Topic: Army Rations

Feeding Soldiers on the Firing Line

I heard an officer just back from a week's riot in London, where he had lived at the Savoy and Romano's, exclaim with undoubted sincerity, as his batman set the familiar trench dish before him once more: "Good old bully beef! It tastes like real food after the fussy stuff back in civilization.

Britton B. Cooke, in The Toronto Globe

Fort Frances Times, 27 January, 1916

Anyone returning from the front finds innumerable questions leaping at him from the lips of his friends who have not been there. Soldiers still in training in Canada want to know such things as whether the Sam Brown or the Web equipment is used at the front. Civilians who follow the war summaries closely want to be told just how many men there are behind our lines, and how the wire entanglements are laid out, and what is wrong or isn't wrong with the Ross rifle. Youngsters want to know what a shell looks like when it is bursting under one's nose, or some question equally difficult to answer, and young women inquire as to the whereabouts of "A" Regiment or "B" Regiment, or such-and-such an artillery brigade. But older women, when all the others have fired their questions and been disappointed in their answers, have just one question to ask. They wait, as a rule, until no-one else seems to be within ear-shot, and then ask: "Have you enough to eat? Have they plenty to eat? What should one send them to eat? What sort of horrid plum pudding will they give my Tom, do you suppose? — Oh, dear me, are you sure they're not hungry? Or if they want anything to eat — between meals? Or if they should get hungry in the night—or—?"

Men Are Well Fed

If all questions sprang from such deep, kindly affection and if they could all be answered as happily as these, the war itself would soon be over. The men at the front are so well fed that their families will have to improve the standard of living when they come home—most of them at all events. They may be wet very often—though conditions this winter are much better than last winter—and they may miss the dire operation of carving the turkey at home and satisfying the hysterical appetites of small persons with round eyes close down near the table cloth, but the army in France and Flanders uses the same calendar as the people at home do, and attached the same importance to the 25th of December as others. In London when I left in October there were hundreds of women in the indirect employ of the War Office commissariat making special puddings for Christmas in the trenches. This same Christmas dawn that sets the birds chattering under the eaves of Canadian houses and sets the hardy songsters of northern France fluttering out from under the thatches on French and Belgium straw stacks behind our lines saw military cooks, like domestic cooks, making special preparations for the day.

A Top-Hole Day

"Christmas!" exclaimed one of those always merry young subalterns that occur every here and there among the men, something like the almonds in the cake. "Why, last Christmas was just about as jolly a Christmas as I ever had. We had a top-hole day." He was English, of course. "And except that—well, one didn't have one's folks with one—except fopr that it was a bully sort of a day. We were in a pretty bad country just then, not nearly so good as this, and the roofs of the dug-outs leaked because we hadn't got onto the corrugated iron stunts for a roof. But we had a feast, and some games—and potted at a few Boches in between whiles.

You never can believe all these subalterns tell you, especially if they have only got one "pip" instead of two on their cuffs. For the difference between one "pip" and two is more than just the difference between a first and second lieutenant. It is the difference between responsible and irresponsible authority. In this case, however, the truth was not deeply disguised. There may be homesickness buried under nonsense, but at least there is a meal of meals on the day when nobody is supposed to lack happiness.

