Topic: CEF

The Trenches of the Western Front

Trench Life; Canada's Part in the Present War; Empire Day, May 23rd, Ontario Department of Education, 1918

We never knew till now how muddy mud is,

We never knew how muddy mud could be.

– Trench Song

Trenches are like the suburbs in a great city. You are faintly conscious that people live in the next street, but you never see them. Your neighbours are as self-contained and silent as yourself. Sometimes their look-outs or machine-guns become loquacious; then you, too, grow conversational; and the whole line talks freely to the Germans two hundred yards away. It is only when your "stunt" in the front line is temporarily over, and you are marched back to billets, that you are able to cultivate your neighbour's exclusive society.

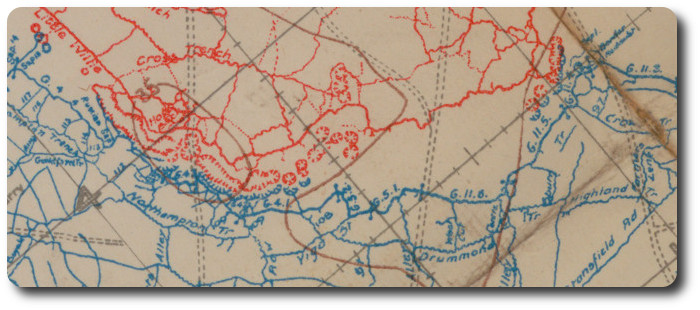

The front line or "fire" trench as it is called, is the nearest trench to the enemy. In front of the fire trench is a barbed wire entanglement. This barrier is slightly lower than the parapet of the trench, and is about ten feet in front of it; thus allowing sentries in the trenches to observe and fire over top of the wire. It is constructed by driving stakes firmly into the ground and twining the barbed wire about them in an intricate and criss-cross a manner as possible, so that it is a physical impossibility for soldiers to get through, unless the entanglement is first blown up by shell fire or cut with wire-cutters. This barrier is about twenty feet from front to rear, and extends in a practically unbroken line along both sides of the west front. German use iron stakes; the Allies, wood. Many a soldier, crawling about in the darkness, engaged in patrol work or bombing raids, owes his life to this; for, if he feels an iron post, he knows he is near a German trench, and withdraws as unobtrusively as possible.

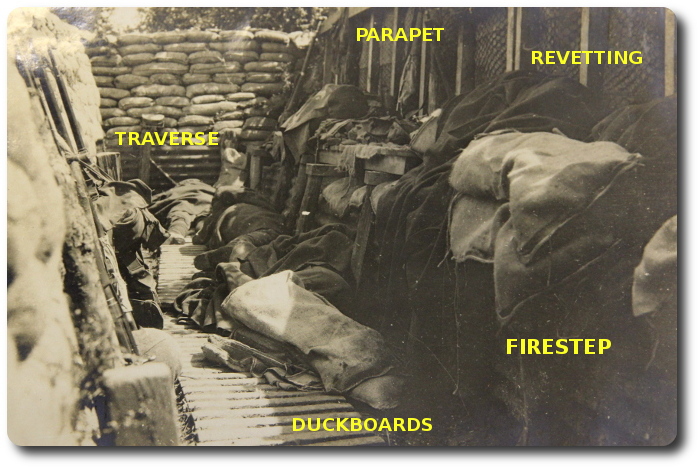

The fire trench is from six to eight feet deep, and is divided into "fire bays," the fire bay being the distance, about thirty feet, between "two traverses." The traverse is a barricade in the trench reinforced with sandbags and "revetted" with branches of trees or poultry netting, to keep the earth from slipping in wet weather. The traverse is to prevent enfilading fire. It a trench were to be built straightaway in a direct line, the Germans could sweep hundreds of yards of it with machine-gun fire. Again, if a shell should burst in a straight trench, it would wound or kill many men on its right and left. In a traversed trench, a shell can do damage only in the fire bay in which it lands; and Tommy is an expert at making a quick exit around the traverse on such an occasion.

