Capturing Military History---"20 Questions"

Topic: Commentary

Capturing Military History

"20 Questions"

The four questions sets follow, please make free use of them, rewrite them, share them. Record your answers, send them to your regimental historian.

We seldom think of the things we're doing in the present as historical events. This is especially so when we look at the minor, every-day things we do as individuals. "History" is what happened long ago, "history" was made by the notable few that get names in the history books. But that is a view with a strongly short horizon. Each and every day we might do something that, if not recorded in some way, can lead to an unanswered researchers' question in the future.

With my own interests in military history, medal collecting, and research, I often find myself, or others, delving into the detail of individual, often unrecorded, lives of soldiers, non-commissioned officers and officers. This then leads to general questions as professional and amateur researchers try to understand the lives of their subjects. The day to day life, including the training and experiences of soldiers, the social and cultural environment, and the changes they experienced are all subject to curiosities and questions. The problem is, that many of those details, being considered mundane by the participants, went unrecorded in any consistent manner.

This trend, undoubtedly part of the flow of human nature, permeates the research of soldiers. "Everybody did basic training, so why record that?" one might ask. But not everyone did the same basic training course, and it's those changes over time that are just as important to understand as the way basic training shapes a civilian into a soldier. And this leaves us with broadly generalized assumptions about soldiers and soldiering.

About a decade ago, I developed a set of questions to begin capturing more basic reminiscences for my regiment's records from those who were still around to record them. (Unfortunately, the received responses aren't currently available on line.) While each person may have simple singular memories of a part of his or her military career, there is much to be gained when such memories are collected from those who have served in different decades, in different locations, and on different operations (even the same operation over time, or under different employment on the same operations). The "mundane" details are the colorful infill in the tapestry of a regiment's story. The best days and the worst days get recorded, victories and defeats on every scale have their details captured. But the daily life of soldiers, in each era, especially when it includes the evolution of training and equipment, needs to be recorded at every stage to understand the soldier's experience.

These questions sets were called the "20 Questions" and there were four sets:

a. The Young Soldier,

b. The Young Officer,

c. Sergeants and Warrant Officers, and

d. Operations.

These weren't specific to my regiment, and could be used by any military unit wanting to capture some basic information for their own records. Even if you don't think this information is useful right now, imagine being tasked with writing your unit's history in ten years, how valuable would those personal memories be then, especially of those no longer available to record them. For those who study history of long ago events, the most valuable records are those recorded at the time by those who were there. If you don't think something is worth noting, write it down, you'll probably be the only person to record it.

The four questions sets follow, please make free use of them, rewrite them, share them. Record your answers, send them to your regimental historian (or save them with instructions in your will for them to be sent to the appropriate recipient, to protect the innocent).

20 Questions - The Young Soldier

Please provide: Name, rank achieved, years of service (from - to)

1. What year were you recruited?

2. Where did you take your basic training and how many weeks did the course run?

3. Where did you take your basic infantry training and many weeks did the course run?

4. What weapons were you trained to use on your basic infantry training?

5. What training events do you best remember from your basic infantry training course?

6. When were you posted to the Regiment, what location were you posted to, and to what Battalion, Company and Platoon?

7. How many men were in your platoon?

8. What vehicles and weapons did the platoon have?

9. How often did you go to a live fire range in a year and what weapons did you fire each year?

10. How many men lived in the same room in the barracks? How much space did you have to yourself?

11. Approximately how many men in your platoon owned a car?

12. In general, what was your daily schedule like in garrison?

13. How often were you inspected; in your room, on the parade square?

14. What was required of you before you could leave the barracks and go downtown?

15. How much were you paid each month as a new Private?

16. How many days leave did you get each year?

17. What did you do each year for an annual fitness test?

18. What was the most useful piece of personal kit you were issued at that time?

19. What was the least useful piece of personal kit you were issued at that time?

20. When the Battalion did a Change of Command parade, how long did you spend on the parade square practicing drill?

And, for extra credit:

21. What was a usual punishment one of your roommates would get for a charge of AWOL?

20 Questions - Sergeants and Warrant Officers

Please provide: Name, rank achieved, years of service (from - to)

1. What year were you recruited? What year were you promoted to the rank of Sergeant?

2. Which Battalions of the Regiment and in which Companies have you served?

3. What units have you served in outside the four Battalions of the Regiment?

4. How many years did you spend at each rank level before you were promoted to Sergeant?

5. What leadership training did you have to take before your promotion to Sergeant? When and where did you take this training and how long was the course?

