Topic: The Field of Battle

Vietnam Sketchbook (Part 2)

War's Something More than Charts, Headlines

There's more. Much more, to the war in Vietnam than battle reports and casualty figures, statistics and strategy. Above all, there are the soldiers, the "GI Joes," each fighting for his life in a very personal way, in his own personal war. John Wheeler, who has been covering Vietnam for The Associated Press for years, recounts some of those personal experiences, funny and bitter, tragic and ironic, that make up the war in Vietnam.

Eugene Register-Guard, 18 August 1968

By John T. Wheeler, of Associated Press

For all the horror of war, there is still humor.

A reconnaissance team sat in its Army helicopter as it dived toward a landing zone deep in enemy territory. As the chopper leveled out, the door gunner panicked and pushed the first heavily laden recon man out while the chopper was still 25 feet in the air.

As the chopper dropped lower, the next man paused at the door, got a firm grip on the door gunner's arm and dragged him out when he jumped.

The door gunner, without adequate field gear, spent the next five days with the recon team. When the patrol was over, all the recon men were decorated. The door gunner got an official reprimand.

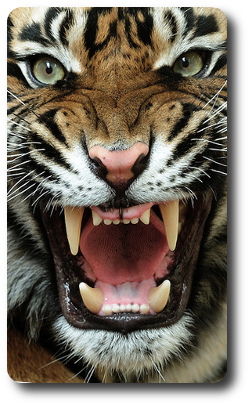

For a man on night ambush, there are many perils. Cpl. Jim Shepherd didn't know it that night, but he had one standing right beside him.

The Montpelier, Idaho, infantryman said later, "I felt something hit me on the arm. I thought it was the squad leader jabbing me.

The Montpelier, Idaho, infantryman said later, "I felt something hit me on the arm. I thought it was the squad leader jabbing me.

Shepherd turned and faced not his squad leader but a grown tiger. The tiger, apparently satisfied that the 19-year-old corporal would make a satisfactory dinner, began dragging Shepherd away.

Shepherd pounded the tiger's face with his free right hand. He was afraid to try and jerk free for fear of losing his left arm. His buddies were afraid to shoot for fear of hitting him.

"He got me into the water and I guess he figured he couldn't get me across the creek. He probably didn't know what to do with me," Shepherd said.

What the tiger did do was drop Shepherd in the water and move majestically into the night in search of slightly smaller prey. Shepherd went to hospital for stitched and two weeks of antirabies shots.

The interdependence of men, especially in jungle warfare, has wrought what one officer called a revolutionary change in race relations in the military. Vietnam is the first war in which all U.S. units are thoroughly integrated.

The interdependence of men, especially in jungle warfare, has wrought what one officer called a revolutionary change in race relations in the military. Vietnam is the first war in which all U.S. units are thoroughly integrated.

A 25th Division battalion commander once said, "There is no room for bigotry in foxholes." The comment was made after a particularly bitter battle in "Hell's Half Acre" near the division's headquarters at Cu Chi.

During the fight, one U.S. squad was being systematically shot to pieces by Viet Cong snipers. Four bodies of white GIs lay deep in the snipers' kill zone. A powerfully built sergeant called out for volunteers to race out and pull the bodies and weapons in.

Spec. 4 Newman heard the call in the bottom of a trench where he was resting a hip wound. The Baltimore, Md., Negro was under no military compulsion to volunteer. There were enough unwounded men to do the job. But he scrambled painfully out of the trench and began running with a heavy limp into the kill zone.

The wound slowed him down. Everybody made it to protection in shell holes but Newman, whose side was opened up by a burst of enemy automatic weapons fire. Two men immediately leaped from the trench to rescue Newman. One was white, the other Negro.

Earlier in the war, a U.S. 101st Airborne company was commanded by a Negro captain from Atlanta, Ga. The captain was articulate, well;-educated and very much the commander of his men.

Earlier in the war, a U.S. 101st Airborne company was commanded by a Negro captain from Atlanta, Ga. The captain was articulate, well;-educated and very much the commander of his men.

The company's first sergeant was the product of the Mississippi Delta, a white with little formal schooling.

The captain and the sergeant worked together in near perfect teamwork with frequent gusts of humor.