The front wall of the trench is called the "parapet," the rear wall is called the "parados." The top of the front wall is reinforced with two to four layers of sandbags, covered with earth. Cleverly disguised loopholes for observation and sniping purposes are constructed in the parapet. Saps, or small narrow trenches, cleverly disguised, run under the barbed wire out into No Man's Land, and are known as "listening posts" or "bombing saps."

At the bottom of the front wall of the fire bay is constructed a heavy wooden platform about two feet wide and two and a half feet high, strongly reinforced underneath by sandbags. This platform is called the fire step and, by standing on it at night, soldiers can look over the top of the parapet, listening and observing for undue activities on the part of the Germans in No Man's Land. During an attack, the men can stand on the fire step and rest their rifles or mount machine-guns on the top of the parapet, and thus cover the advancing enemy.

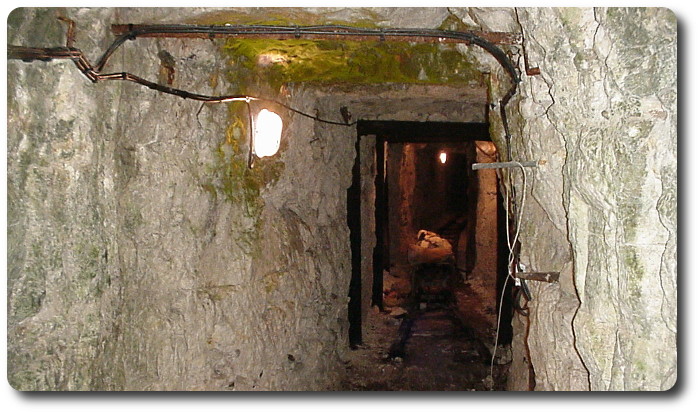

Dugouts and bomb stores with shell-proof covers are built into the wall of the trench—generally into the parados behind a traverse, so as to protect the entrance from shell fragments or enfilade fire.

Running back from the fire trench are the communication trenches. These are about three feet wide, and are built in zig-zag formation, to prevent their being raked by enemy fire. They are generally "one-way streets," that is, one trench is used for the entrance, another for the departure of troops. At intervals are built recesses, into which stretcher-bearers, ration-carriers, or others, may step, while troops movements are in progress.

In the rear of the front line, there suns a support trench, with barbed wire and fire steps like the front line. Here are kept various stores, such as food, ammunition, bombs, etc. From it reinforcements can be quickly supplied to the front line, and it forms a fort if the troops are forced out of the fire trench. Immediately in the rear of these trenches is generally a ruined village, where reserves are quartered in bomb-proof cellars, dug deep below the shattered houses.