6. Were there any particular events that inspired you during your advancement to the Sergeants' and Warrant Officers' Mess?

7. What do you feel was the most valuable lesson you received as a developing leader?

8. What was your first appointment on promotion to the rank of Sergeant?

9. When you commanded a rifle section, what vehicles, weapons and equipment did your section have?

10. What was your most challenging appointment as a Sergeant or Warrant Officer?

11. What did you find most rewarding about your responsibilities as a Sergeant or Warrant Officer?

12. What training experiences have you found most rewarding for yourself and your soldiers?

13. What training experiences did you find that best promoted your professional development as an NCO?

14. What operational missions have you served on as a Sergeant or Warrant Officer?

15. What was the most useful skill you learned that was taught as essential for a Sergeant or Warrant Officer to know?

16. What was the least useful skill you learned that you were told would be essential for a Sergeant or Warrant Officer to know?

17. What type of training do you think would have been more useful to receive, or to receive more of, before being promoted to Sergeant and assuming the leadership responsibilities of that rank?

18. What job or task have you had that you think every new Senior NCO should experience?

19. If you could give advice to a young soldier starting his or her military career in the Infantry, what would you offer?

20. If you could give advice to a young NCO about to be promoted into the Sergeant's and Warrant Officers' mess, what would you offer?

And, for extra credit:

21. Accepting that "no names, no pack drill" is a time honoured practice … what was the most outrageous act you remember a peer having to present himself to the RSM to explain?

Can you provide a photograph of yourself from that period of your career?

20 Questions - The Young Officer

Please provide: Name, rank achieved, years of service (from - to)

1. What year were you recruited?

2. What was your entry plan as an officer? How long was it between enrolment and commissioning for you?

3. Where did you take your basic officer training and how many weeks did the course run?

4. Where did you take your infantry officer training and many weeks did the course(s) run?

5. What training events do you best remember from your infantry officer training?

6. When were you posted to the Regiment, what location were you posted to, and to what Battalion, Company and Platoon?

7. How many men were in your platoon?

8. What vehicles and weapons did the platoon have? What was your personal weapon?

9. How long, on average, could you expect to be a rifle platoon commander when you joined the Battalion?

10. Approximately how many young officers in the battalion lived in the barracks, and how long was it before you could request permission to move out on the economy?

11. What was the best aspect about being a platoon commander? What was your least favourite task as a platoon commander?

12. How often were you expected to be at the Officers' Mess? Daily? Weekly? Monthly?

13. How often did you attend Mess Dinners? How long were you in the dining room during the longest Mess Dinner you remember attending?

14. What standard of dress were you expected to maintain in your off-duty hours?

15. How much were you paid each month as a new officer?

16. Were junior officers often sent on additional training courses? What courses did you attend outside the battalion as a young officer?

17. What exercise or training event did you find that best promoted your development as a young officer?

18. What type training would you have liked to do more of if you'd had the opportunity?

19. Were there any particular battalion eccentricities (dress or deportment) that all officers' in your Battalion were expected to follow?

20. How often might you normally have been the Duty Officer for the Battalion or the Base? What was the oddest duty you had to perform as the Duty officer?

And, for extra credit:

21. What was the greatest number of extra duties you remember a peer getting, and, if not sworn to secrecy, what were they for?

20 Questions - Operations

Please provide: Name, rank achieved, years of service (from - to)

1. What Operation did you serve on?

2. Where did the operation take place?

3. What unit (Bn/Coy/Pl) of the Regiment were you with?

4. What rank and position did you hold?

5. What were the dates of your deployment?

6. How long did the unit spend conducting pre-deployment training? How much of this time was spent on exercises at your local base, or away from home?

7. In general, what subjects were covered during pre-deployment training? Did you receive briefings or training on the culture of the country you would be visiting?

8. How did you deploy to the theatre of operations and how long were you in transit from Canada to the operational area?

9. What was your weekly work schedule like during the operation?

10. What were the usual types of tasks you performed on a daily or weekly basis on the operation?

11. What was the weather like during your tour?

12. What were your living conditions in theatre (type of quarters, personal space allocation, numbers of personnel living together)?

13. What were the rations like during the operations (type, variety, personal opinion on general quality)?

14. Did the Battalion celebrate holidays and Regimental Days as special occasions? Do you remember any particular events that stand out in your mind?

