Topic: Soldiers' Load

To Test New Equipment (US Army, 1911)

The Milwaukee Sentinel, 27 March 1911

The maneuvres of the United States army along the Mexican border will afford an opportunity to try out the more modern and lighter personal equipment for the individual soldier. Ever since military experts began a real study of conditions with the intention, if possible, of lightening the infantryman's burden, the one foremost idea has been in lessening the number of pounds of accoutrements necessarily carried when under full field equipment. Full field equipment is the new and official term used in place of the old heavy marching order.

Under the present army regulations the full field equipment for active service, including rifle and ninety rounds of ammunition, weighs fifty-four pounds. Although some reports of the mobilization have said that each man received 200 rounds, it was pointed out by an expert that while the particular organization of troops carried such a supply with them, only the prescribed ninety rounds were doled out to each soldier. Only in extreme cases—that is, when a body of men are to be immediately engaged in actual battle—are the extra cartridges supplied.

With fifty-four pounds as the present weight of the individual equipment for an infantryman, it is the hope of the military experts to reduce that from fifteen to seventeen pounds; but the ever present idea remains in their mind, namely, that an equal efficiency must be obtained from the lighter articles. The use of aluminum plates, knives, forks and spoons, together with haversacks, tent halves, ponchos, tent poles, etc., of lesser weight, it is thought will bring down the total number of pounds per man.

Under the present ruling a soldier carries besides hi piece, a Springfield magazine rifle which weighs nine and a half pounds, and ninety rounds of cartridges which weigh four and a half pounds, a bayonet, bayonet scabbard, a rifle sling, cartridge belt, a pair of cartridge belt suspenders which tend to lessen the weight by help from the shoulders, a first aid packet, a canteen and strap, a set of blanket roll straps, a haversack, a meat can, once cup, one plate, one knife, one fork, one spoon, half a shelter tent, one tent pole and five tent pegs. Then in addition to that comes his field kit, the weight of which is included in the total fifty-four pounds; consisting of a blanket, a poncho and personal effects, such as a comb, toothbrush, towel, extra underclothing, soap, etc.

But besides the soldier's individual load there are intrenching tools which are given out and carried by company and squad. A full company is made up of 108 men and officers in time of war and sixty men and officers in time of peace. A squad, the second unit of a company, consists of eight men. The intrenching tools are four hand picks, to be carried by company, a pick mattock per squad, three shovels per squad, three wire cutters per company and a two foot folding rule per company. These tools are an addition to the fifty-four pounds and the soldiers take turns in carrying them.

Most of the troops in the Mexican border war game are equipped with the fifty-four pound outfit; but enough are using the lighter articles to insure a thorough tryout.. Tin plates, meat cans, etc., instead of aluminum ones are the staple mess equipment carried by the majority of these soldiers.

Ottawa, January 14.—The year's work in the Canadian Militia is reviewed in the annual report of the Militia Council presented by Colonel the Hon. Samuel Hughes. The one object sought, says the report in part, was preparedness for war, the power to mobilize at short notice a force of adequate strength, well-trained and fully equipped. In the scheme of defence a few adjustments have been made, but no important changes introduced.

Ottawa, January 14.—The year's work in the Canadian Militia is reviewed in the annual report of the Militia Council presented by Colonel the Hon. Samuel Hughes. The one object sought, says the report in part, was preparedness for war, the power to mobilize at short notice a force of adequate strength, well-trained and fully equipped. In the scheme of defence a few adjustments have been made, but no important changes introduced. "The main obstacles to our efficiency," remarks General Otter, "present themselves in two forms—lack of money on the one hand and the profusion of it in the form of successful enterprises on the other. The former, militating against the provision of armories and equipment, rifle ranges and training grounds, and so placing obstacles in the prosecution of effective training in its full significance; the latter prevents individuals from sparing the time necessary to fit themselves for the military duties they have assumed."

"The main obstacles to our efficiency," remarks General Otter, "present themselves in two forms—lack of money on the one hand and the profusion of it in the form of successful enterprises on the other. The former, militating against the provision of armories and equipment, rifle ranges and training grounds, and so placing obstacles in the prosecution of effective training in its full significance; the latter prevents individuals from sparing the time necessary to fit themselves for the military duties they have assumed."