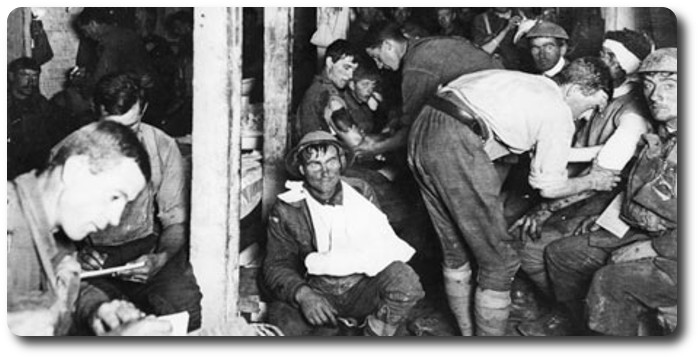

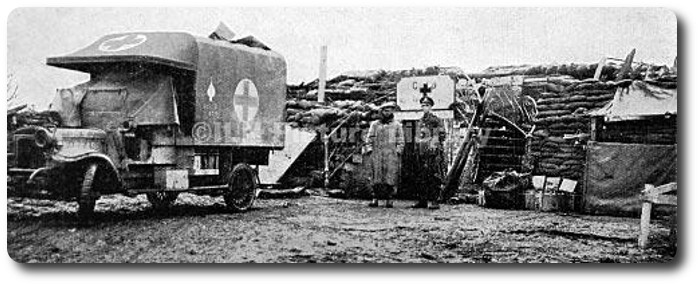

At a varying distance behind the trenches is usually to be found a road, with steep banks on each side, into which the communications trenches lead. In the banks are "elephant dugouts," twenty to forty feet deep. These are supported by steel girders, and each can comfortably accommodate from thirty to fifty men. They are often well-furnished and electrically lighted. Many German dugouts had carpet or linoleum on the floors, papered walls, easy chairs, pianos (looted, of course), and other indications that the occupants had come to stay. Reserve troops, dressing stations, and battalion headquarters occupy elephant dugouts. All communication trenches, dugouts, and roads are named, and while Tommy's nomenclature may disregard geography, it is rich in imagination. Hyde Park Row, Whitechapel, Hindenburg Alley, Yonge Street, Rosedale, may all be in the same sector. "My Little Gray Home in the West" is next-door to the Ritz-Carlton; a little farther along are "Vermin Villa," "Rat's Retreat," and "The Suicide Club." One wag hung on a dugout entrance this sign: "To let. All modern inconveniences, including gas and water."

Away behind the front are located the rest billets. "Rest" is in most respects a misnomer, because troops in billets have to drill, repair roads, dig trenches, act as carrying-in parties, and withal keep spotlessly clean and fit. This is essential, because the least slackening means inefficiency and mischief.

The quartermaster-sergeant marched along the communication trench and entered the firing line, says The London Chronicle.

The quartermaster-sergeant marched along the communication trench and entered the firing line, says The London Chronicle.