The battalion commander said that more of the company's men undoubtedly returned home alive that they would have if the relationship had been any different.

If race had been elbowed out of the foxholes, at least one chaplain says that the long-held belief that atheists are also absent is not true.

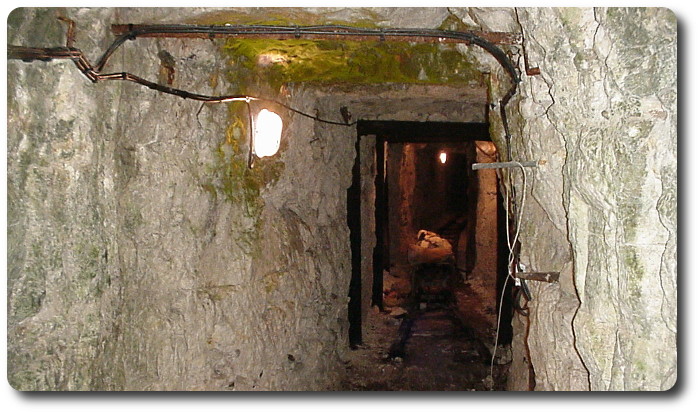

The chaplain, Navy Lt. Ray Stubble of Milwaukee, Wis., ministered to the 26th Marine Regiment during the worst days of the siege at Khe Sanh south of the DMZ.

Sitting in a bunker during one shelling, Stubbie said the proportion of atheists in foxholes and trenches was about the same as on any peaceful street in America.

What about the old saying, then, "There are no atheists in foxholes?"

"Maybe it was true once, but it isn't now. Perhaps the world has changed. I don't know. But the shelling isn't bringing in any more men for religious purposes," he said.

A day after he should have left Khe Sanh, the sergeant finally got his orders. His friends congratulated him. Home, today he was starting home.

A day after he should have left Khe Sanh, the sergeant finally got his orders. His friends congratulated him. Home, today he was starting home. A few hours later a Marine CH46 helicopter began spiraling down with a full load of replacements, men just starting their Vietnam tour.

A few hours later a Marine CH46 helicopter began spiraling down with a full load of replacements, men just starting their Vietnam tour.

London, November 4.—Canadian engineers have discovered at

London, November 4.—Canadian engineers have discovered at  The project began a year ago as a side-line to the

