Vietnam Sketchbook (Part 1)

Topic: The Field of Battle

Vietnam Sketchbook (Part 1)

War's Something More than Charts, Headlines

Eugene Register-Guard, 18 August 1968

By John T. Wheeler, of Associated Press

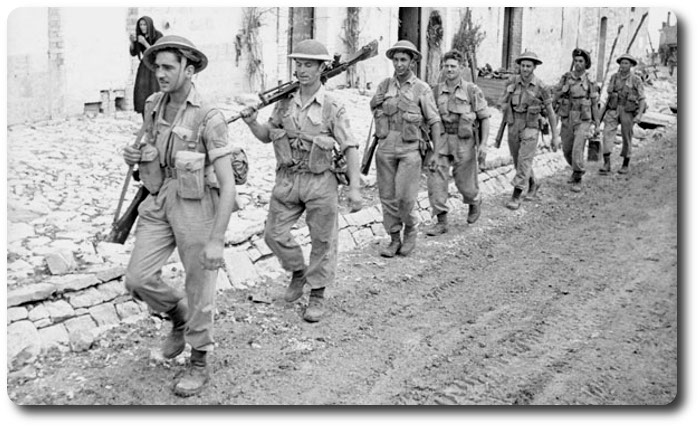

There's more. Much more, to the war in Vietnam than battle reports and casualty figures, statistics and strategy. Above all, there are the soldiers, the "GI Joes," each fighting for his life in a very personal way, in his own personal war. John Wheeler, who has been covering Vietnam for The Associated Press for years, recounts some of those personal experiences, funny and bitter, tragic and ironic, that make up the war in Vietnam.

SAIGON—In the battlefield, where the killing is done, the chaos of war makes a mockery of the neat, mimeographed battle plans and colored symbols arranged on wall maps back at headquarters.

For in the field, an incautious step, a minute flaw in a howitzer's sights, a commander's mistake, fortune's whimsy—almost anything—can kill a man or cripple his body.

Most GIs learn to conquer or control their fear of the predictable dangers of combat. But many find dealing with chaos and the bitter ironies it spawns a much tougher proposition.

They find that life—and death in the rice paddies, swamps, jungle and mountains often is the direct opposite of their backgrounds in a well-ordered civilization where the question "Why?" usually has an answer.

For the combat infantryman here, the question often is not only unanswerable but unasked.

For one Marine sergeant, the ironies piled up one atop the other at the very end of his 13-month tour in Vietnam.

During the hectic days of the siege at a Khe Sanh, routine paperwork often was delayed. One piece of late paperwork contained the order for the leatherneck to go home.

A day after he should have left Khe Sanh, the sergeant finally got his orders. His friends congratulated him. Home, today he was starting home.

A day after he should have left Khe Sanh, the sergeant finally got his orders. His friends congratulated him. Home, today he was starting home.

The sergeant joked with his comrades in the trenches until the morning fog lifted and it was time to go to the airstrip for the last ride out.

Looking toward a hill infested with hidden North Vietnamese troops, the Marine emptied his pistol in their general direction. "Well, those are the last shots I'll fire in Nam," he said and climbed out of the trench.

Moments later, one of the 800 shells that hit Khe Sanh that day exploded near the sergent, sending steel splinters into his body.

Later when he was being evacuated by helicopter, he could muse not only on the red tape, but that he had won a much undesired third Purple Heart.

Under Marine regulations the third Purple Heart automatically means a man is sent out of the war zone no matter how long or short a time he had spent in Vietnam.

GIs are deeply superstitious about being "short-timers," men who are near the end of their combat tours. There have been many cases where battlefield savvy, extreme care and an unbroken chain of luck have failed a man at the last moment.

The sergeant major of one Marine battalion in the demilitarized zone area was within 14 days of returning to the States after fighting in his third war. In two months he would leave the military for good and retire.

One of his men called the grizzled veteran "the mole" because of the way he stayed near his sandbagged bunker.

