The Bayonet; US Army, Korea (1951)

Topic: Cold Steel

The Bayonet; US Army, Korea (1951)

Commentarty of Infantry Operations and Weapons Usage in Korea, Winter of 1950-51, S.L.A. Marshall, October 1951

… there is a tendency to credit the bayonet with almost miraculous powers as a catalyst of the fighting spirit.

More for Morale

In most of what has been reported in the American press, and in part of what has been circulated officially within the Army, the role of the bayonet in Korean operations has been stressed far beyond its intrinsic importance, when the latter is estimated in the very real terms of the battlefield and the thinking of troops about the weapon.

It is no doubt true, and subject to competent proof, that there has been more legitimate bayonet fighting by our troops in Korea than by our armies of World War I and II.

Largely because of this comparison, and partly because the upsurge of interest in the bayonet and the exaggerated wave of publicity concerning bayonet action coincided roughly with the beginning of American recovery, there is a tendency to credit the bayonet with almost miraculous powers as a catalyst of the fighting spirit.

There is nothing particularly new about this supposed connection. Indeed, it is because this view of things is so very old and traditional that it always reasserts itself upon the slightest provocation. In Korea the bayonet advocates have a considerable case based upon an impressive body of evidence—even when rumors and provedly false reports are thrown out. The main question is whether the case as it stands is being argued to a rational set of conclusions, or will serve once again to place undue training emphasis upon the weapon and what it contributes to the building of an aggressive spirit.

At least four-fifths of the reports of "fierce bayonet charges" by our troops emanating from the Korean theater are false either in whole or in part. In some instances, the troops which were described as engaging in this manner did not even possess bayonets. In others, they had bayonets and fixed them, but, during the attack, did not close with that weapon upon the enemy. One of our allies was credited in the operations of the early winter with a bloody repulse of the enemy at bayonet point in which scores were It helped inspire the new interest skewered; this story drew attention the world over. No doubt, the killing took place. But all of the attendant circumstances in the weapon. indicate that its main victims were friendly ROKs, trying to fall back into protective lines after their own position had gone; it was a case of mistaken identity.

The need for a sharp killing instrument at the end of a rifle is well indicated by the course of Korean operations; the need of a discipline which will compel troops to retain such a weapon and will enable them to use it with some efficiency when an emergency requires it is equally well indicated. Recurrently through the winter in the defense of hilltop perimeters, infantry companies were engaged with the enemy at such But killings close range that the rifle used as a spear would have taken many a victim. by Eighth Army infantry under these circumstances were so few that they could be When the rifles began to run empty and the enemy counted on one man's fingers. at last closed, with very few exceptions the men had no blade with which to stand off the rush. For lack of bayonets, they fought with clubbed rifles, stones, and sometimes with their bare fists. All of these things are in the record: the companies and individuals who so participated can be named. Oddly enough, however, the repetition of situations in which the bayonet might have proved useful did not of itself stimulate the interest of troops in the return of the weapon. The companies which had been They caught short for having thrown the bayonet away did not demand its re-issue. were not "bayonet-minded," and they seemed perfectly willing to fight again under the same odds in the next round.

1st Marine Division retained the bayonet. The Corps has continued to hold with the idea that the bayonet makes men aggressive. The entire Chosen Reservoir operation was fought at close range, with the Chinese repeatedly charging the defensive works in the night attacks and occasionally breaking the circle. Even so, the bayonet was used with killing effect in only two instances. Three Chinese were bayoneted at Hagaru-ri—all by the same man. Three, possibly four others, were either wounded or killed by the bayonet in the one assault that, managed to break into the lines at Koto-ri. The Marines make a strong display of the weapon when in defensive position. It is within They argue with some cogency that this may be one of its chief values. reason that the Chinese attacks upon Marine perimeters north of Chinghung-ni might have been pressed with even greater determination had the attackers not anticipated that they would be met with cold steel. But to attempt to justify Marine retention of the weapon, and the attendant burden, upon what the bayonet has done as a killing weapon in Marine hands during Korean operations is impossible in view of the cold figures.