Getting Food to the Front

The getting of the food to the men on the firing line is the only real difficulty of this branch of the service. Last night if one had been in some high place looking down over the line of battle one might have seen little parties being formed at regular intervals along the line of trenches. Each party, lined up first with its back to the rear wall of the trench, numbered in subdued tones, and then marched off under the command of a non-commissioned officer or a subaltern toward the rear. One might, in one's imagination at all events, have seen those hundreds of little parties stealing back through hundreds of long, tortuous communications trenches, emerging finally from behind a bit of cover—a hedge or a low hill or ruined building—on the road leading back toward brigade headquarters. Shells dropped in this vicinity occasionally, because the enemy probably knows it is a very important part of our line of supply; rifle bullets go whinging by every now and then, or a machine gun from the German side is spraying the vicinity. Here the ration party connects with the detail that has brought the food supply from the local depot. With quick movements the load is taken up by the front line party, and they drop back into the trench with beef and pork, bread and potatoes, salt, and all the odds and ends of provisions. As one party returns so hundred all along the front have been returning. Some have had a casualty or two. Some even more than that. But the food gets back ultimately, and is parcelled out, platoon by platoon, bay by bay. There will be no cooking done now at night, but bye-and-bye, when the light begins to show over the German parapet across the way and the sentries stand down for the day, you may imagine you see countless small spirals of smoke curling up from the trenches and the jewel-like glow of countless small fires perched precariously in home-made braziers at various points along the trench wall. Over each fire hangs a smoke-blackened, crescent-shaped saucepan (the mess tin), and in the quiet glow of the brazier you may make out the face of the man who is tending it. He probably has a long spoon or a jack-knife or a real fork wherewith he gravely stirs the contents of the tin. The smoke from the brazier licks up around the sides of the saucepan occasionally and takes a sort of taste of the contents, leaving its flavor therein. But what is a bit of smoke in a trench stew? If you are not careful the spoon or other weapon with which you stir the mess may become a bit gummy and encrusted with the deposits of many stirrings, but the flavor, even then, is excellent. I heard an officer just back from a week's riot in London, where he had lived at the Savoy and Romano's, exclaim with undoubted sincerity, as his batman set the familiar trench dish before him once more: "Good old bully beef! It tastes like real food after the fussy stuff back in civilization. I pretty nearly asked for it on the steamer train coming from Victoria Station."

Daytime is Resting Time

Except when an advance is being prepared, or is expected from the other side of No Man's Land, daytime is the resting time of the men, or if they have had enough sleep, it affords then unlimited scope for the practice of mending, shaving, cleaning one's rifle, or cooking. From Stand-down at dawn till Stand-to at dusk there is always somebody cooking something in the trenches. It is not only a pastime, but it is a subject for infinite research work. In one trench I heard of a man, a six-footer with a beard, who in other days used to do plumbing in Toronto, who had become so immersed, not to say buried, in the mysteries of cookery that his dishes, albeit limited in number, were in great demand. He had learned to make a sort of chop suey seasoned with a strange herb discovered in what used to be Anton's (Antoine's) farm.

That concerns the feeding of the men in the trenches. They are their own cooks for only a limited number of days while living in the front line. When, however, they get their relief and are sent back first to the reserve line and then go to the billets, they are served by real cooks from real kitchens and have a chance to wash the grime off their hands if they want to. Also there is more water to drink than in the front line, where there is a drinking supply fairly convenient and under cover. But the problem of feeding the biggest family in the world, except the Russian Czar's family of fighting men, is not solved merelkyu by the ration parties and the stew-tenders either in the trenches or in billets.

Some Sunday in London take a twenty-four bus down Oxford street past the Bank and down Commercial road to, say, the East India Docks. While all the rest of London is warming itself at its grate fires or sipping tea, down here a beef boat from Uruguay or the Argentine is working her way into the still waters of the dock, through the narrow gate that cuts off the open River Thames, with its constant rise and fall, from the docks proper. There are already seven other ships in the dock, not counting insignificant little trawlers and wind-jammers. These seven black-painted liners are all unloading food: wheat, cheese and butter from Canada; mutton from New Zealand; canned eggs from China; pork from the Netherlands. Watch the newcomer as she is warped round a nasty cement corner of the entrance channel into the basin and then towards her berth. In a few minutes her hatches, like those of the other seven, are broached. The stevedores swarm into her holds and the donkey engines start whining and grumbling under the gravely moving derrick arms. Presently, what was an empty dock-section is heaped high with the cargo and a string of "goods vans" is toting it away. Follow it to a Government cold-storage place. Thence it emerges presently in wooden cases and is teamed to another dock, where sundry small steam trawlers lie waiting for errands to do. Their errand is now to take that beef, with probably a couple of military automobiles and a few thousand rounds of eighteen pounder shells, across the Channel to France. Watch the trawler as she quits her dock and gets out into the Thames, down past the old wooden wall of England, where she lies in the river, past the lightship at the Noro and the rows upon rows of nets and mines, and nets again, till she is in the open Channel. See what that is that circles her and her sister ships, protecting them against submarines. See them arrive at a French port that looks exactly like Quebec from the upriver side, and see the cargo land on French soil.