One day during a prolonged lull in the routine enemy shelling, the sergeant major crawled out of his bunker and headed rapidly for the foxhole of another oldtimer who had hot coffee.

The lull ended midway between the bunkers and the sergeant major was killed instantly.

A few hours later a Marine CH46 helicopter began spiraling down with a full load of replacements, men just starting their Vietnam tour.

A few hours later a Marine CH46 helicopter began spiraling down with a full load of replacements, men just starting their Vietnam tour.

As usual, Communist mortar and artillery shells began dropping around the off-loading area as soon as the chopper landed. An 18-year-old Marine who had been in Vietnam only two days sprinted out the back door of the chopper and raced toward the safety of a trench line 100 yards away.

An older man, cursing his age and slowness was clear of the blast from the shell that exploded virtually at the private's feet 40 yards ahead. The youngster had led the field, but lost the race. He was the only one of 25 men to be hit.

Although the war unquestionably brutalizes most men who fight it, GIs sometimes voice another side they see to the coin.

A young, sandy-haired corporal from St. Louis stared into his half-emptied can of cold C rations and said:

"Somehow we're both better and worse than we were before we were pushed into this war up to our necks.

"Half the things I've seen and done here I hope I never have to think about again. And I sure wouldn't want my wife or family to know some of the things I've had to do.

"But at the same time there are times when we are all better than we were. I've never known friendship like I've found here. There isn't anything I wouldn't do for the guys in my fire team. And I sleep better knowing most of them feel the same way. Yeah, that's it. Sometimes we are better."

The better side, as the corporal called it, is the wellspring for much of the positive side of the war—heroism, endurance, determination and sacrifice—sometimes the ultimate sacrifice of giving your life for your comrades.

Many in Vietnam have heard the thump of an anemy grenade landing near them and in the midst of their comrades. Sometimes the grenade is on a trail, sometimes in a shell hole, sometimes among men huddled behind trees or termite mounds firing at an enemy only yards away.

More than a score of men have reacted instinctively—there is no time to pause and consider—by throwing themselves on the grenade to save their friends. The results normally are fatal to the man who cared enough.

Some men welcome war as a personal proving ground. Because they are in some way unsure of themselves, they press harder than most, taking reckless chances that will put some nagging fear or uncertainty to rest. Often these men return to the United States with several rows of ribbons on their chest. Often they go home in caskets, the questions and proof no longer relevant.

"You know, I'm going to sign over for another tour when my 12 months is up," a beardless 24-year-old lieutenant nicknamed Buddy said one night in the central highlands.

"This is the life for me, I'm going to try to stay in Vietnam for as long as the Army'll let me."

The next day Buddy's company was caught in an ambush which killed or wounded half the unit. Buddy was killed early in the action, leading a counterattack at the head of his men.

Only later did a correspondent who was with the unit learn from a family friend that Buddy was the son of a much-decorated World War II Army officer who was killed in action.

"All through childhood Buddy tried to live up to the standards of a father he had never known," the friend said.

No one questions the courage of the American fighting man and not a few tributes have come from the enemy which sets some pretty high standards for its own men. But the idea that Americans always charge into the guns or are spoiling for a fight isn't true.

In one instance an American unit under heavy fire lay behind what cover it could find. They had been ordered to assault up the hill. The sergeant called out the order, "When I count three, everyone move out." the order was passed down the line without elaboration. Minutes later the sergeant called out loudly, "One. Two. Three. Go." Everyone, including the sergeant, began running toward the rear—away from the hill.

"Nobody is going to be interested in that hill in a couple of days," the sergeant explained later. "We would have taken two or three men killed for each one we got. Those are very bad odds."