The project began a year ago as a side-line to the

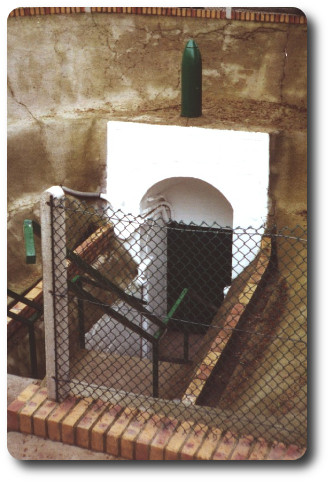

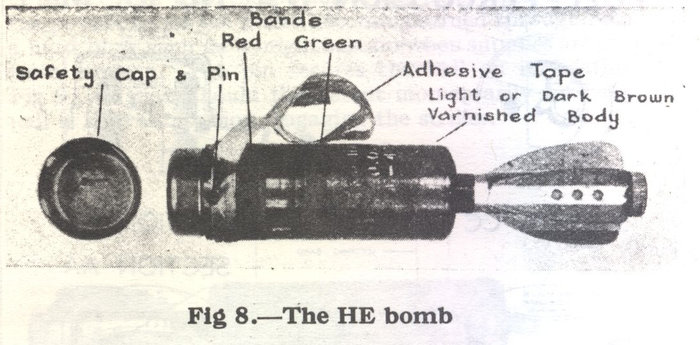

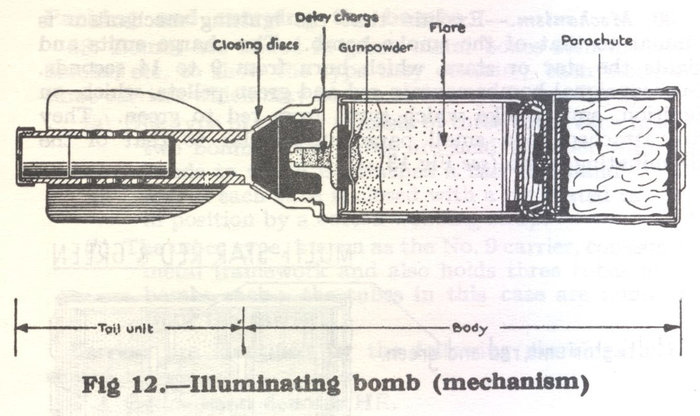

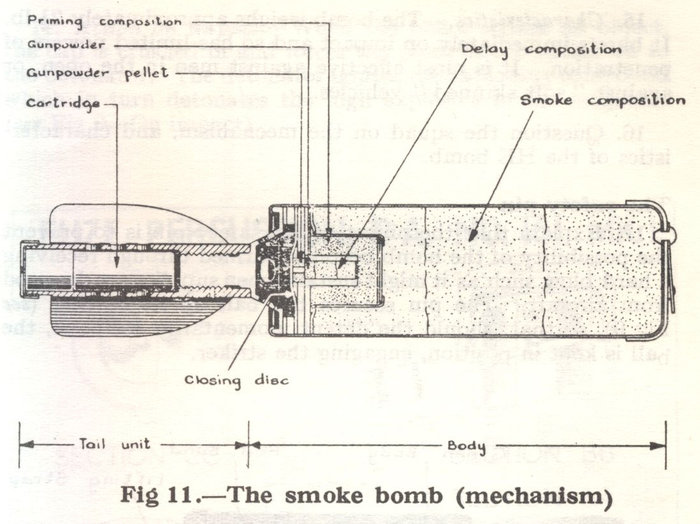

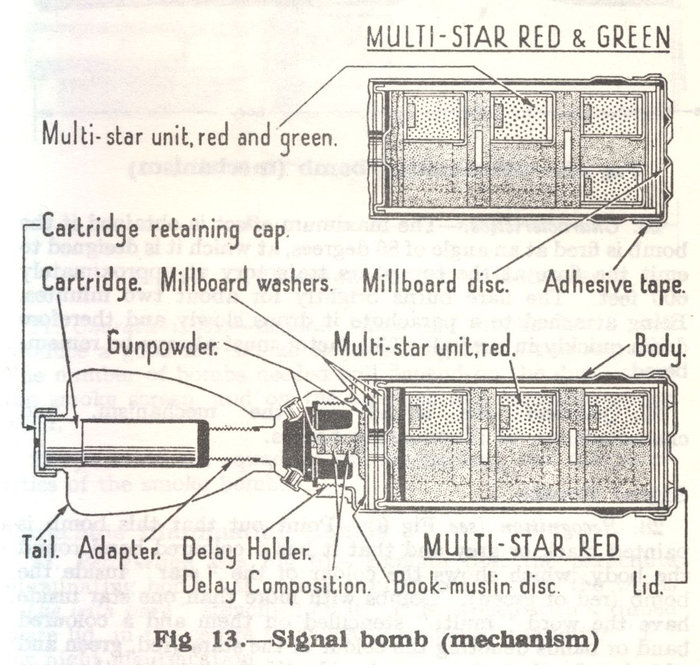

2-inch Mortar Ammunition (1949)

2-inch Mortar Ammunition (1949)

"Let me briefly tell you how the day is passed. Early in the morning, generally at half-past four, there is a scraping at the tent door, and a voice is heard, "Signoir alzate, vi prego, in cafe a pronto," to which a lisping voice responds, "What Thpero, it ith'nt five, thurely?'…'Si, signoir, vbicino a'le cinque,' cries the faithful old idiot (our best servants have been in lunatic asylums), and the British officer is soon up and doing, his coffee is drunk, biscuit and pork are consumed, a wallet is thrown across the shoulder, containing provender for the day, and a flask of rum; the sword is girt on, and away goes out companion to the trenches, there to remain until 6 p.m., leaving us to snooze away until the sun has afforded us a cheering supply of light and heat, when we rise from our bed of blankets, and, having drunk in pure air during the night, rush to breakfast with ravenous appetites.