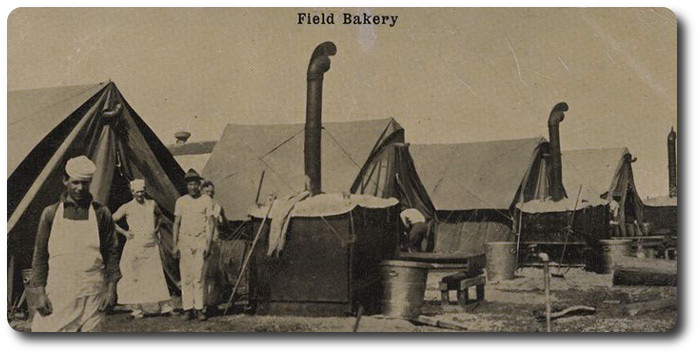

The Commissary Department of the Army of the United States has been brought to perfection and the American soldier is better fed than the man who bears arms under any other flag on earth.

The Commissary Department of the Army of the United States has been brought to perfection and the American soldier is better fed than the man who bears arms under any other flag on earth.

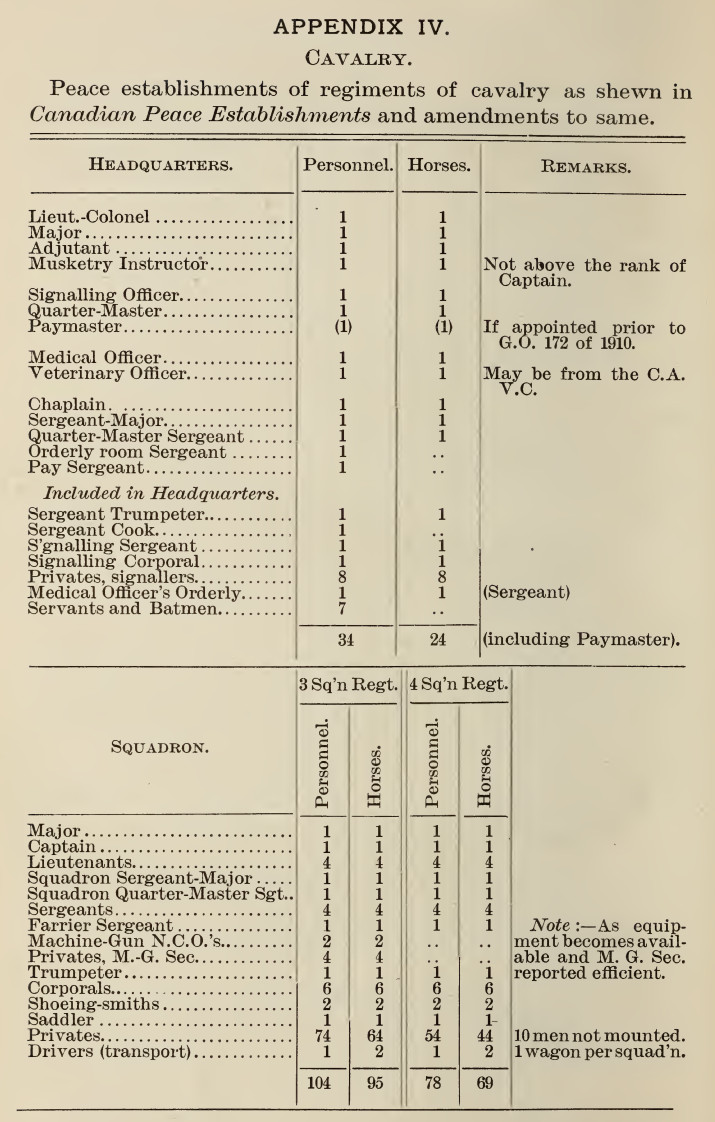

Headquarters

Headquarters

In 1867, there came to Canada, as the senior Staff Officer, a brilliant young soldier who, though but 34 years of age, had already seen service in the Crimea, at the Relief of Lucknow and in China, and who, in 1870, was chosen by Ottawa to command the Red River Expedition to the then almost unknown Canadian West, where the rebel Louis Riel headed an uprising to establish a Republic of North-West Canada.