Posted by regimentalrogue

at 12:01 AM EDT

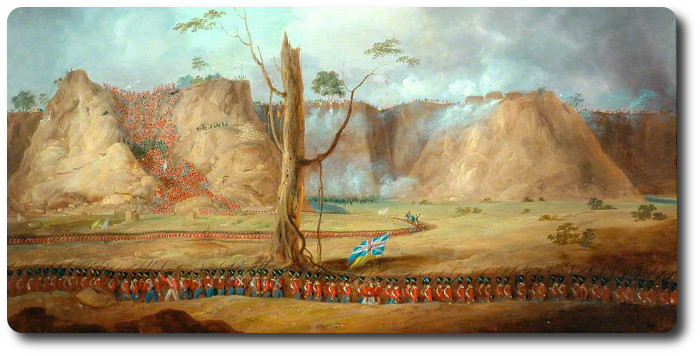

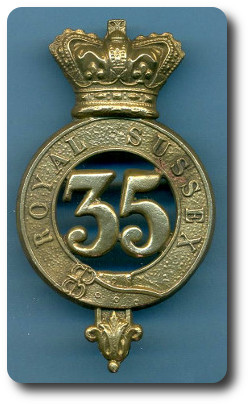

It is June 1900, and the First Provisional Battalion is in Kroonstad, Orange Free State. It is composed of men who have been left behind because of illness or wounds. Eventually the battalion will catch up with the main body and the men will rejoin their regiments. No. 5 Company is composed of 17 members of

It is June 1900, and the First Provisional Battalion is in Kroonstad, Orange Free State. It is composed of men who have been left behind because of illness or wounds. Eventually the battalion will catch up with the main body and the men will rejoin their regiments. No. 5 Company is composed of 17 members of

The

The

One of our most agreeable duties [at the

One of our most agreeable duties [at the

The Canadians—many of them—salute only when necessary. They look upon this form of exercise as an inconvenience and unnecessary except when they meet their own officers. But, as in many other things, they are quickly learning to do the proper thing—to pay respect to the rank. British officers are sticklers for etiquette, consequently the British rankers are always very proper.

The Canadians—many of them—salute only when necessary. They look upon this form of exercise as an inconvenience and unnecessary except when they meet their own officers. But, as in many other things, they are quickly learning to do the proper thing—to pay respect to the rank. British officers are sticklers for etiquette, consequently the British rankers are always very proper.

The Bluejacket's Manual, United States Navy, by Lieutenant Norman R. Van Der Veer, U.S. Navy, 1917

The Bluejacket's Manual, United States Navy, by Lieutenant Norman R. Van Der Veer, U.S. Navy, 1917

The Montpelier, Idaho, infantryman said later, "I felt something hit me on the arm. I thought it was the squad leader jabbing me.

The Montpelier, Idaho, infantryman said later, "I felt something hit me on the arm. I thought it was the squad leader jabbing me. The interdependence of men, especially in jungle warfare, has wrought what one officer called a revolutionary change in race relations in the military. Vietnam is the first war in which all U.S. units are thoroughly integrated.

The interdependence of men, especially in jungle warfare, has wrought what one officer called a revolutionary change in race relations in the military. Vietnam is the first war in which all U.S. units are thoroughly integrated. Earlier in the war, a U.S. 101st Airborne company was commanded by a Negro captain from Atlanta, Ga. The captain was articulate, well;-educated and very much the commander of his men.

Earlier in the war, a U.S. 101st Airborne company was commanded by a Negro captain from Atlanta, Ga. The captain was articulate, well;-educated and very much the commander of his men.

A day after he should have left Khe Sanh, the sergeant finally got his orders. His friends congratulated him. Home, today he was starting home.

A day after he should have left Khe Sanh, the sergeant finally got his orders. His friends congratulated him. Home, today he was starting home. A few hours later a Marine CH46 helicopter began spiraling down with a full load of replacements, men just starting their Vietnam tour.

A few hours later a Marine CH46 helicopter began spiraling down with a full load of replacements, men just starting their Vietnam tour.

