Topic: British Army

England's Indian Army of 238,000 Is Available for Service in Europe

Forces Include the Ghurkas, Who Fight Like Wildcats, and the Gigantic Sikhs and Pathans—Several Crack Regiments of British Are Also There

Meriden Morning Record, Meriden, Connecticut, 31 August 1914

(New York Herald.)

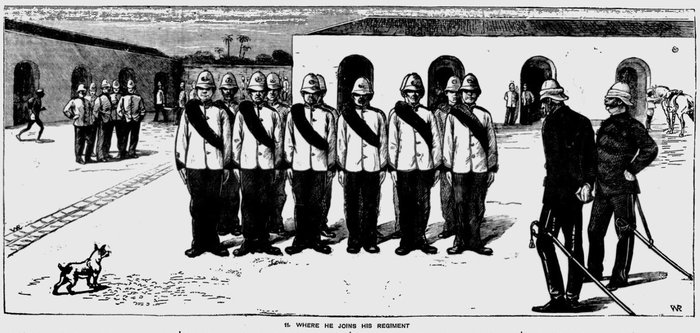

England if necessary can pour into France from India 238,000 trained men, of which 75,000 are British troops, including some of the crack regiments of the royal army, and the 163,000 remaining are the fighting native troops of the Indian army, fit comrades on the firing line of France's Turcos and Spahis.

According to official figures the Indian army's strength in round numbers, is as follows: Infantry, 122,000; cavalry, 25,000; artillery, 10,000; engineers, etc., 6,000; total 163,000. Of this number 3,000 are English officers and non-commissioned officers; the rest are natives.

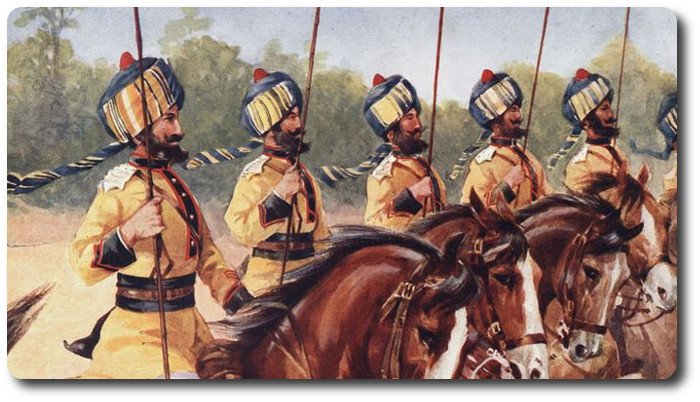

Thirty-nine regiments of cavalry, fifteen of them Lancers regiments, besides the bodyguard troops of the governor general and of the governors, and several independent troops, make up the mounted arm.

The main strength of the Indian army is in its infantry. Brahmans, Rajputs, Jats, Sikhs, Punjabis, Dogras, Mahrattas and Ghurkhas, of all castes and of several religions—Mohammedan, Hindoo, Buddhists—are all warriors who will lay down their lives in eagerness for the British Raj, and the dark skinned regiments of the Indian army form a fighting force hard to stop.

Ghurkas Natural Fighters

Among the most interesting as well as the most formidable fighting outfits in the Indian army are the Ghurkas. There are ten regiments of Ghurka rifles. These little fighters, who come from the region of Nepal, and who trace their descent from the Rajputs, would rather fight than eat. In appearance the Ghurkas are deceiving. They are short, stocky little men, of somewhat the appearance of the Japanese, although a little heavier. And they wear perpetual grins on their faces. The grin does not come off when they go into a fight.

The Ghurkas were conquered by the British in 1814 after years of fighting, and have become loyal subjects of England. When the Ghurka regiments were first made part of the Indian army they did not seem to take well to organized methods of warfare. It was not until the army authorities allowed them to make their national weapon, the kukri, part of their equipment that they regained their fame as fighters. The instructors could never make them use the bayonet. The kukri is a long, heavy curved knife.