That load of bully beef is all but lost sight of in a great mound of stuff on the wharf. It lies there for many hours till finally a gang of workers clears it away and it resumes its journey by rail to a certain inland point. Here the long motor transports pick it up along with other goods, and it is distributed between several divisional depots. Its motor journey may last two days. When German Taubes appear overhead the convoy keep sunder the shade of the trees at the side of the road as much as possible. At night the long caravans lie hidden under avenues of trees if possible, and by day go on, closer and closer to the front. Occasionally, when an enemy airman has been able to spy the convoy and give the range, the convoy is shelled. It may lose some of its bully beef. There may be casualties, but the service has to be kept up across areas where the enemy has concentrated fire enough to daunt less courageous men. Yet in the midst of dangers the routine is still preserved. The officer in charge of the column collects written acknowledgements of the receipt of so much bully beef, so much pork, so much flour, and so on, from each depot. These in turn keep similar records.

In the stock of the commissariat there are not many dainties. Marmalade is about the best of them in ordinary times. But even that rule is abated as it gets toward Christmas. It is safe to say that there was probably more plum pudding in the British trenches in France this year than in all of Canada put together. And if in the list of extras which the military post brought the men there was nothing for certain men without friends of family back home, they would find themselves made partners in the things the more fortunate men received. For that is another point about the trenches; one man's wealth is for the moment every man's wealth. A ten-pound plum cake received by one man would probably yeild him just one fair-sized slice. The rest would be distributed in less than ten minutes.

It is June 1900, and the First Provisional Battalion is in Kroonstad, Orange Free State. It is composed of men who have been left behind because of illness or wounds. Eventually the battalion will catch up with the main body and the men will rejoin their regiments. No. 5 Company is composed of 17 members of

It is June 1900, and the First Provisional Battalion is in Kroonstad, Orange Free State. It is composed of men who have been left behind because of illness or wounds. Eventually the battalion will catch up with the main body and the men will rejoin their regiments. No. 5 Company is composed of 17 members of

The

The

One of our most agreeable duties [at the

One of our most agreeable duties [at the

The Canadians—many of them—salute only when necessary. They look upon this form of exercise as an inconvenience and unnecessary except when they meet their own officers. But, as in many other things, they are quickly learning to do the proper thing—to pay respect to the rank. British officers are sticklers for etiquette, consequently the British rankers are always very proper.

The Canadians—many of them—salute only when necessary. They look upon this form of exercise as an inconvenience and unnecessary except when they meet their own officers. But, as in many other things, they are quickly learning to do the proper thing—to pay respect to the rank. British officers are sticklers for etiquette, consequently the British rankers are always very proper.

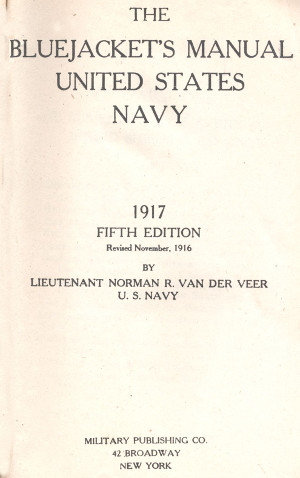

The Bluejacket's Manual, United States Navy, by Lieutenant Norman R. Van Der Veer, U.S. Navy, 1917

The Bluejacket's Manual, United States Navy, by Lieutenant Norman R. Van Der Veer, U.S. Navy, 1917

The Montpelier, Idaho, infantryman said later, "I felt something hit me on the arm. I thought it was the squad leader jabbing me.

The Montpelier, Idaho, infantryman said later, "I felt something hit me on the arm. I thought it was the squad leader jabbing me. The interdependence of men, especially in jungle warfare, has wrought what one officer called a revolutionary change in race relations in the military. Vietnam is the first war in which all U.S. units are thoroughly integrated.