In 1867, there came to Canada, as the senior Staff Officer, a brilliant young soldier who, though but 34 years of age, had already seen service in the Crimea, at the Relief of Lucknow and in China, and who, in 1870, was chosen by Ottawa to command the Red River Expedition to the then almost unknown Canadian West, where the rebel Louis Riel headed an uprising to establish a Republic of North-West Canada. The School was formerly opened on the 31st March, 1888, with Colonel Henry Smith, a veteran of the North-West Rebellion of 1885, as Commandant, and the barracks became headquarters of "D" Company, Royal Infantry (sic). The establishment of the School was six Officers and one hundred N.C.O.'s and men, many of whom were recruited locally; and then started the first courses of instruction.

The School was formerly opened on the 31st March, 1888, with Colonel Henry Smith, a veteran of the North-West Rebellion of 1885, as Commandant, and the barracks became headquarters of "D" Company, Royal Infantry (sic). The establishment of the School was six Officers and one hundred N.C.O.'s and men, many of whom were recruited locally; and then started the first courses of instruction.

Washington, Sept. 20.—The General Staff of the army is hard at work on the new manuals for the sabre and the bayonet for the army. Hitherto these manuals have called for much skill on the part of enlisted men, so much, indeed, that few of them can acquire the art of wielding either weapon in a satisfactory manner. It is proposed to omit from the manuals everything of a fancy fencing character, such as is taught in the private drillrooms. It is intended that there shall be a return to the simplest methods, and that everything shall be on the most practical and useful basis. Both weapons are meant for use in time of war, and especially is this so of the bayonet. The officers who have been on duty in Manchuria with the Russian and Japanese armies are furnishing special reports to the General Staff on the subject, and such experts as Captain Herman J. Koehler, the master of the sword at the Military Academy, and Civil Engineer Cunningham, of the navy, who is an expert swordsman, and who had charge of the Naval Academy fencing last year, are also giving valuable advice along the line indicated. The War Department recently adopted a new type of sabre, which will be kept with a sharpened edge and carried in a wooden scabbard. A new bayonet was adopted several weeks ago, based on the results of the observations of our military attaches with the troops in Manchuria. The sabre and bayonet are therefore of fighting value, and the manual will be of a kindred practical spirit.

Washington, Sept. 20.—The General Staff of the army is hard at work on the new manuals for the sabre and the bayonet for the army. Hitherto these manuals have called for much skill on the part of enlisted men, so much, indeed, that few of them can acquire the art of wielding either weapon in a satisfactory manner. It is proposed to omit from the manuals everything of a fancy fencing character, such as is taught in the private drillrooms. It is intended that there shall be a return to the simplest methods, and that everything shall be on the most practical and useful basis. Both weapons are meant for use in time of war, and especially is this so of the bayonet. The officers who have been on duty in Manchuria with the Russian and Japanese armies are furnishing special reports to the General Staff on the subject, and such experts as Captain Herman J. Koehler, the master of the sword at the Military Academy, and Civil Engineer Cunningham, of the navy, who is an expert swordsman, and who had charge of the Naval Academy fencing last year, are also giving valuable advice along the line indicated. The War Department recently adopted a new type of sabre, which will be kept with a sharpened edge and carried in a wooden scabbard. A new bayonet was adopted several weeks ago, based on the results of the observations of our military attaches with the troops in Manchuria. The sabre and bayonet are therefore of fighting value, and the manual will be of a kindred practical spirit.