"Let me briefly tell you how the day is passed. Early in the morning, generally at half-past four, there is a scraping at the tent door, and a voice is heard, "Signoir alzate, vi prego, in cafe a pronto," to which a lisping voice responds, "What Thpero, it ith'nt five, thurely?'…'Si, signoir, vbicino a'le cinque,' cries the faithful old idiot (our best servants have been in lunatic asylums), and the British officer is soon up and doing, his coffee is drunk, biscuit and pork are consumed, a wallet is thrown across the shoulder, containing provender for the day, and a flask of rum; the sword is girt on, and away goes out companion to the trenches, there to remain until 6 p.m., leaving us to snooze away until the sun has afforded us a cheering supply of light and heat, when we rise from our bed of blankets, and, having drunk in pure air during the night, rush to breakfast with ravenous appetites.

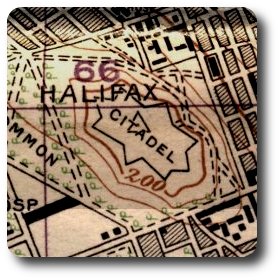

It is by no means likely, even after the departure of the regulars, that Halifax will be bereft of its title of the Garrison City. It will still be the most important of the twelve Military Districts of the Dominion. The

It is by no means likely, even after the departure of the regulars, that Halifax will be bereft of its title of the Garrison City. It will still be the most important of the twelve Military Districts of the Dominion. The

Just a few lines to let you know that I am still in the ring. I am writing this by candlelight in an old barn, sprawled out flat on the floor. No doubt you've heard of the Canadians good work on

Just a few lines to let you know that I am still in the ring. I am writing this by candlelight in an old barn, sprawled out flat on the floor. No doubt you've heard of the Canadians good work on  We had two tanks with us (this was three days later) the most of the way, and for artillery fire—well, hell was let loose. It was terrible.

We had two tanks with us (this was three days later) the most of the way, and for artillery fire—well, hell was let loose. It was terrible.

If

If

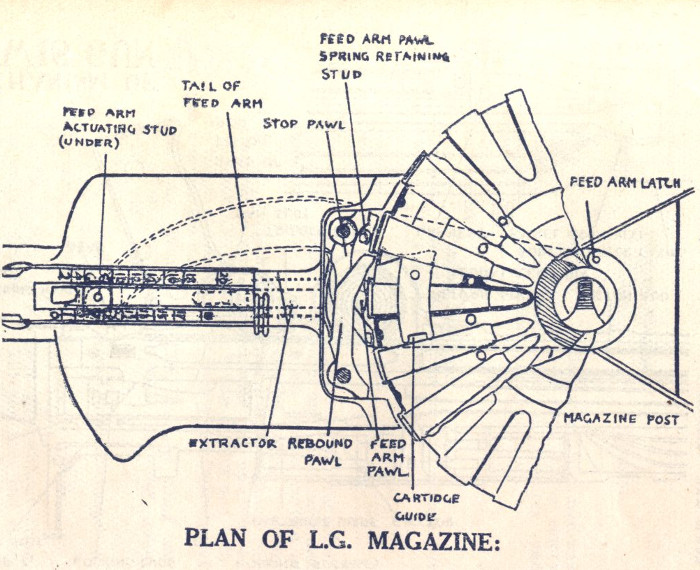

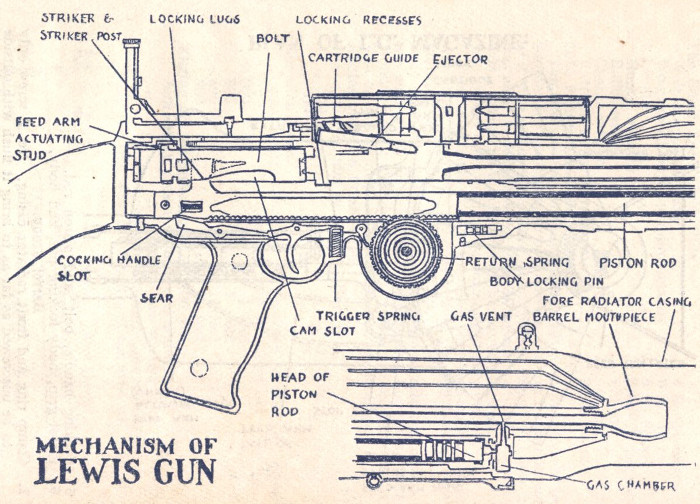

The machine guns which the Ontario Government will supply to the Canadian forces at the front at a cost of $200,000 might rather be termed rifles. The official name of the weapon is "