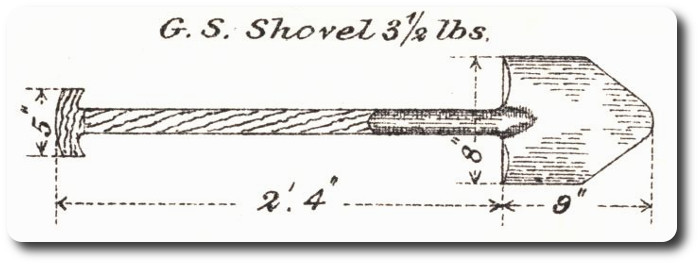

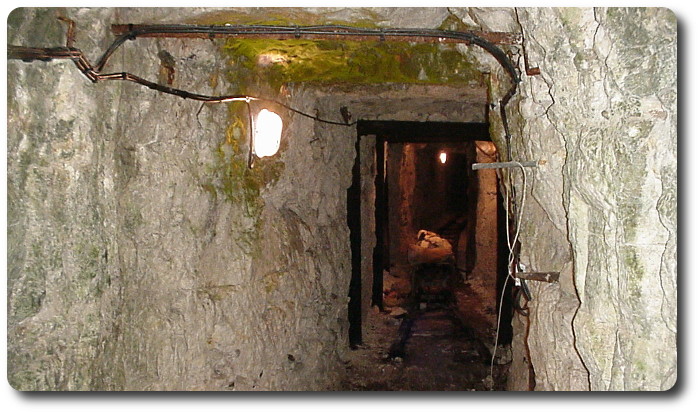

London, November 4.—Canadian engineers have discovered at

London, November 4.—Canadian engineers have discovered at  The project began a year ago as a side-line to the