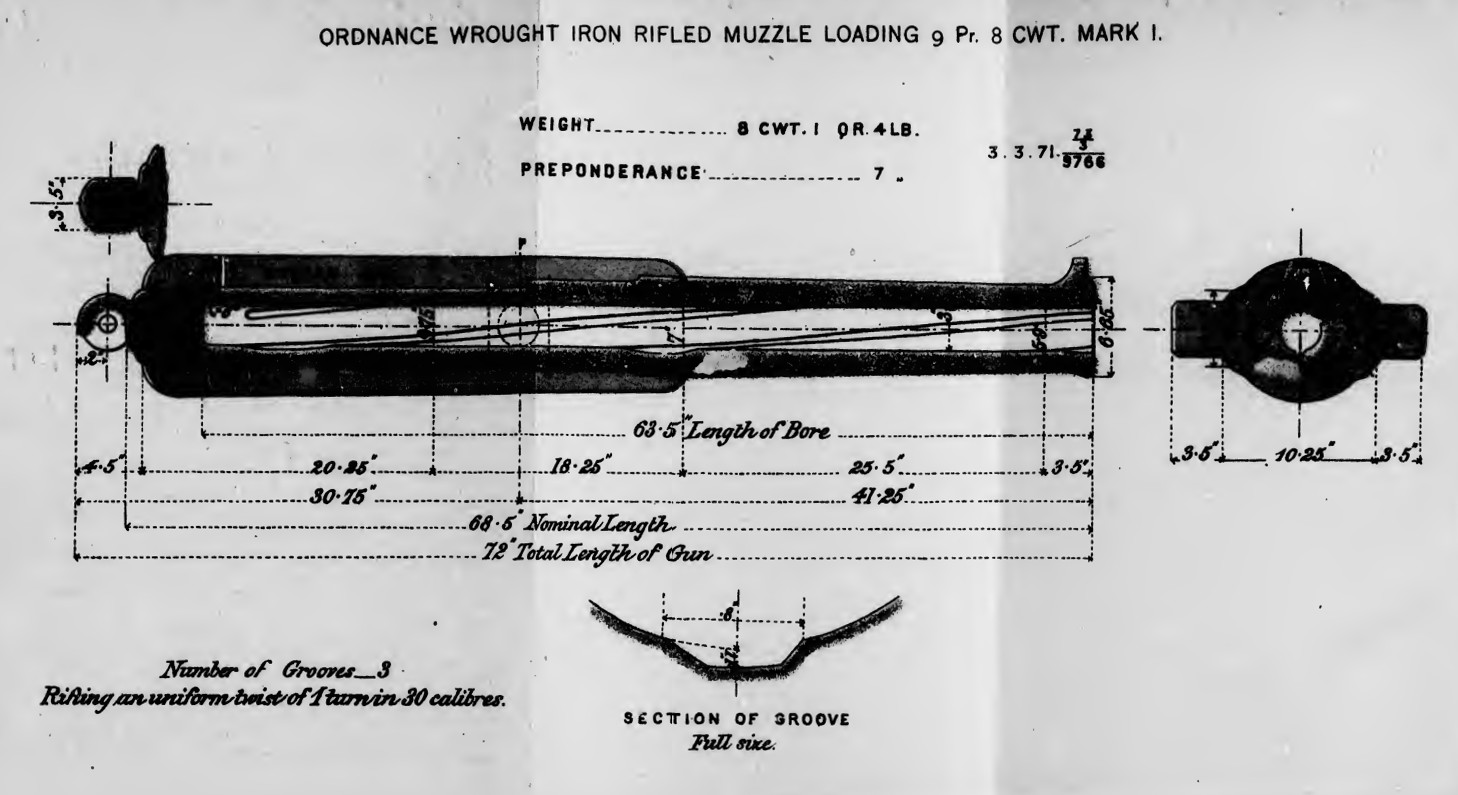

Designation.—Ordnance, wrought Iron rifled, M.L. 9 Pr. 8 cwt.

Designation.—Ordnance, wrought Iron rifled, M.L. 9 Pr. 8 cwt.