The same would have to be said of results through the Eighth Army as a whole, including those non-American elements which have received especial acclaim because of their ferocity in the bayonet charge. In February, outside of Suwon, the writer visited a hill where a battalion belonging to one of our Allies was said to have killed 154 of the enemy with bayonet thrusts; these figures were publicized in the theater. Examination of the bodies made it conclusively clear that the preponderant number of the enemy dead had been killed and badly mangled by artillery fire prior to the direct assault upon the hill. In some of these bodies, there were superficial bayonet wounds. Judging by the condition of the bodies, there may have been a dozen or fewer who were eliminated by the bayonet.

Not since the rifle bullet began to dominate the battlefield has there been any sound tact'ical ground for contending that the bayonet was per se an efficient way to kill and an agency toward keeping one's own casualties low. Argument for its retention and use has been built largely around these points: (1) it creates aggressiveness in troops, (2) it instills additional fear in the heart of the enemy, and (3) troops need a last-resort weapon when other means fail.

None of these points is to be despised. If all are true as stated, they compose a valid case for retention of the weapon and a discipline serving that end. When gradual restoration of the bayonet to infantry forces was undertaken in the mid-winter of 1950-51 by the Eighth Army and lower commands, the impulse developed partly around consideration of these ideas.

But there was one other thing—the bayonet in this instance served a conspicuous need of the moment. The Eighth Army at that time was a greatly demoralized body, and lack of confidence was manifest in the ranks. The command greatly needed Restoration of the bayonet, and a something to symbolize the birth of a new spirit. Dramatizing of that action, was at, one with the simple message given to troops: "The job is to kill Chinese." Once men could be persuaded that those in other units were deliberately seeking the hand-to-hand contest with the enemy, they would begin to feel themselves equal to the over-all task.

There can be no question about the efficacy of this magic in the particular situation: it worked! But rekindling of the spirit of the Eighth Army was due even more to loud talk about the bayonet, and the power of suggestion, than to the effectiveness of such bayonet action as took place against the enemy. The benefits came from the rallying of the intangibles rather than from direct use of material means. The rapid moral recovery of Eighth Army in January is one of the true phenomena of our military history. Here there is time for reflection only on certain of its tangential aspects.

The Army had spent five weeks in retreat; the salient fact in its operations had Ranks were discouraged; having been the avoiding of close contact with the enemy. no idea what the main purpose of the nation might be, they could find none in themselves. It was an interlude of negative leadership and moral vacuum. Where a spate of words about the need for personal decision and maximum individual aggressiveness might have been received by troops as just so much bombast, emphasis on bayonet fighting served pointed notice that the period of uncertainty was over, and henceforward all ground would be contested. In combination with other techniques employed by the command and staff, it shook Eighth Army out of a state of extreme depression and gave it fresh confidence in its own power and in leadership's hold upon the general situation.

This was the significant contribution of the bayonet to the restoration of Eighth Army. It was a device toward the restoring of morale in a particular situation. But it does not follow by any means that the bayonet and bayonet doctrine make the difference between half-hearted troops and stalwart strong-going fighters in any situation.

Some of the ablest and hardest-fighting infantry companies in Korea have not taken up the bayonet and say outright that they see no good in it. They resent the effort by higher authority to persuade them to use it because they say that it is an invitation to be killed uselessly.

There are also other companies which have used the bayonet with great intrepidity during the recent months. It may be remarked of them, according to the record, that they were already combat-worthy, aggressive, and efficient in the use of their other arms before they became bayonet fighters. There is no proof whatever that the bayonet transformed them as fighters or added materially to their fighting power as a group.

Case Study

The bayonet charge by Easy Company, 27th Infantry Regiment, against Hill 180 is the one modern operation of this character which may be studied in its full detail, in the light of knowledge of the individuals concerned, their prior service in combat, their reactions, physical and emotional, during the fight, and the operational results. It therefore throws a revealing light on the general subject and particularly on the degree of emotional intensity which is required before average Americans can go all-out in bayonet fighting.

