Topic: Halifax

Withdrawal of British Garrisons

Deseret Evening News, Salt Lake City, Utah, 19 April 1905

By: Truman L. Elton

It is by no means likely, even after the departure of the regulars, that Halifax will be bereft of its title of the Garrison City. … Still, the regulars will be missed sadly. The social atmosphere of Halifax will be visibly disturbed. Many of the most famous regiments of the British Army have been stationed there, and at no time since its inception has the garrison been without a liberal infusion of the best blood in the empire. This has furnished the town with much social capital, and its removal will be a social hardship.

The theory that Great Britain has only now made up her mind to accept unqualifiedly the American definition of the Monroe doctrine cannot be regarded as absolutely untenable. If it is the American contention—and it seems to be—that any spot on the continent now occupied by a foreign power cannot be suffered to fall into the hands of any other alien trespasser it would be inexcusably extravagant, from an American standpoint, for Great Britain to maintain a costly system of protection for something that is already safeguarded. It is by no means improbable that the time has come when Great Britain can afford to take that view.

However that may be, it has been apparent for a long time that British garrisons in North America were more ornamental than useful, that the reasons for their maintenance were more sentimental than urgent. It has been a costly demonstration too. Neither of Great Britain's remaining southern continental holdings—British Guiana and British Honduras—is self sustaining. For aught that her American insular colonies have yielded her during the last half century Great Britain would have been better off without them. The annual revenues from the West Indian islands have been falling off appreciably. The garrisons have added nothing to the prosperity of the regions in which they were placed. Canada has shown no signs of retrogression since the withdrawal of the garrisons. For some time Halifax and Esquimalt have been the only stations in the north of America supplied troops from British headquarters. Even at these distant posts of the empire only a handful of troops has been considered necessary since the forming of the confederation into the Dominion. The last large regular force in British America was in 1870, when Lord Wolseley made the Red River expedition into the north-west provinces. Immediately after that was completed the fiat went forth that Canada must thenceforth depend upon her militia for standing defence. A few months later the last battalion of regulars was withdrawn, leaving only the 2,000 provided as the garrison of Halifax. This number has remained stationary ever since, the small garrison at Esquimalt, on the other side of the continent, making the complement. During the past year there have been stationed at Halifax only 1,800 men of all arms and at Esquimalt only 369.

It is by no means likely, even after the departure of the regulars, that Halifax will be bereft of its title of the Garrison City. It will still be the most important of the twelve Military Districts of the Dominion. The Wellington barracks, erected at great expense, will be taken over by the Dominion government and set apart as quarters for the colonial military organizations. Still, the regulars will be missed sadly. The social atmosphere of Halifax will be visibly disturbed. Many of the most famous regiments of the British Army have been stationed there, and at no time since its inception has the garrison been without a liberal infusion of the best blood in the empire. This has furnished the town with much social capital, and its removal will be a social hardship.

It is by no means likely, even after the departure of the regulars, that Halifax will be bereft of its title of the Garrison City. It will still be the most important of the twelve Military Districts of the Dominion. The Wellington barracks, erected at great expense, will be taken over by the Dominion government and set apart as quarters for the colonial military organizations. Still, the regulars will be missed sadly. The social atmosphere of Halifax will be visibly disturbed. Many of the most famous regiments of the British Army have been stationed there, and at no time since its inception has the garrison been without a liberal infusion of the best blood in the empire. This has furnished the town with much social capital, and its removal will be a social hardship.

Halifax dates from the earlier half of the eighteenth century. The Halifax Gazette, the oldest newspaper in British America, first appeared in 1752. The town was founded at least three years before that, and during the Revolutionary war it was made a strong military post by Cornwallis. The Duke of Kent, father of Queen Victoria, was commandant of the garrison in his younger days and supervised the construction of the fortifications which gave the post the reputation of being the strongest fortress in the new world. On account of its situation and natural advantages it has a harbor which is extremely valuable as a naval base. Here it was that Boscawen's fleet collected to convey Wolfe and his troops to the conquest of Quebec.

As the headquarters of the British North American and West Indian squadron Halifax has seldom been without the presence of ships of war. Admiralty House, in Gottingen street, has long been the residence of flag officers. The dockyard, the property of the government, extends for half a mile along the harbor front and contains all the appliances and conveniences for a first class naval station. Its dry dock is the equal of any other on the continent, having a length of 613 feet and a width of seventy feet at the bottom. The city is defended by eleven forts and batteries, one of which, the citadel crowning the hill on which Halifax is built, is reputed to be, after Quebec, the strongest fortification in North America. The city itself extends along the slope of a hill and covers in area three miles in length by one in width. Its present population is not far from 50,000.