The project began a year ago as a side-line to the

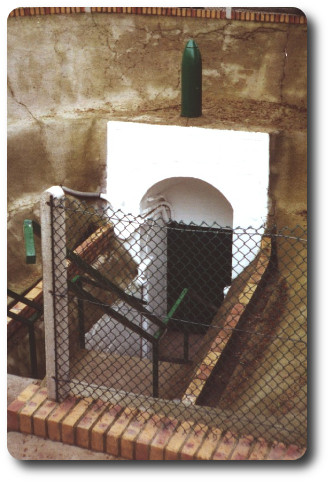

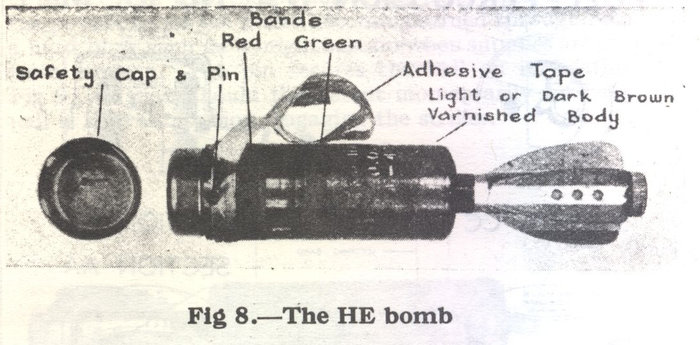

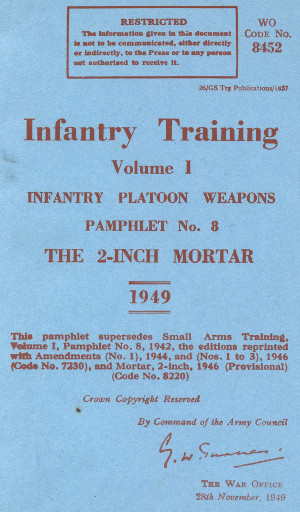

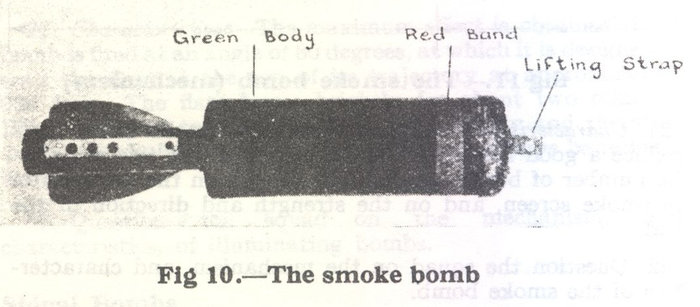

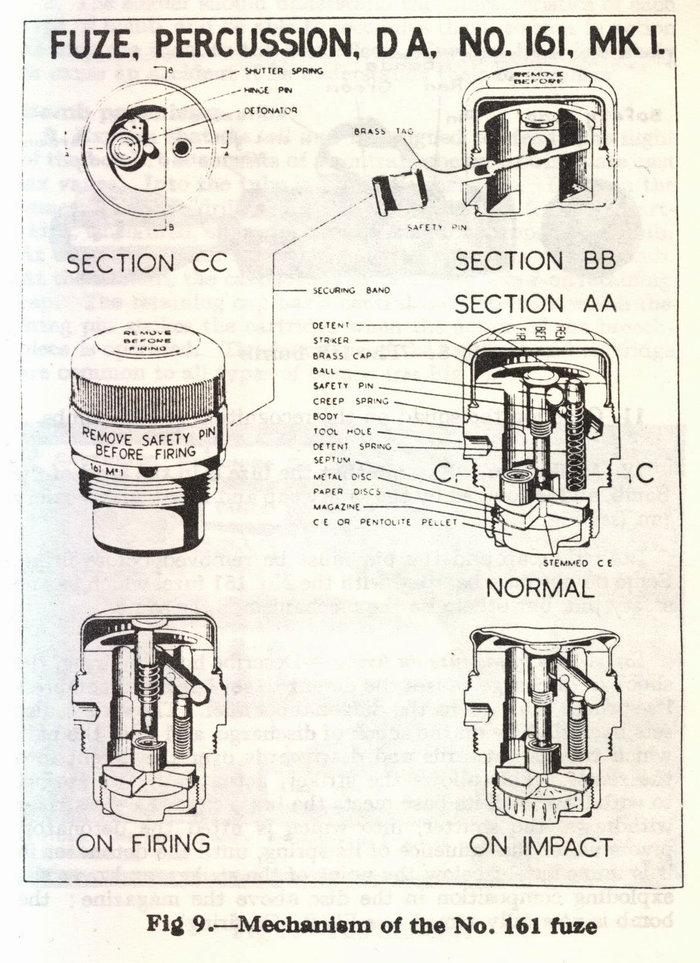

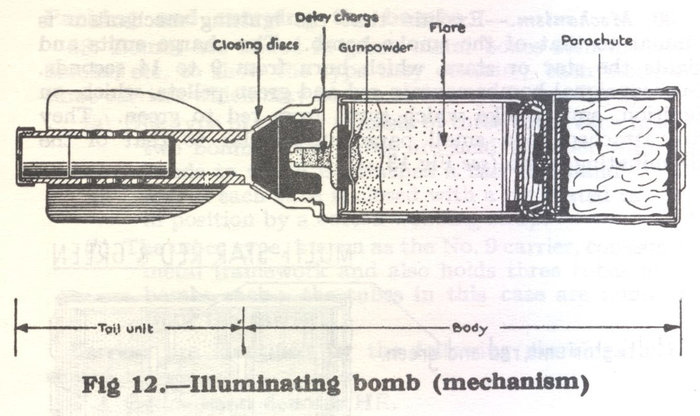

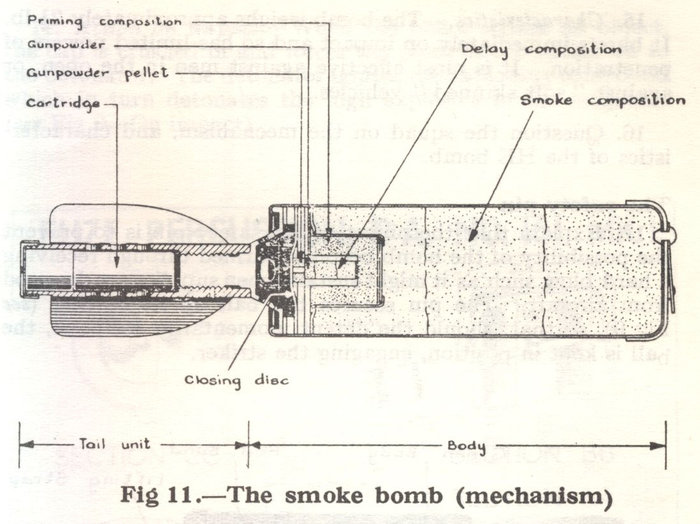

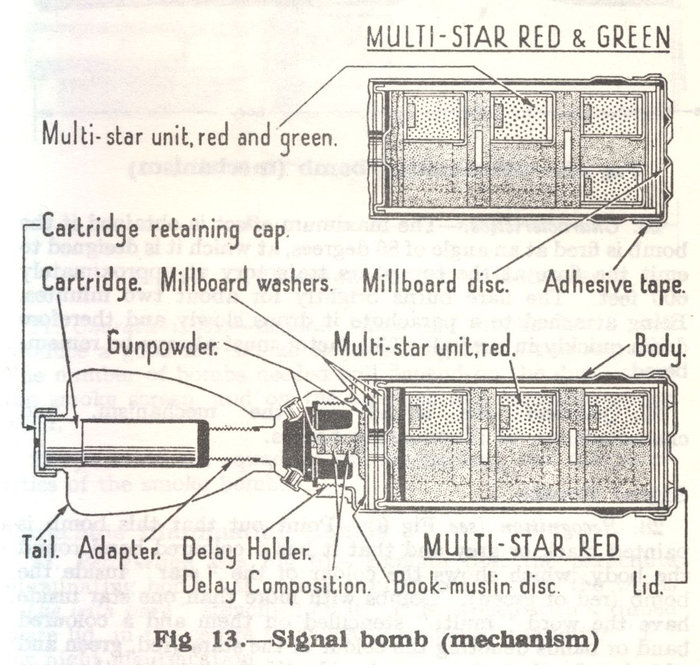

2-inch Mortar Ammunition (1949)

2-inch Mortar Ammunition (1949)

"Let me briefly tell you how the day is passed. Early in the morning, generally at half-past four, there is a scraping at the tent door, and a voice is heard, "Signoir alzate, vi prego, in cafe a pronto," to which a lisping voice responds, "What Thpero, it ith'nt five, thurely?'…'Si, signoir, vbicino a'le cinque,' cries the faithful old idiot (our best servants have been in lunatic asylums), and the British officer is soon up and doing, his coffee is drunk, biscuit and pork are consumed, a wallet is thrown across the shoulder, containing provender for the day, and a flask of rum; the sword is girt on, and away goes out companion to the trenches, there to remain until 6 p.m., leaving us to snooze away until the sun has afforded us a cheering supply of light and heat, when we rise from our bed of blankets, and, having drunk in pure air during the night, rush to breakfast with ravenous appetites.

"Let me briefly tell you how the day is passed. Early in the morning, generally at half-past four, there is a scraping at the tent door, and a voice is heard, "Signoir alzate, vi prego, in cafe a pronto," to which a lisping voice responds, "What Thpero, it ith'nt five, thurely?'…'Si, signoir, vbicino a'le cinque,' cries the faithful old idiot (our best servants have been in lunatic asylums), and the British officer is soon up and doing, his coffee is drunk, biscuit and pork are consumed, a wallet is thrown across the shoulder, containing provender for the day, and a flask of rum; the sword is girt on, and away goes out companion to the trenches, there to remain until 6 p.m., leaving us to snooze away until the sun has afforded us a cheering supply of light and heat, when we rise from our bed of blankets, and, having drunk in pure air during the night, rush to breakfast with ravenous appetites.

We had two tanks with us (this was three days later) the most of the way, and for artillery fire—well, hell was let loose. It was terrible.

We had two tanks with us (this was three days later) the most of the way, and for artillery fire—well, hell was let loose. It was terrible.

If

If