The results were truly phenomenal. One cannot help but marvel at the impetuosity of these men, once they got started forward with their rifles ready for a cutting action. But this was not an "average" infantry company nor an average man who led it. Both had already made a reputation for unusual bravery and sangfroid before ever they got together. The company included a high percentage of individuals with Spanish or Mexican-American blood; they were represented in great disproportion in the actual employment of the blade against enemy soldiers.

The mortality figures show this breakdown: Of the 18 enemy soldiers killed by the bayonet after Easy Company had closed on their foxholes, 6 met death that way because something untoward had happened to the attacker's rifle—either a misfire In four instances, the bayonet was or a failure to load consequent to the excitement. the "weapon of last resort" because one group had used up its ammunition. In most of the other killings, the men were in so close that if a bullet missed, the consequence might have been fatal.

There is no need in this writing to dilate upon the emotional stress undergone by the bayonet fighters of Easy Company or to attempt an answer to the question of whether troops could for long be sustained at such a pitch without risking total nervous breakdown. The record is the best evidence of the varying reactions of the individuals; the question is one which could be answered competently only by medical authority. But it is germane to any study of how far bayonet training and use of the bayonet in the attack should be pushed in the interests of increasing the combat quality of the Army.

The tactical omissions, which accompany and seem to be the emotional consequence of the verve and high excitement of the bayonet charge, stand out as prominently as the extreme valor of the individuals.

- The young Captain Millett, so intent on getting his attack going that he "didn't have time" to call for artillery fires to the rearward of the hill, though that was the natural way to close the escape route and protect his own force from snipers who were thus allowed a free hand on that ground.

- His subsequent forgetting that the tank fire should be adjusted upward along the hill.

- The failure to use mortars toward the same object.

- The starving of the grenade supply, though this was a situation calling for grenades, and the resupply route was not wholly closed by fire.

- The fractionalization of the company in the attack to the degree where only high individual action can save the situation, and individual ammunition failures may well lose it.

These are not entries on the debit side, or words uttered in criticism. One cannot study this fight without being reminded of the words of Justice Holmes that "heroism alone promotes belief in the supreme worth of heroism." But it is precisely because of the extreme determination of the action that its negative lessons should be held at as great value by the Army as the inspirational effects of the example.

In Summation

The main issue in regard to the bayonet is not whether troops in combat should have a knife ready for use at the end of a rifle, but how much time should be devoted to bayonet in the training schedule, and what type of blade would best suit the general purpose.

There is every advantage in equipping troops with a "last-resort weapon" provided that it is a model which they will prize for its manifest usefulness, and which, at the same time, will give them extra protection in an extreme emergency.

Of the value of the bayonet charge as a nerve tonic to troops or as an expedient in tactics, this report cannot attest. The data from Korean operations proves nothing except that given an unusual company of men, an unusually effective use of the weapon may occasionally be made. There is nothing to show that it induces phenomenal moral results when employed in the attack, either upon the using individuals or the targets; proof is lacking that in any particular situation it achieved a greater economy in operations than increased fire power might have done.

But a line of sharpened steel along the defensive line is additional insurance for the individual and may well have a profoundly deterring effect upon the enemy's resolve. If troops can be conditioned to having the blade ready for defense, they will soon form the habit of carrying it in the attack, ready for use if needed. The best results will ensue if use of the bayonet is emphasized in this order. There is no steadying value in any tactical teaching which runs counter to the common sense and instinct of the average soldier.

The Knife Bayonet

The issue bayonet is heavy, unwieldy, hard to sharpen, and harder yet to achieve a penetration with. The blade is not liked even by those units which have retained it and used it.

All infantry companies interviewed in Korea were in agreement that a knife-type bayonet for the M1 would be vastly preferable, and if a knife with a slotted handle were issued, which at the same time would serve a utilitarian purpose, troops would retain it and would fight with it. Such a knife is needed in any case for the cutting of brush, loosening of dirt, first aid, the opening of cans, and a variety of uses. The carbine knife is well thought of by troops, but they believe that an even better model could be designed.

Posted by regimentalrogue

at 12:01 AM EDT

In the article referred to it is made to appear that the permanent corps cost the country the previous year in round numbers $476,000, while the remainder of the militia cost only $211,000; as the whole militia vote for that year was $1,360,000, it might have spoiled the writer's argument, but it would have been more satisfactory to some at least of his readers, if he had told what became of the remaining $672,000.