The interdependence of men, especially in jungle warfare, has wrought what one officer called a revolutionary change in race relations in the military. Vietnam is the first war in which all U.S. units are thoroughly integrated. Earlier in the war, a U.S. 101st Airborne company was commanded by a Negro captain from Atlanta, Ga. The captain was articulate, well;-educated and very much the commander of his men.

Earlier in the war, a U.S. 101st Airborne company was commanded by a Negro captain from Atlanta, Ga. The captain was articulate, well;-educated and very much the commander of his men.

A day after he should have left Khe Sanh, the sergeant finally got his orders. His friends congratulated him. Home, today he was starting home.

A day after he should have left Khe Sanh, the sergeant finally got his orders. His friends congratulated him. Home, today he was starting home. A few hours later a Marine CH46 helicopter began spiraling down with a full load of replacements, men just starting their Vietnam tour.

A few hours later a Marine CH46 helicopter began spiraling down with a full load of replacements, men just starting their Vietnam tour.

London, November 4.—Canadian engineers have discovered at

London, November 4.—Canadian engineers have discovered at  The project began a year ago as a side-line to the

The project began a year ago as a side-line to the

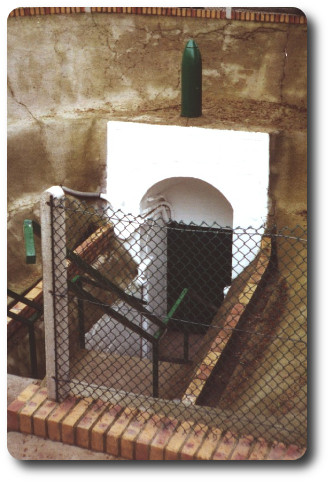

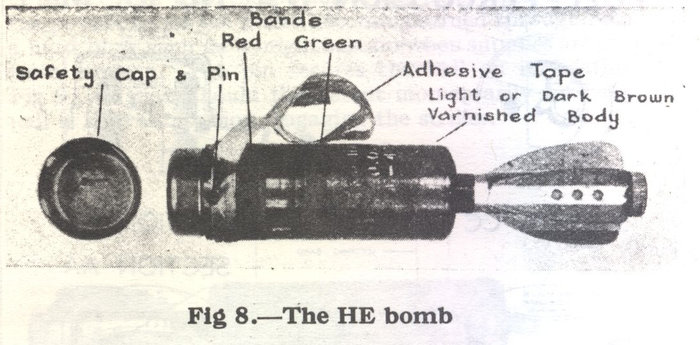