The machine guns which the Ontario Government will supply to the Canadian forces at the front at a cost of $200,000 might rather be termed rifles. The official name of the weapon is "

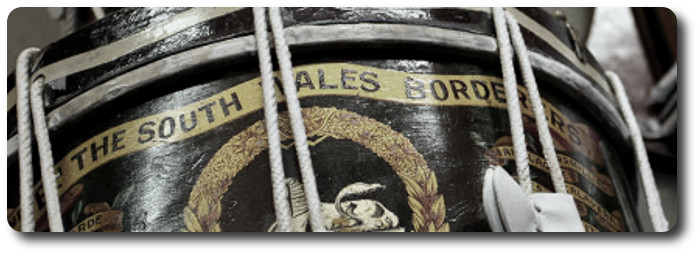

London, May 12.—A court-martial is in progress at Dublin against certain officers of the

London, May 12.—A court-martial is in progress at Dublin against certain officers of the  London, 13th February.—The whole absurd story of how the fashionable young bloods of the

London, 13th February.—The whole absurd story of how the fashionable young bloods of the  London, 22nd April.— In conformity with the instructions given by

London, 22nd April.— In conformity with the instructions given by

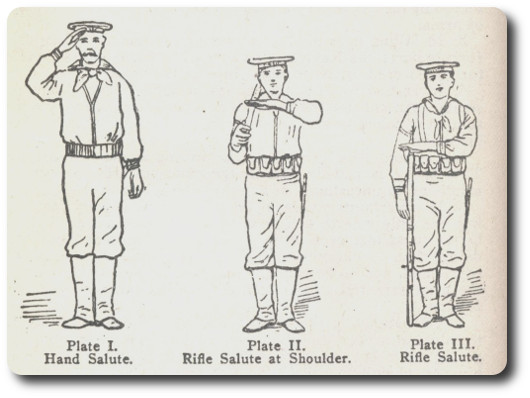

The Bluejacket's Manual, United States Navy, by Lieutenant Norman R. Van Der Veer, U.S. Navy, 1917

The Bluejacket's Manual, United States Navy, by Lieutenant Norman R. Van Der Veer, U.S. Navy, 1917

4. Cyclists will frequently be of use in assisting other troops to perform their protective duties, by their employment as standing patrols for instance (see Field Service Regulations, Part I, Sec 89.) or as a temporary relief for cavalry whilst the latter are withdrawn for purposes of watering, feeding, &c., or before they are sent out, or to act as a pivot round which cavalry can manoeuvre. At night their movements, owing to the silence in which they can be carried out, are difficult to detect. Formed bodies of cyclists should not carry out any independent movement at night beyond the protective line, owing to their greater vulnerability and liability to be thrown into confusion by an ambush or temporary obstacle during darkness than in daylight.

4. Cyclists will frequently be of use in assisting other troops to perform their protective duties, by their employment as standing patrols for instance (see Field Service Regulations, Part I, Sec 89.) or as a temporary relief for cavalry whilst the latter are withdrawn for purposes of watering, feeding, &c., or before they are sent out, or to act as a pivot round which cavalry can manoeuvre. At night their movements, owing to the silence in which they can be carried out, are difficult to detect. Formed bodies of cyclists should not carry out any independent movement at night beyond the protective line, owing to their greater vulnerability and liability to be thrown into confusion by an ambush or temporary obstacle during darkness than in daylight.

The modernization of armies is likely to take two forms, which are to some extent successive stages. The first is motorization; the second is true mechanization—the use of armoured fighting vehicles instead of unprotected men fighting on foot or horseback.

The modernization of armies is likely to take two forms, which are to some extent successive stages. The first is motorization; the second is true mechanization—the use of armoured fighting vehicles instead of unprotected men fighting on foot or horseback.

We carried enough firepower to act like a company. Six people—that's hard to believe, but we did. We had a small arsenal with us.

We carried enough firepower to act like a company. Six people—that's hard to believe, but we did. We had a small arsenal with us.