Topic: Army Rations

Combat Ration Program

Excerpted from Food and beverage consumption of Canadian Forces soldiers in an operational setting: Is their nutrient intake adequate?; Pamela Hatton, School of Dietetics and Human Nutrition, McGiII University, Montreal, September 2005

CR Combat ration

CRP Combat Ration Program

DRI Dietary Reference Intakes

IMP Individual Meal Pack

LMC Light Meal Combat

Canadian combat rations are shelf-stable foods designed and developed to meet military members' physical and dietary requirements, while incorporating Canadian cultural food preferences as well as common preferences of the military members. As a primary alternative to a freshly prepared meal, combat rations are used when it is not feasible or practical to serve fresh rations. Specific training or exercise purposes, rapid-response emergency situations and when over-riding practical considerations preclude the use of fresh food necessitate using combat rations. Combat rations are designed for healthy Canadians who do not require special therapeutic dietary needs and are not subject to food allergies, food intolerance or food sensitivity. The meal components offer common foods based on Canadian eating patterns (DND 2002).

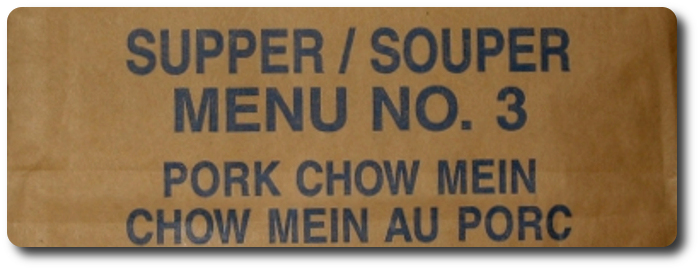

The food components of the Combat Ration Program include Individual Meal Packs, Light Meal Combat, arctic and tropical supplements and survival packets. The Individual Meal Pack (IMP) is shelf-stable for three years and identified by meal (breakfast, lunch and supper). The intent of the IMP is to provide a nutritionally adequate diet, including sufficient energy and other nutrients for up to 30 days without supplementation with fresh rations. Ali components of the IMP are prepared or require limited food preparation or reconstitution. The retort pouch packaging of the main entrée allows eating the contents unheated or heated in boiling water or by body heat. Eating the entire three meals per day provides between 3600 to 4100 kcal. Macronutrient composition ranges between 35-65 g of protein, 188-282 g of carbohydrate and 18 to 62 g of fat per complete meal (DND 2002).

The Light Meal Combat (LMC) component supplements IMPs when arduous activity or severe weather conditions warrant extra energy intake. The LMCs can also substitute for IMPs for a maximum of 48 hours when the situation precludes carrying, preparing or disposing of IMP components. The LMC menus range between 1300 to 1471 kcal with 25 to 33 g of protein, 25 to 39 g of fat and 213 to 256 g of carbohydrate per package (DND 2002).

In extreme climatic conditions, the arctic supplement or the (tropical) ration supplement can provide additional nutrients, energy and fluids (DND 13/1272002). The starch jelly composition of the basic survival packet provides emergency sustenance for two days. The air survival food ration consists of the basic survival food packet and hot beverages for a period of three days. The Maritime survival ration includes two jelly food packets and a fresh water ration providing emergency sustenance for five days (DND 2002).

Recommendations for adequacy

The nutrient density of IMPs needs to be increased, to ensure that all dietary reference intakes (DRI) can be met. Too often, foods contributing significant nutrients are not necessarily identified as high nutrient sources as seen in the "top ten foods" table (Table 8). By offering the IMPs and LMCs together, the total nutrient profile of the combat rations improves with potential energy at ~5500 kcal, fibre at 36 g and potassium at ~5000 mg. As seen with the extent of discarded or "stripped" foods before going to the field, simply increasing the quantity of menu offerings does not translate to consuming enough food. Individuals choose what they think they need and do not necessarily make appropriate choices. As a result, a majority (78%) of Exercise Narwhal subjects did not meet the target amount of ~580 g carbohydrate/day for military manoeuvres (Jacobs, Anderberg et al. 1983; Jacobs, van Loon et al. 1989). The reality of soldiers discarding or "stripping" rations needs addressing. Since many potential nutrients are thrown out, such as the rarely consumed potatoes, rice and puddings, these nutrients need replacing with foods that soldiers will eat under operational requirements.