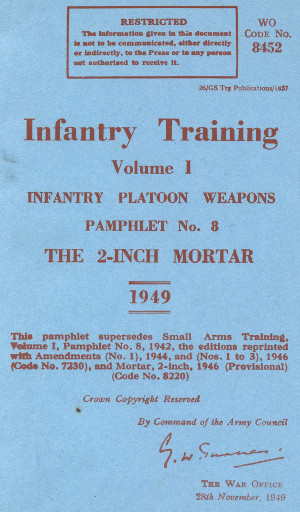

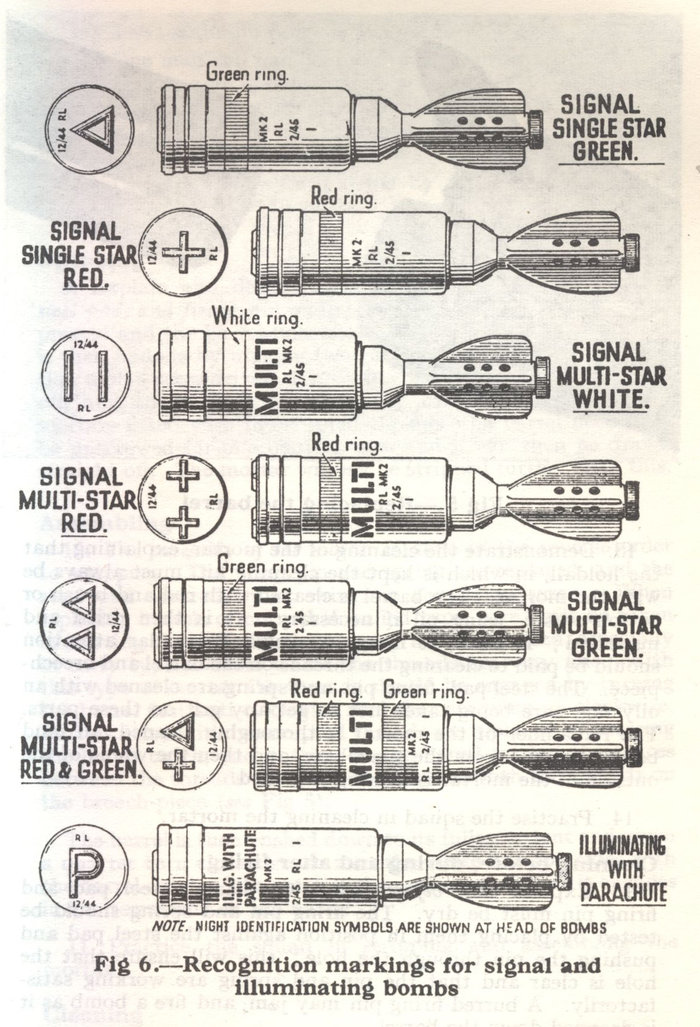

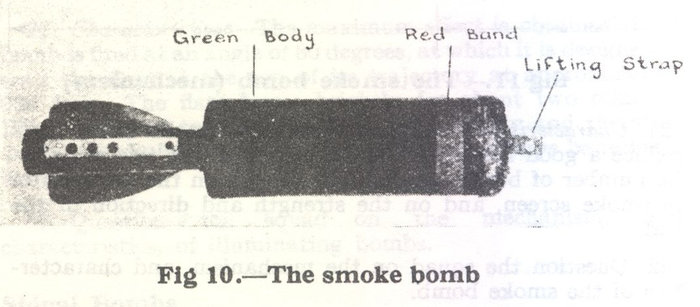

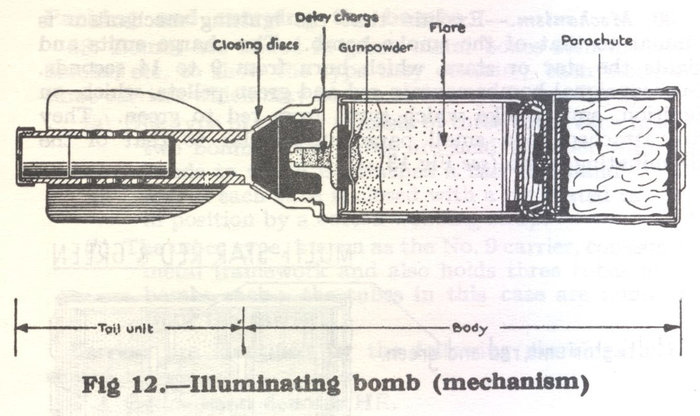

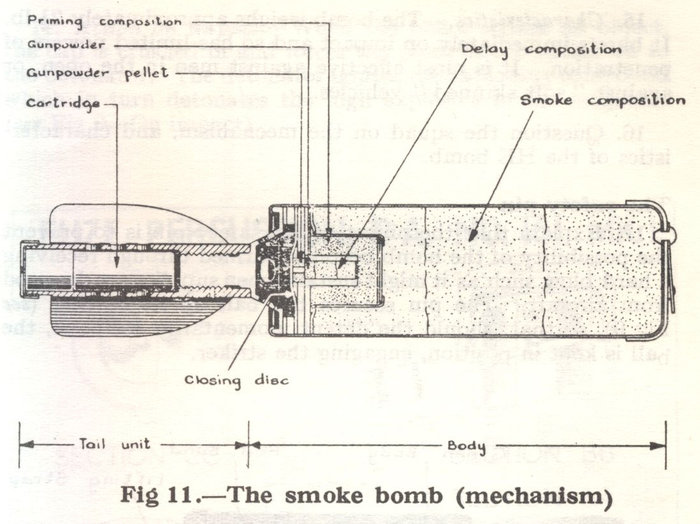

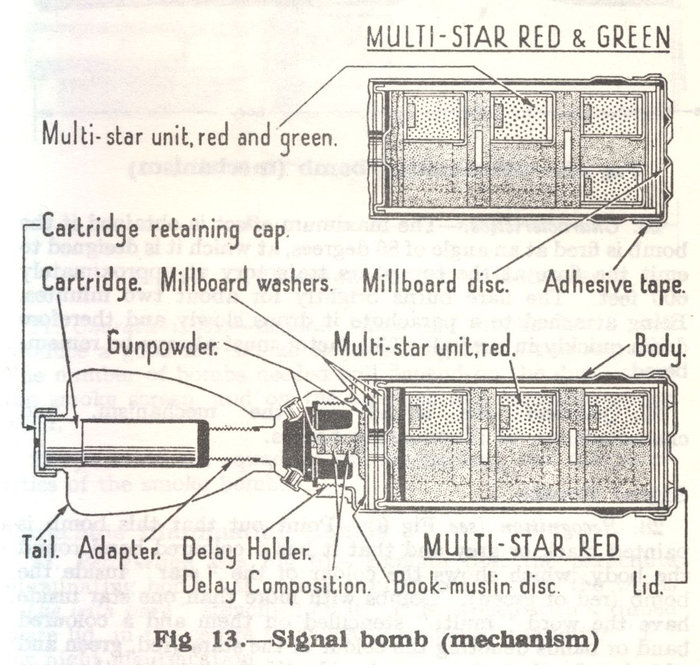

2-inch Mortar Ammunition (1949)

2-inch Mortar Ammunition (1949)

"Let me briefly tell you how the day is passed. Early in the morning, generally at half-past four, there is a scraping at the tent door, and a voice is heard, "Signoir alzate, vi prego, in cafe a pronto," to which a lisping voice responds, "What Thpero, it ith'nt five, thurely?'…'Si, signoir, vbicino a'le cinque,' cries the faithful old idiot (our best servants have been in lunatic asylums), and the British officer is soon up and doing, his coffee is drunk, biscuit and pork are consumed, a wallet is thrown across the shoulder, containing provender for the day, and a flask of rum; the sword is girt on, and away goes out companion to the trenches, there to remain until 6 p.m., leaving us to snooze away until the sun has afforded us a cheering supply of light and heat, when we rise from our bed of blankets, and, having drunk in pure air during the night, rush to breakfast with ravenous appetites.

"Let me briefly tell you how the day is passed. Early in the morning, generally at half-past four, there is a scraping at the tent door, and a voice is heard, "Signoir alzate, vi prego, in cafe a pronto," to which a lisping voice responds, "What Thpero, it ith'nt five, thurely?'…'Si, signoir, vbicino a'le cinque,' cries the faithful old idiot (our best servants have been in lunatic asylums), and the British officer is soon up and doing, his coffee is drunk, biscuit and pork are consumed, a wallet is thrown across the shoulder, containing provender for the day, and a flask of rum; the sword is girt on, and away goes out companion to the trenches, there to remain until 6 p.m., leaving us to snooze away until the sun has afforded us a cheering supply of light and heat, when we rise from our bed of blankets, and, having drunk in pure air during the night, rush to breakfast with ravenous appetites.

We had two tanks with us (this was three days later) the most of the way, and for artillery fire—well, hell was let loose. It was terrible.

We had two tanks with us (this was three days later) the most of the way, and for artillery fire—well, hell was let loose. It was terrible.

If

If

London, May 12.—A court-martial is in progress at Dublin against certain officers of the

London, May 12.—A court-martial is in progress at Dublin against certain officers of the  London, 13th February.—The whole absurd story of how the fashionable young bloods of the

London, 13th February.—The whole absurd story of how the fashionable young bloods of the  London, 22nd April.— In conformity with the instructions given by

London, 22nd April.— In conformity with the instructions given by