In the article referred to it is made to appear that the permanent corps cost the country the previous year in round numbers $476,000, while the remainder of the militia cost only $211,000; as the whole militia vote for that year was $1,360,000, it might have spoiled the writer's argument, but it would have been more satisfactory to some at least of his readers, if he had told what became of the remaining $672,000.

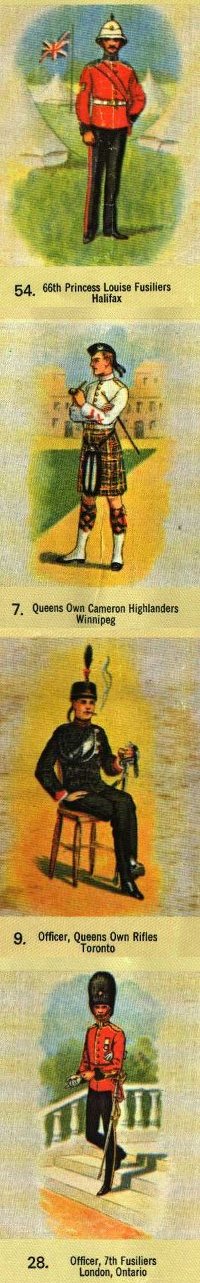

Ottawa, January 14.—The year's work in the Canadian Militia is reviewed in the annual report of the Militia Council presented by Colonel the Hon. Samuel Hughes. The one object sought, says the report in part, was preparedness for war, the power to mobilize at short notice a force of adequate strength, well-trained and fully equipped. In the scheme of defence a few adjustments have been made, but no important changes introduced.

Ottawa, January 14.—The year's work in the Canadian Militia is reviewed in the annual report of the Militia Council presented by Colonel the Hon. Samuel Hughes. The one object sought, says the report in part, was preparedness for war, the power to mobilize at short notice a force of adequate strength, well-trained and fully equipped. In the scheme of defence a few adjustments have been made, but no important changes introduced. "The main obstacles to our efficiency," remarks General Otter, "present themselves in two forms—lack of money on the one hand and the profusion of it in the form of successful enterprises on the other. The former, militating against the provision of armories and equipment, rifle ranges and training grounds, and so placing obstacles in the prosecution of effective training in its full significance; the latter prevents individuals from sparing the time necessary to fit themselves for the military duties they have assumed."

"The main obstacles to our efficiency," remarks General Otter, "present themselves in two forms—lack of money on the one hand and the profusion of it in the form of successful enterprises on the other. The former, militating against the provision of armories and equipment, rifle ranges and training grounds, and so placing obstacles in the prosecution of effective training in its full significance; the latter prevents individuals from sparing the time necessary to fit themselves for the military duties they have assumed."

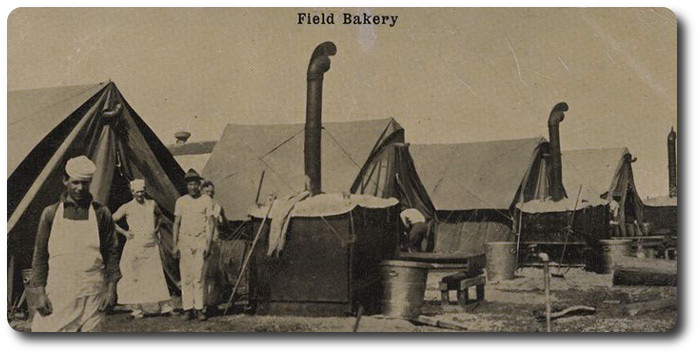

The Commissary Department of the Army of the United States has been brought to perfection and the American soldier is better fed than the man who bears arms under any other flag on earth.

The Commissary Department of the Army of the United States has been brought to perfection and the American soldier is better fed than the man who bears arms under any other flag on earth.