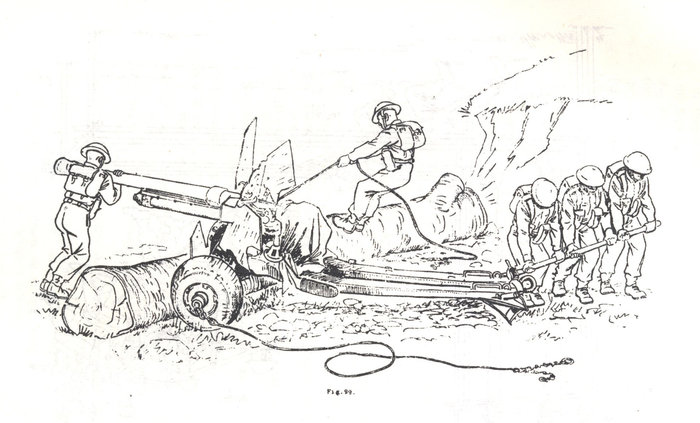

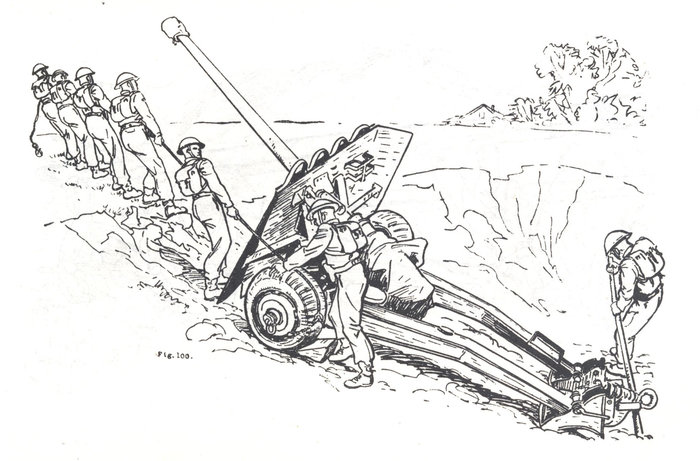

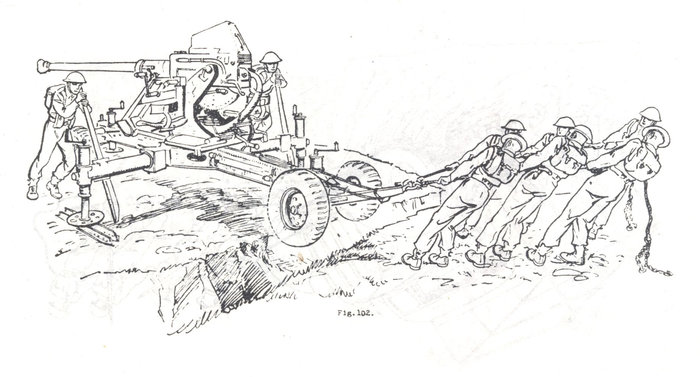

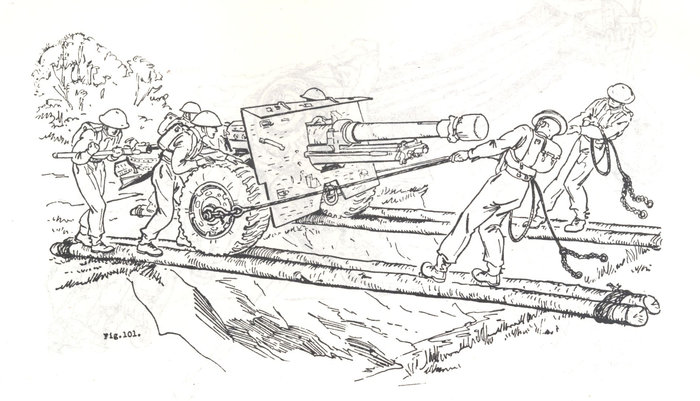

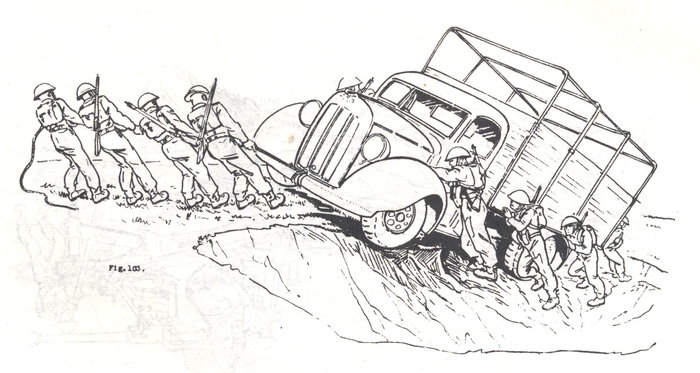

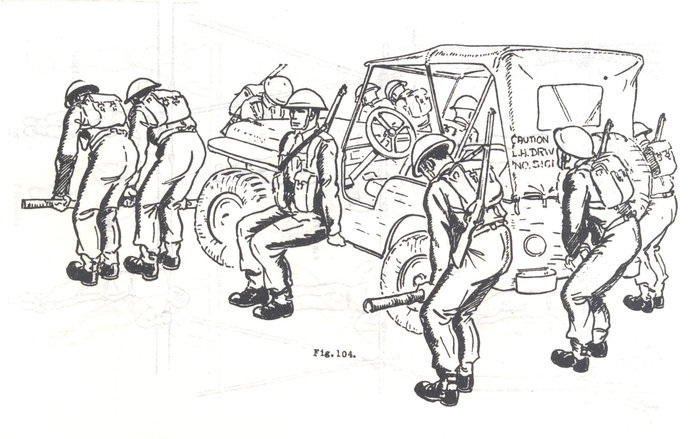

These images, contrary to looking like methods of recovery and cross-country mobility, are taken from the publication Basic and Battle Physical Training, Part III, Syllabus of Battle Physical Training and Battle Physical Efficiency Tests (1946). The diagrams show recommended physical training exercises using available vehicles and equipment to develop both strength training and teamwork.

These images, contrary to looking like methods of recovery and cross-country mobility, are taken from the publication Basic and Battle Physical Training, Part III, Syllabus of Battle Physical Training and Battle Physical Efficiency Tests (1946). The diagrams show recommended physical training exercises using available vehicles and equipment to develop both strength training and teamwork.