The headquarters of the British Pacific squadron were at Esquimalt, a little seaport on Vancouver Island, four miles from the city of Victoria. It has a magnificent harbor capable of accommodating the largest ships afloat. The garrison has for some time been reduced to a nominal basis, and the few remaining regulars will not regret the opportunity to return to the tight little isle. Next to Halifax, St. George and Ireland island, in the Bermudas, had been the most important naval and military stations of Great Britain in the North Atlantic. That Bermuda has been considered an important strategical point in the defence of the empire is shown by the size of the garrison maintained there. Until recently 7,950 men were quartered at that station. Jamaica has had 1,018, besides the colored West Indian regiments recruited there, and Barbados and St. Lucia. The total forms a considerable proportion of the 60,000 and odd soldiers of all ranks with which British colonies all over the world are garrisoned.

St. George, twelve miles from Hamilton, Bermuda, has had a somewhat peculiar history. Some years ago it has assigned as its garrison a battalion of the Grenadier guards which had manifested a disposition to mutiny. These men were sent to Bermuda as a disciplinary measure, and the remedy was most effectual. More recently St. George was a place of detention for Boer prisoners.

Barbados, the most windward of the Windward group, is the headquarters of the British forces in the West Indies, the commanding officer residing there having the rank of major general. St. Lucia, the largest and most picturesque island of the Windward group, possesses one of the finest harbors in the West Indies. It is the second naval station of the empire in the Caribbean region and is also a coaling station. Much treasure has been expended on its fortifications.

Bahama islands were formerly the headquarters of a rather formidable British garrison, but it has been greatly reduced in the last decade and consists now of a sorry remnant whose chief duty it seems to be to afford amusement to the numerous winter guests from the United States at the hotels. There are about 700 islets in the group, which lies east of Florida, the gulf stream intervening. Only twenty-five of these coral formations are inhabited, and most of the residents are descendants of Tories who fled thither for safety during the American Revolution and remained. One of these islands was the first land sighted by Columbus on his earliest voyage of discovery. Whether it was San Salvador or Watling Island is still a matter of dispute, but no one has had the temerity to deny that it was one of the 700.

Trinidad is the largest of the British West Indies except Jamaica. It is the southernmost of the Windward group, but it is not classed with those islands. It is a crown colony, the affairs of state being administered by a governor, assisted by executive and legislative councils. Port of Spain, the capital, is one of the finest towns in the West Indies. The garrison has long been reduced to a minimum. Trinidad is one of Great Britain's few self supporting American colonies. Her revenue is about equal to her expenditure. This island also has the distinction of having been discovered by Columbus.

Just a few lines to let you know that I am still in the ring. I am writing this by candlelight in an old barn, sprawled out flat on the floor. No doubt you've heard of the Canadians good work on

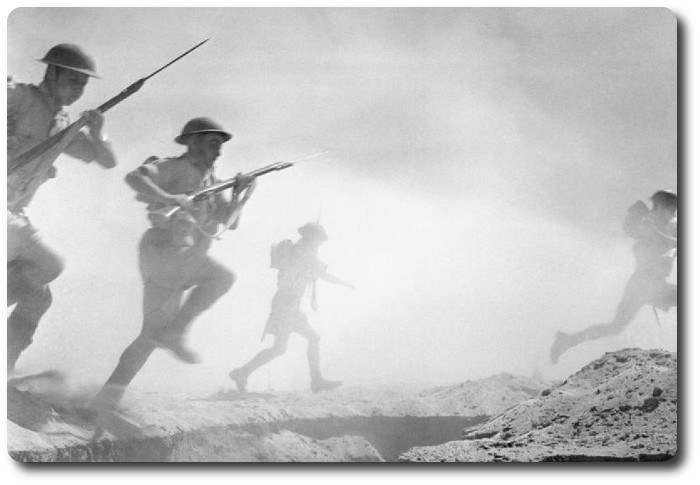

Just a few lines to let you know that I am still in the ring. I am writing this by candlelight in an old barn, sprawled out flat on the floor. No doubt you've heard of the Canadians good work on  We had two tanks with us (this was three days later) the most of the way, and for artillery fire—well, hell was let loose. It was terrible.

We had two tanks with us (this was three days later) the most of the way, and for artillery fire—well, hell was let loose. It was terrible.