15. What weapons and equipment did your section/platoon employ during this operation? Was any new equipment issued during the operation?

16. In a few words, can you describe your general impression of the physical terrain of the country you were in?

17. What entertainments or diversions were available during your off hours?

18. How much leave could you expect during the tour, what were your options (locations, travel of spouse) for this leave?

19. Were there any small locally available souvenirs that soldiers purchased that still remind you of the tour when you see them?

20. How did you transition out of country back to Canada? How long was it between your last 'duty' and your return to family?

And, for extra credit:

21. What medal did you receive for this operation?

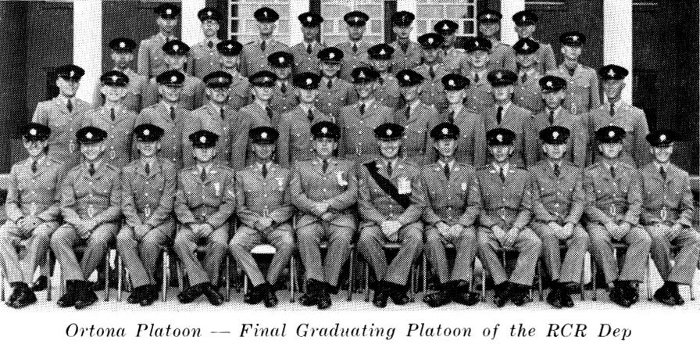

Can you provide a photograph of yourself from the operation?