It is June 1900, and the First Provisional Battalion is in Kroonstad, Orange Free State. It is composed of men who have been left behind because of illness or wounds. Eventually the battalion will catch up with the main body and the men will rejoin their regiments. No. 5 Company is composed of 17 members of

It is June 1900, and the First Provisional Battalion is in Kroonstad, Orange Free State. It is composed of men who have been left behind because of illness or wounds. Eventually the battalion will catch up with the main body and the men will rejoin their regiments. No. 5 Company is composed of 17 members of

The

The

One of our most agreeable duties [at the

One of our most agreeable duties [at the

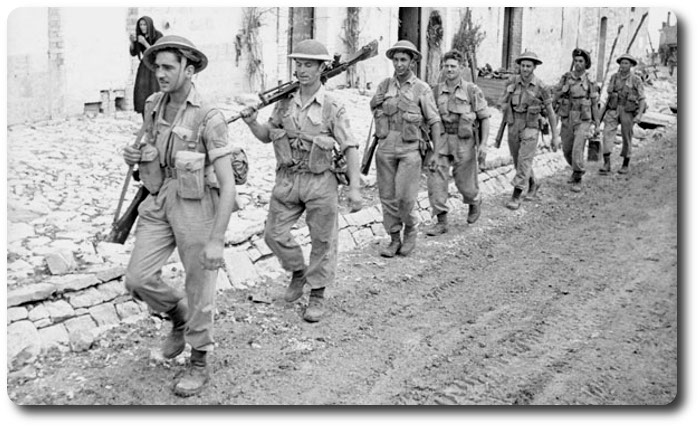

The Canadians—many of them—salute only when necessary. They look upon this form of exercise as an inconvenience and unnecessary except when they meet their own officers. But, as in many other things, they are quickly learning to do the proper thing—to pay respect to the rank. British officers are sticklers for etiquette, consequently the British rankers are always very proper.

The Canadians—many of them—salute only when necessary. They look upon this form of exercise as an inconvenience and unnecessary except when they meet their own officers. But, as in many other things, they are quickly learning to do the proper thing—to pay respect to the rank. British officers are sticklers for etiquette, consequently the British rankers are always very proper.

The Bluejacket's Manual, United States Navy, by Lieutenant Norman R. Van Der Veer, U.S. Navy, 1917

The Bluejacket's Manual, United States Navy, by Lieutenant Norman R. Van Der Veer, U.S. Navy, 1917

The Montpelier, Idaho, infantryman said later, "I felt something hit me on the arm. I thought it was the squad leader jabbing me.

The Montpelier, Idaho, infantryman said later, "I felt something hit me on the arm. I thought it was the squad leader jabbing me. The interdependence of men, especially in jungle warfare, has wrought what one officer called a revolutionary change in race relations in the military. Vietnam is the first war in which all U.S. units are thoroughly integrated.

The interdependence of men, especially in jungle warfare, has wrought what one officer called a revolutionary change in race relations in the military. Vietnam is the first war in which all U.S. units are thoroughly integrated. Earlier in the war, a U.S. 101st Airborne company was commanded by a Negro captain from Atlanta, Ga. The captain was articulate, well;-educated and very much the commander of his men.

Earlier in the war, a U.S. 101st Airborne company was commanded by a Negro captain from Atlanta, Ga. The captain was articulate, well;-educated and very much the commander of his men.

A day after he should have left Khe Sanh, the sergeant finally got his orders. His friends congratulated him. Home, today he was starting home.

A day after he should have left Khe Sanh, the sergeant finally got his orders. His friends congratulated him. Home, today he was starting home. A few hours later a Marine CH46 helicopter began spiraling down with a full load of replacements, men just starting their Vietnam tour.

A few hours later a Marine CH46 helicopter began spiraling down with a full load of replacements, men just starting their Vietnam tour.

London, November 4.—Canadian engineers have discovered at

London, November 4.—Canadian engineers have discovered at  The project began a year ago as a side-line to the

The project began a year ago as a side-line to the