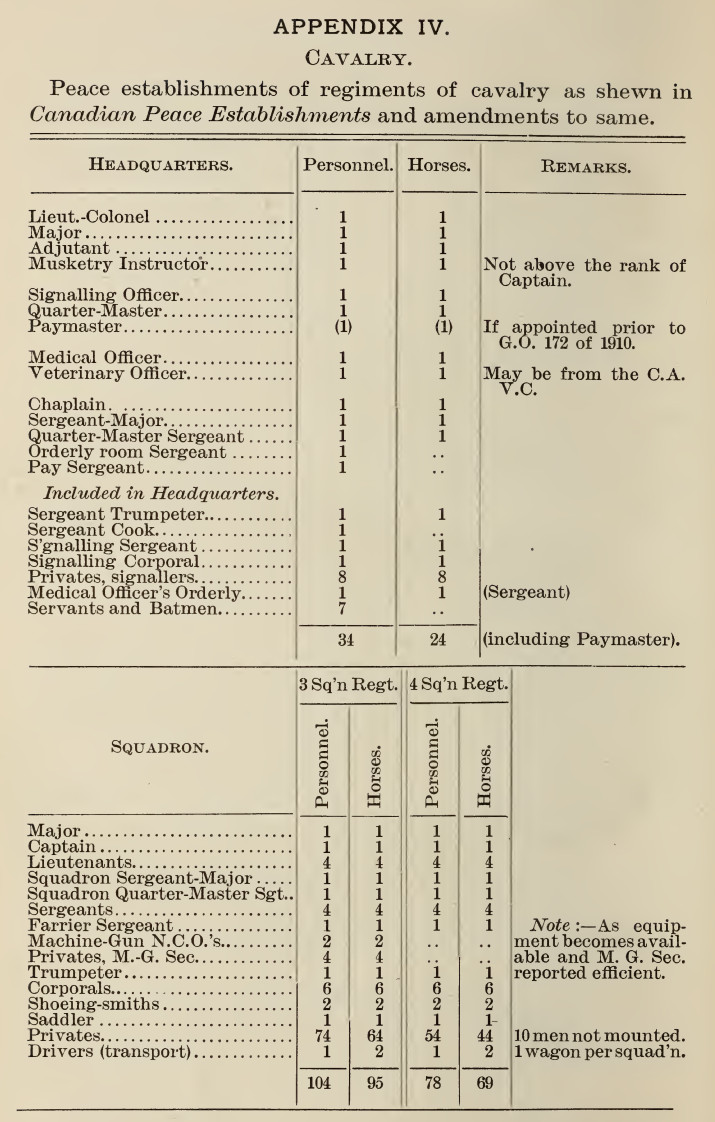

Headquarters

Headquarters

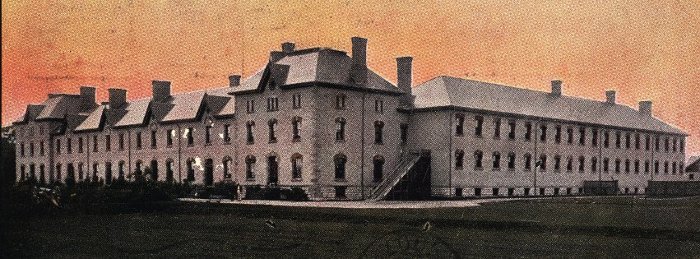

In 1867, there came to Canada, as the senior Staff Officer, a brilliant young soldier who, though but 34 years of age, had already seen service in the Crimea, at the Relief of Lucknow and in China, and who, in 1870, was chosen by Ottawa to command the Red River Expedition to the then almost unknown Canadian West, where the rebel Louis Riel headed an uprising to establish a Republic of North-West Canada.

