. The 13th infantry brigade formed for the purpose under the command of Brigadier H.W. Foster consisted of the Canadian Fusiliers, the Winnipeg Grenadiers (reformed after Hong Kong), the Rocky Mountain Rangers and Le Regiment de Hull. In addition, the first battalion of the U.S.-Canadian Special Service Force was brought up from a United States training base to join the operation.

There was plenty of evidence, Colonel Stacey points out, to indicate that the Japanese had evacuated previously. RCAF planes on August 11 reported no sign of life. But trickery was suspected. Major-General G.R. Pearkes, the Commander-in-Chief of Pacific Command, whoi had set up advanced headquarters at Adak, wrote afterwards that it was thought the enemy had evacuated main camps and moved to battle positions on the beaches and hills.

Island Empty

It took four days for the troops to realize that they had landed on an empty island. Japanese records state that nothing had been left on the island but three dogs.

One reason behind Ottawa's decision to participate was the opportunity to use draftees under the National Resources Mobilization Act on active service in order to break down the hostile attitude of the public toward "zombies". The Kiska affair, Stacey comments, had no such result, which was "particularly regrettable as the NMRA men behaved admirably."

There had been some suggestion of a reconnaissance of the island by boat to check on air force reports, but this was not done.

"In the light of hindsight," he says, "this decision seems unfortunate. It was a pity to give the enemy the satisfaction of laughing at us."

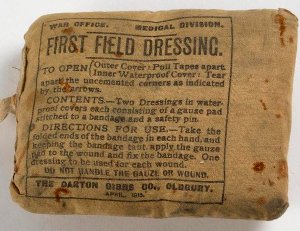

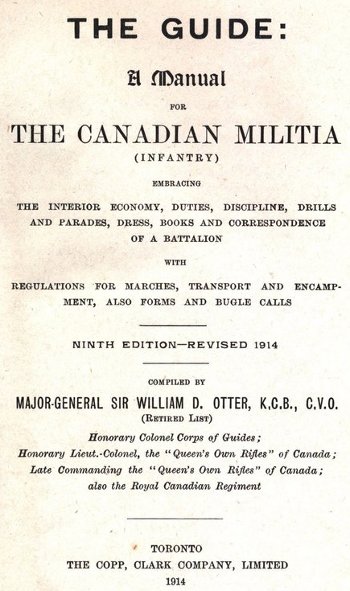

1. Every officer and man will carry on a string round his neck an identity disc showing his name, number if any, unit and religion. He will also carry a first field dressing in the right hand skirt pocket of his coat. Both disc and dressing should be frequently inspected.

1. Every officer and man will carry on a string round his neck an identity disc showing his name, number if any, unit and religion. He will also carry a first field dressing in the right hand skirt pocket of his coat. Both disc and dressing should be frequently inspected.

Before dealing with the attempts to modernise our infantry … it seems important to decide what the true role of the infantry is. Here are some that have been suggested in various quarters:—

Before dealing with the attempts to modernise our infantry … it seems important to decide what the true role of the infantry is. Here are some that have been suggested in various quarters:—

The pioneers are a small section of regimental artificers, competent to repair barracks, furniture, utensils, etc., or do minor mechanical work in barracks or camp, and if need be, instruct others in the same. They should be selected mainly on account of proficiency in their trades, and good character; they may also be employed in the Quarter-Master's store or other duty pertaining to that department.

The pioneers are a small section of regimental artificers, competent to repair barracks, furniture, utensils, etc., or do minor mechanical work in barracks or camp, and if need be, instruct others in the same. They should be selected mainly on account of proficiency in their trades, and good character; they may also be employed in the Quarter-Master's store or other duty pertaining to that department.

Britton says he craves a

Britton says he craves a

The regiments which escape disbandment or conversion, but practically all of them amalgamated with some other unit, follow:

The regiments which escape disbandment or conversion, but practically all of them amalgamated with some other unit, follow: Ontario: Canadian Fusiliers, London; the Kent Regiment, Chatham; the Perth Regiment, Stratford; the Queen's York Rangers, the Toronto Scottish and the Irish Regiment of Canada, all of Toronto; the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders of Canada, Hamilton; the Sault Ste. Marie and Sudbury Regiment, Sault Ste. Marie; the Princess of Wales Own Regiment, Kingston; the Prince of Wales Rangers, Peterborough; and the Cameron Highlanders of Ottawa.

Ontario: Canadian Fusiliers, London; the Kent Regiment, Chatham; the Perth Regiment, Stratford; the Queen's York Rangers, the Toronto Scottish and the Irish Regiment of Canada, all of Toronto; the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders of Canada, Hamilton; the Sault Ste. Marie and Sudbury Regiment, Sault Ste. Marie; the Princess of Wales Own Regiment, Kingston; the Prince of Wales Rangers, Peterborough; and the Cameron Highlanders of Ottawa. Unaffected by the reorganization, and continuing presumably as infantry rifle battalions are 43 regiments:

Unaffected by the reorganization, and continuing presumably as infantry rifle battalions are 43 regiments:

Ottawa, August 4.—A unique military proposition is at present being urged upon the Hon.

Ottawa, August 4.—A unique military proposition is at present being urged upon the Hon.

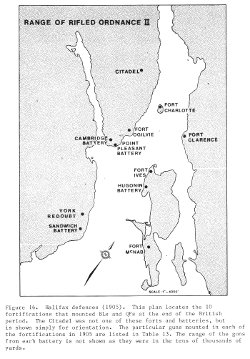

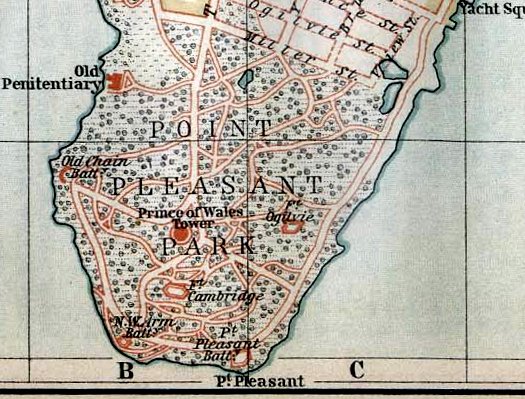

And there are more fortifications than the casual tourist can see from the harbor. I had been in Halifax for a day and was driving through

And there are more fortifications than the casual tourist can see from the harbor. I had been in Halifax for a day and was driving through