If

If

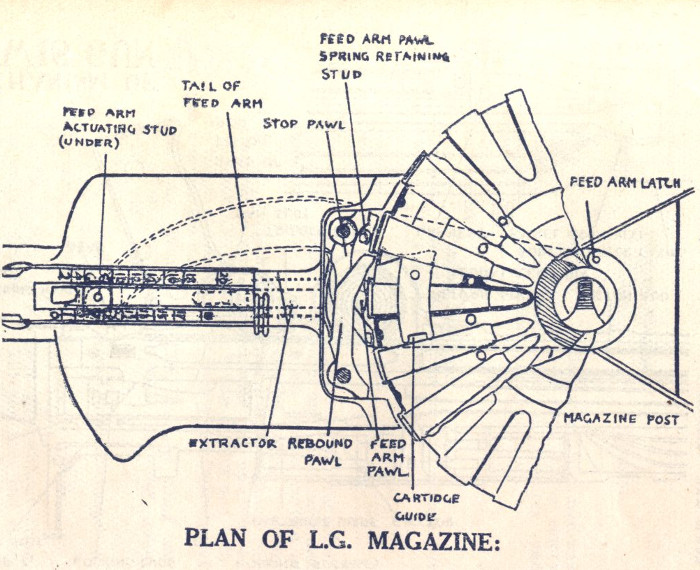

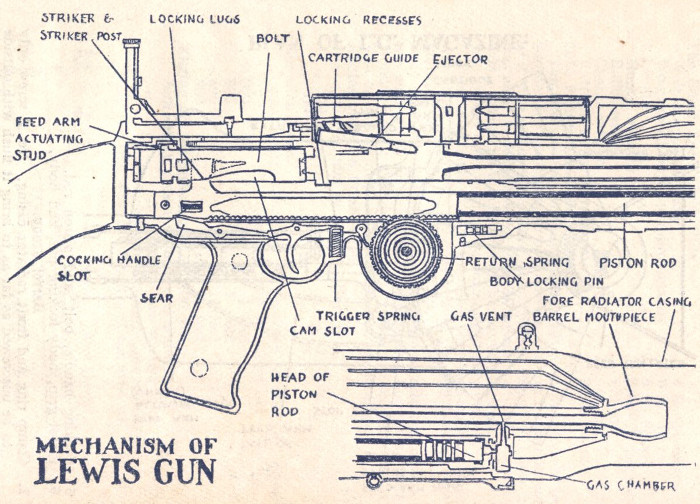

The machine guns which the Ontario Government will supply to the Canadian forces at the front at a cost of $200,000 might rather be termed rifles. The official name of the weapon is "

The machine guns which the Ontario Government will supply to the Canadian forces at the front at a cost of $200,000 might rather be termed rifles. The official name of the weapon is "

London, May 12.—A court-martial is in progress at Dublin against certain officers of the

London, May 12.—A court-martial is in progress at Dublin against certain officers of the  London, 13th February.—The whole absurd story of how the fashionable young bloods of the

London, 13th February.—The whole absurd story of how the fashionable young bloods of the  London, 22nd April.— In conformity with the instructions given by

London, 22nd April.— In conformity with the instructions given by

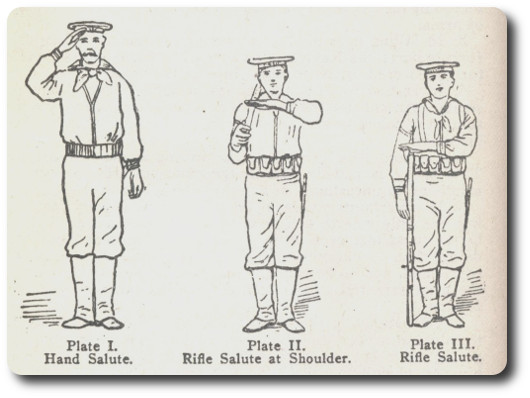

The Bluejacket's Manual, United States Navy, by Lieutenant Norman R. Van Der Veer, U.S. Navy, 1917

The Bluejacket's Manual, United States Navy, by Lieutenant Norman R. Van Der Veer, U.S. Navy, 1917

4. Cyclists will frequently be of use in assisting other troops to perform their protective duties, by their employment as standing patrols for instance (see Field Service Regulations, Part I, Sec 89.) or as a temporary relief for cavalry whilst the latter are withdrawn for purposes of watering, feeding, &c., or before they are sent out, or to act as a pivot round which cavalry can manoeuvre. At night their movements, owing to the silence in which they can be carried out, are difficult to detect. Formed bodies of cyclists should not carry out any independent movement at night beyond the protective line, owing to their greater vulnerability and liability to be thrown into confusion by an ambush or temporary obstacle during darkness than in daylight.

4. Cyclists will frequently be of use in assisting other troops to perform their protective duties, by their employment as standing patrols for instance (see Field Service Regulations, Part I, Sec 89.) or as a temporary relief for cavalry whilst the latter are withdrawn for purposes of watering, feeding, &c., or before they are sent out, or to act as a pivot round which cavalry can manoeuvre. At night their movements, owing to the silence in which they can be carried out, are difficult to detect. Formed bodies of cyclists should not carry out any independent movement at night beyond the protective line, owing to their greater vulnerability and liability to be thrown into confusion by an ambush or temporary obstacle during darkness than in daylight.

The modernization of armies is likely to take two forms, which are to some extent successive stages. The first is motorization; the second is true mechanization—the use of armoured fighting vehicles instead of unprotected men fighting on foot or horseback.

The modernization of armies is likely to take two forms, which are to some extent successive stages. The first is motorization; the second is true mechanization—the use of armoured fighting vehicles instead of unprotected men fighting on foot or horseback.

We carried enough firepower to act like a company. Six people—that's hard to believe, but we did. We had a small arsenal with us.

We carried enough firepower to act like a company. Six people—that's hard to believe, but we did. We had a small arsenal with us.

Ottawa, June 12. — Thirty-two years after the

Ottawa, June 12. — Thirty-two years after the