Posted by regimentalrogue

at 12:01 AM EDT

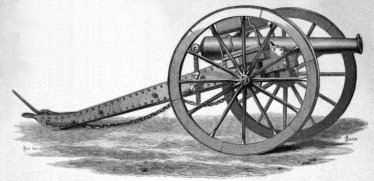

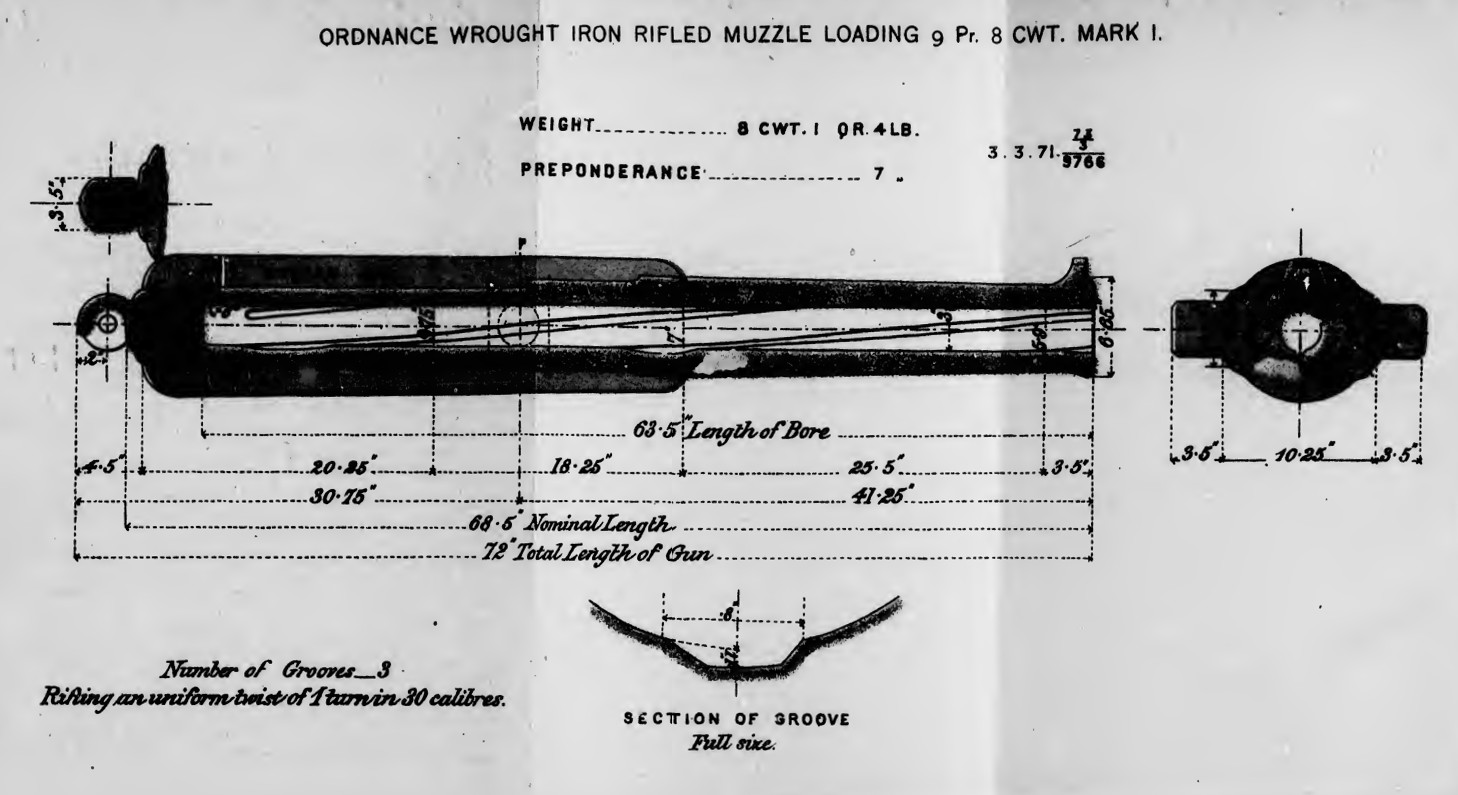

Designation.—Ordnance, wrought Iron rifled, M.L. 9 Pr. 8 cwt.

Designation.—Ordnance, wrought Iron rifled, M.L. 9 Pr. 8 cwt.