Feeding the Troops; Rural vs. City Corps

Feeding the Troops; Rural vs. City Corps

a. The garrison ration is that which the Government prescribes in time of peace for all persons entitled to a ration except under special circumstances when other rations are prescribed. The different items such as meat, fresh vegetables and fruit, beverages, bread, and other articles of food which make up that ration are called "ration components." The number af components and the amount of each required to give a soldier a well-balanced and nourishing daily diet have been carefully determined by food experts. The money value of the ration is figured each month from the wholesale costs of food to the Government, and your organization mess account is credited with the total amount required to feed a1l the men in your unit. The meals served by your organization mess sergeant in time of peace, and while Your organization is in a post, camp, or cantonment, will usually be prepared from the components of the garrison ration. After the mess sergeant has made up his menus he will buy the various articles of food required from the money which the Government has credited to your organization mess account. Some of these items he may buy from the quartermaster commissary. Others he may buy from local markets or farmers, in order to take advantage of certain foods in season or because the commissary may not have them in stock. Any savings which he makes are called "ration savings'' and become part of your unit mess fund, to be expended by your organization commander on extras for the mess on holidays or other special occasions.

a. The garrison ration is that which the Government prescribes in time of peace for all persons entitled to a ration except under special circumstances when other rations are prescribed. The different items such as meat, fresh vegetables and fruit, beverages, bread, and other articles of food which make up that ration are called "ration components." The number af components and the amount of each required to give a soldier a well-balanced and nourishing daily diet have been carefully determined by food experts. The money value of the ration is figured each month from the wholesale costs of food to the Government, and your organization mess account is credited with the total amount required to feed a1l the men in your unit. The meals served by your organization mess sergeant in time of peace, and while Your organization is in a post, camp, or cantonment, will usually be prepared from the components of the garrison ration. After the mess sergeant has made up his menus he will buy the various articles of food required from the money which the Government has credited to your organization mess account. Some of these items he may buy from the quartermaster commissary. Others he may buy from local markets or farmers, in order to take advantage of certain foods in season or because the commissary may not have them in stock. Any savings which he makes are called "ration savings'' and become part of your unit mess fund, to be expended by your organization commander on extras for the mess on holidays or other special occasions.

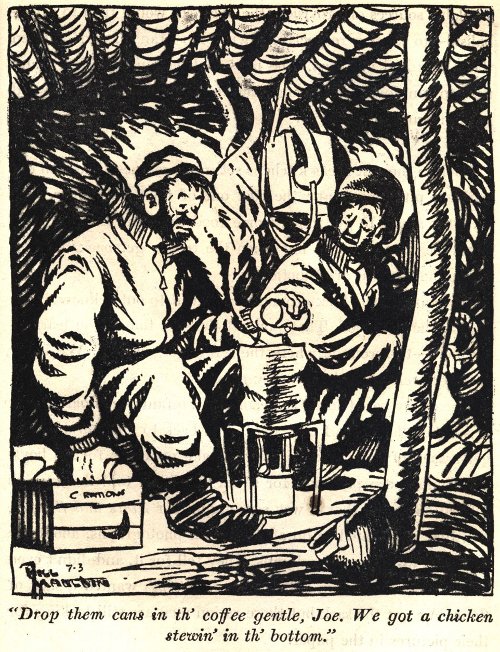

[Drivers of the Royal Canadian Army Service Corps] also learned the art of "brewing-up"—something we didn't know anything about until we joined the 8th Army.

[Drivers of the Royal Canadian Army Service Corps] also learned the art of "brewing-up"—something we didn't know anything about until we joined the 8th Army.

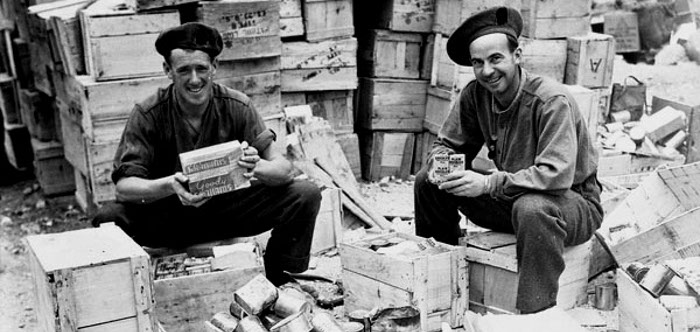

The mess tin ration or 48-hour ration provides subsistence for the first 48 hours after landing.

The mess tin ration or 48-hour ration provides subsistence for the first 48 hours after landing. Ration Allowances.

Ration Allowances.

This email text has been floating around the Internet for a few years. It offers an excellent, though possibly apocryphal, description of what can happen when an unprepared and unacclimatized digestive system meets army field rations. Thanks to Ranger Rodgers, wherever he may be.

This email text has been floating around the Internet for a few years. It offers an excellent, though possibly apocryphal, description of what can happen when an unprepared and unacclimatized digestive system meets army field rations. Thanks to Ranger Rodgers, wherever he may be.