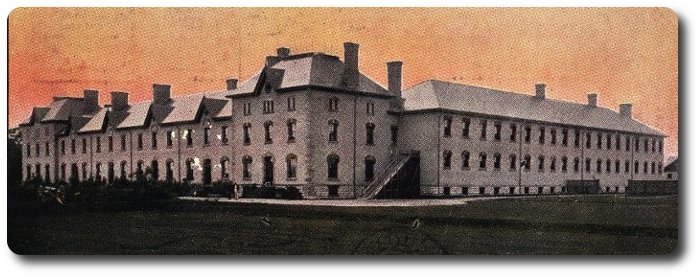

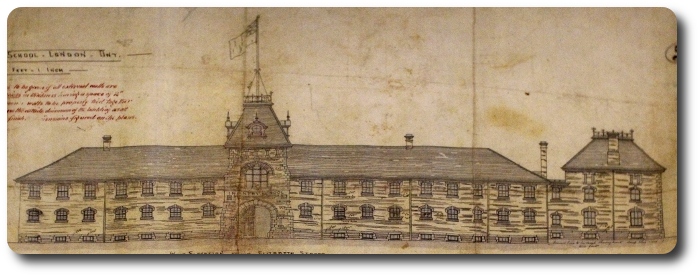

In 1867, there came to Canada, as the senior Staff Officer, a brilliant young soldier who, though but 34 years of age, had already seen service in the Crimea, at the Relief of Lucknow and in China, and who, in 1870, was chosen by Ottawa to command the Red River Expedition to the then almost unknown Canadian West, where the rebel Louis Riel headed an uprising to establish a Republic of North-West Canada. The School was formerly opened on the 31st March, 1888, with Colonel Henry Smith, a veteran of the North-West Rebellion of 1885, as Commandant, and the barracks became headquarters of "D" Company, Royal Infantry (sic). The establishment of the School was six Officers and one hundred N.C.O.'s and men, many of whom were recruited locally; and then started the first courses of instruction.

The School was formerly opened on the 31st March, 1888, with Colonel Henry Smith, a veteran of the North-West Rebellion of 1885, as Commandant, and the barracks became headquarters of "D" Company, Royal Infantry (sic). The establishment of the School was six Officers and one hundred N.C.O.'s and men, many of whom were recruited locally; and then started the first courses of instruction.

Washington, Sept. 20.—The General Staff of the army is hard at work on the new manuals for the sabre and the bayonet for the army. Hitherto these manuals have called for much skill on the part of enlisted men, so much, indeed, that few of them can acquire the art of wielding either weapon in a satisfactory manner. It is proposed to omit from the manuals everything of a fancy fencing character, such as is taught in the private drillrooms. It is intended that there shall be a return to the simplest methods, and that everything shall be on the most practical and useful basis. Both weapons are meant for use in time of war, and especially is this so of the bayonet. The officers who have been on duty in Manchuria with the Russian and Japanese armies are furnishing special reports to the General Staff on the subject, and such experts as Captain Herman J. Koehler, the master of the sword at the Military Academy, and Civil Engineer Cunningham, of the navy, who is an expert swordsman, and who had charge of the Naval Academy fencing last year, are also giving valuable advice along the line indicated. The War Department recently adopted a new type of sabre, which will be kept with a sharpened edge and carried in a wooden scabbard. A new bayonet was adopted several weeks ago, based on the results of the observations of our military attaches with the troops in Manchuria. The sabre and bayonet are therefore of fighting value, and the manual will be of a kindred practical spirit.

Washington, Sept. 20.—The General Staff of the army is hard at work on the new manuals for the sabre and the bayonet for the army. Hitherto these manuals have called for much skill on the part of enlisted men, so much, indeed, that few of them can acquire the art of wielding either weapon in a satisfactory manner. It is proposed to omit from the manuals everything of a fancy fencing character, such as is taught in the private drillrooms. It is intended that there shall be a return to the simplest methods, and that everything shall be on the most practical and useful basis. Both weapons are meant for use in time of war, and especially is this so of the bayonet. The officers who have been on duty in Manchuria with the Russian and Japanese armies are furnishing special reports to the General Staff on the subject, and such experts as Captain Herman J. Koehler, the master of the sword at the Military Academy, and Civil Engineer Cunningham, of the navy, who is an expert swordsman, and who had charge of the Naval Academy fencing last year, are also giving valuable advice along the line indicated. The War Department recently adopted a new type of sabre, which will be kept with a sharpened edge and carried in a wooden scabbard. A new bayonet was adopted several weeks ago, based on the results of the observations of our military attaches with the troops in Manchuria. The sabre and bayonet are therefore of fighting value, and the manual will be of a kindred practical spirit.