Cavalry.—The horse moves 400 yards at a walk, in about 3.9 minutes; at a trot in about 2 minutes; at a gallop in 1.4 minutes. His stride in walking is about 0.917 yards; at a trot 1.23 yards; at a gallop 3.52 yards. He occupies in the ranks 3 feet; in file 9 feet; in marching 12 feet. The heavy dragoon horse actually carries 270 pounds; if provided with one day's rations, 296 pounds, The light cavalry horse carries from 250 to 260 pounds, rations included. A cavalry horse should weigh about 1,000 pounds; height about 15.3 hands; girth round chest 80 inches. A day's rations for a horse is 10 pounds oats, 12 pounds hay, and 8 pounds straw in stable; 8 pounds oats, 18 pounds hay, 6 pounds straw, in billets; 32 pounds hay where no oats or bran are given; 9 pounds of oats are equal to 14 pounds bran. He will drink about 7 gallons of water daily. A horse should not be watered too early in the morning in cold weather. Horses' backs should be examined closely on saddling and unsaddling the least flinching should be taken notice of, and hot fomentations applied constantly. Kicks and contusions should be treated by hot fomentations, poultices, and cold water. A dose of physic may be necessary, depending on extent of tumefaction and pain. Sprains should be fomented; a dose of physic given, and cold water bandages applied. Cough and cold: soft diet, a fever ball with a little nitre; stimulate or blister the throat, if sore. If bleeding is necessary, rub the neck on the near side close to the throat, until the vein rises; to keep it full, tie a string round the neck, just below the middle; strike the fleam into the vein smartly, with a short stick. If the blood does not flow freely, the blow being properly struck, it may be made do so by holding the head well up, and causing the horse to move its jaws. After a march, first take off the bridles, tie up horses by headstall chains; loosen girths, turn up crupper and stirrups; sponge nostrils and eyes, and rub the head with a dry wisp; pick and wash feet, and give hay; wipe bit and stirrups. After the men have had their meal, saddles are taken off and the horses cleaned, watered, fed, and bedded. Upon the vigour with which grooming is performed, greatly depends the condition of the horse, when exposed to fatigue or exposure to the weather. Hand rubbing the legs and ears, not only till they are dry, but until the blood circulates freely, should be particularly observed.

Cavalry.—The horse moves 400 yards at a walk, in about 3.9 minutes; at a trot in about 2 minutes; at a gallop in 1.4 minutes. His stride in walking is about 0.917 yards; at a trot 1.23 yards; at a gallop 3.52 yards. He occupies in the ranks 3 feet; in file 9 feet; in marching 12 feet. The heavy dragoon horse actually carries 270 pounds; if provided with one day's rations, 296 pounds, The light cavalry horse carries from 250 to 260 pounds, rations included. A cavalry horse should weigh about 1,000 pounds; height about 15.3 hands; girth round chest 80 inches. A day's rations for a horse is 10 pounds oats, 12 pounds hay, and 8 pounds straw in stable; 8 pounds oats, 18 pounds hay, 6 pounds straw, in billets; 32 pounds hay where no oats or bran are given; 9 pounds of oats are equal to 14 pounds bran. He will drink about 7 gallons of water daily. A horse should not be watered too early in the morning in cold weather. Horses' backs should be examined closely on saddling and unsaddling the least flinching should be taken notice of, and hot fomentations applied constantly. Kicks and contusions should be treated by hot fomentations, poultices, and cold water. A dose of physic may be necessary, depending on extent of tumefaction and pain. Sprains should be fomented; a dose of physic given, and cold water bandages applied. Cough and cold: soft diet, a fever ball with a little nitre; stimulate or blister the throat, if sore. If bleeding is necessary, rub the neck on the near side close to the throat, until the vein rises; to keep it full, tie a string round the neck, just below the middle; strike the fleam into the vein smartly, with a short stick. If the blood does not flow freely, the blow being properly struck, it may be made do so by holding the head well up, and causing the horse to move its jaws. After a march, first take off the bridles, tie up horses by headstall chains; loosen girths, turn up crupper and stirrups; sponge nostrils and eyes, and rub the head with a dry wisp; pick and wash feet, and give hay; wipe bit and stirrups. After the men have had their meal, saddles are taken off and the horses cleaned, watered, fed, and bedded. Upon the vigour with which grooming is performed, greatly depends the condition of the horse, when exposed to fatigue or exposure to the weather. Hand rubbing the legs and ears, not only till they are dry, but until the blood circulates freely, should be particularly observed.