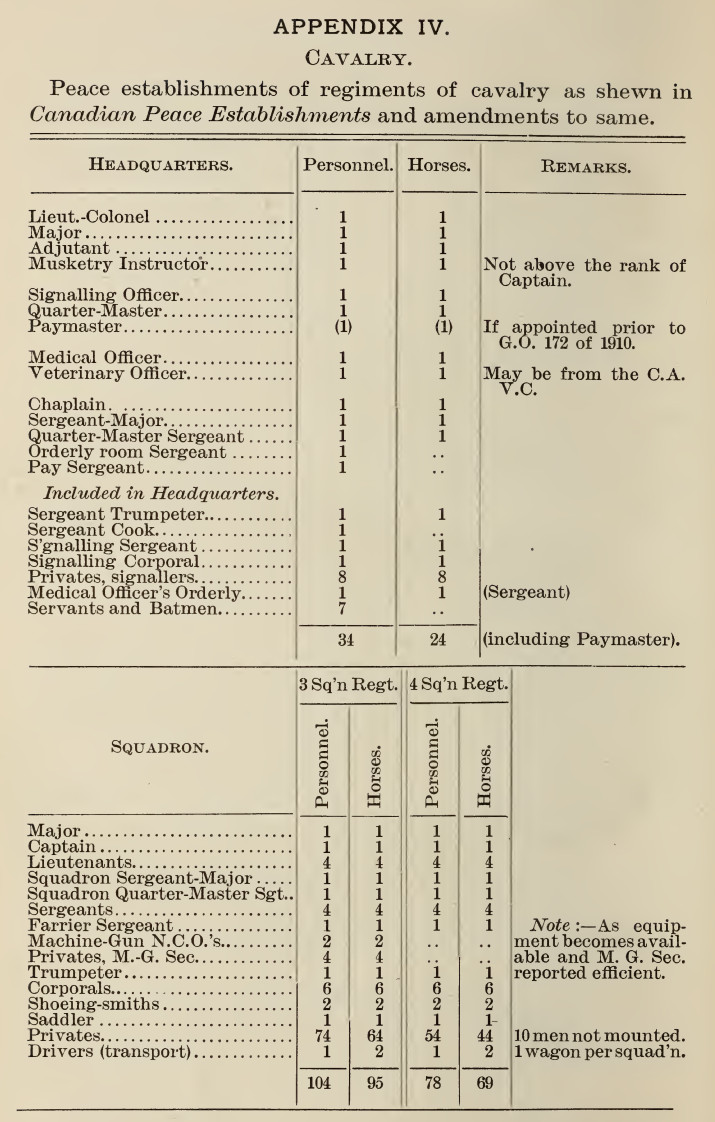

Cavalry.—The horse moves 400 yards at a walk, in about 3.9 minutes; at a trot in about 2 minutes; at a gallop in 1.4 minutes. His stride in walking is about 0.917 yards; at a trot 1.23 yards; at a gallop 3.52 yards. He occupies in the ranks 3 feet; in file 9 feet; in marching 12 feet. The heavy dragoon horse actually carries 270 pounds; if provided with one day's rations, 296 pounds, The light cavalry horse carries from 250 to 260 pounds, rations included. A cavalry horse should weigh about 1,000 pounds; height about 15.3 hands; girth round chest 80 inches. A day's rations for a horse is 10 pounds oats, 12 pounds hay, and 8 pounds straw in stable; 8 pounds oats, 18 pounds hay, 6 pounds straw, in billets; 32 pounds hay where no oats or bran are given; 9 pounds of oats are equal to 14 pounds bran. He will drink about 7 gallons of water daily. A horse should not be watered too early in the morning in cold weather. Horses' backs should be examined closely on saddling and unsaddling the least flinching should be taken notice of, and hot fomentations applied constantly. Kicks and contusions should be treated by hot fomentations, poultices, and cold water. A dose of physic may be necessary, depending on extent of tumefaction and pain. Sprains should be fomented; a dose of physic given, and cold water bandages applied. Cough and cold: soft diet, a fever ball with a little nitre; stimulate or blister the throat, if sore. If bleeding is necessary, rub the neck on the near side close to the throat, until the vein rises; to keep it full, tie a string round the neck, just below the middle; strike the fleam into the vein smartly, with a short stick. If the blood does not flow freely, the blow being properly struck, it may be made do so by holding the head well up, and causing the horse to move its jaws. After a march, first take off the bridles, tie up horses by headstall chains; loosen girths, turn up crupper and stirrups; sponge nostrils and eyes, and rub the head with a dry wisp; pick and wash feet, and give hay; wipe bit and stirrups. After the men have had their meal, saddles are taken off and the horses cleaned, watered, fed, and bedded. Upon the vigour with which grooming is performed, greatly depends the condition of the horse, when exposed to fatigue or exposure to the weather. Hand rubbing the legs and ears, not only till they are dry, but until the blood circulates freely, should be particularly observed.

Cavalry.—The horse moves 400 yards at a walk, in about 3.9 minutes; at a trot in about 2 minutes; at a gallop in 1.4 minutes. His stride in walking is about 0.917 yards; at a trot 1.23 yards; at a gallop 3.52 yards. He occupies in the ranks 3 feet; in file 9 feet; in marching 12 feet. The heavy dragoon horse actually carries 270 pounds; if provided with one day's rations, 296 pounds, The light cavalry horse carries from 250 to 260 pounds, rations included. A cavalry horse should weigh about 1,000 pounds; height about 15.3 hands; girth round chest 80 inches. A day's rations for a horse is 10 pounds oats, 12 pounds hay, and 8 pounds straw in stable; 8 pounds oats, 18 pounds hay, 6 pounds straw, in billets; 32 pounds hay where no oats or bran are given; 9 pounds of oats are equal to 14 pounds bran. He will drink about 7 gallons of water daily. A horse should not be watered too early in the morning in cold weather. Horses' backs should be examined closely on saddling and unsaddling the least flinching should be taken notice of, and hot fomentations applied constantly. Kicks and contusions should be treated by hot fomentations, poultices, and cold water. A dose of physic may be necessary, depending on extent of tumefaction and pain. Sprains should be fomented; a dose of physic given, and cold water bandages applied. Cough and cold: soft diet, a fever ball with a little nitre; stimulate or blister the throat, if sore. If bleeding is necessary, rub the neck on the near side close to the throat, until the vein rises; to keep it full, tie a string round the neck, just below the middle; strike the fleam into the vein smartly, with a short stick. If the blood does not flow freely, the blow being properly struck, it may be made do so by holding the head well up, and causing the horse to move its jaws. After a march, first take off the bridles, tie up horses by headstall chains; loosen girths, turn up crupper and stirrups; sponge nostrils and eyes, and rub the head with a dry wisp; pick and wash feet, and give hay; wipe bit and stirrups. After the men have had their meal, saddles are taken off and the horses cleaned, watered, fed, and bedded. Upon the vigour with which grooming is performed, greatly depends the condition of the horse, when exposed to fatigue or exposure to the weather. Hand rubbing the legs and ears, not only till they are dry, but until the blood circulates freely, should be particularly observed.

Boston Evening Transcript, 20 April 1905

Boston Evening Transcript, 20 April 1905

One of the most valuable contributions to the progress of medical science is undoubtedly the series of volumes recording "

One of the most valuable contributions to the progress of medical science is undoubtedly the series of volumes recording "