Fight With Long Knives

In close quarters the Ghurka throws away his rifle and takes to the kukri, which he uses with telling effect. When charged by cavalry the Ghurkas stand up and fire at the horsemen until they are within sabering distance, when the natives fall. As the charging horsemen pass over them the little warriors are up and hamstringing the horses or clinging to the saddles and stabbing the riders.

This method of fighting is not unlike that of the Turcos of the French army, who also "play ‘possum" when charged by a heavier enemy, only to rise and take the attackers from the rear as soon as they have passed over them. Neither Ghurkas nor Turcos, however, do much defensive fighting except against cavalry, for they are usually leading any charge that may be taking place in their vicinity.

There seems to be a natural affinity between the Ghurka and the Scotch Highlander regiments. Like the Scotchmen, the Ghurkas use bagpipes, and their pipes accompany them on the firing line. Time and time again in Great Britain's campaigns overseas have the big Highlanders and little brown skinned Ghurkas charged side by side. The Ghurkas look down upon other colonial troops, but fraternize with white soldiers.

Would Surprise Germans

If the German infantrymen come face to face with a wave of charging Gurkas gone "musth" with the lust of battle and using their knives the Kaiser's troops will receive the surprise of their lives. The Ghurkas will not stop when once launched in a charge until, like the wildcats that they are, they come to grips with their opponents.

In direct contrast to the Ghurkas are the big Sikhs. Six footers all, slow, methodical, steady under fire, the Sikhs when once on the firing line will rather die in their tracks than retreat. The Sikhs have been loyal soldiers ever since the British took India. During the Indian mutiny the Sikhs fought and died beside their white officers, always faithful to their trust.

The Pathans are also big men. They are on the same order as the Sikhs, only quick thinkers and livelier on their feet. Sikh and Pathan both are fond of cold steel and always give good account of themselves in bayonet charges.

The artillery of the Indian army proper consists of eleven mountain batteries and one horse battery, beside garrison artillery.

There are three regiments of sappers and miners, and seven signal companies in the engineers corps.

Crack Regiments There

The British troops in India consist of 54,000 infantry, 5,000 cavalry and 16,000 artillery. The famous cavalry regiments of England at present serving in India are the First and Seventh Dragoon Guards, the Inniskilling Dragoons, the Queen's Own, Royal Irish, Thirteenth and Fourteenth Hussars and the Seventeenth and Twenty-first Lancers. The last named regiment, sometimes known as the Bengal Lancers, is now called the Empress of India's.

Eleven batteries of the Royal Horse artillery and forty-five batteries of the Royal Field Artillery are in India, besides twenty-six batteries of garrison artillery. It is improbable that these last would be moved unless to reinforce Great Britain's own coast defences.

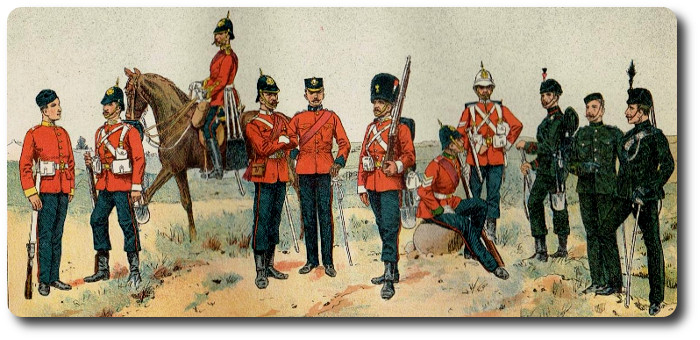

Many of England's crack infantry regiments have battalions in India. Among them are the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, Berkshire, Border, Cameron Highlanders, Cheshire, Connaught Rangers, Dorsetshire, Dublin Fusiliers, Durham Light Infantry, Hampshire, Highland Light Infantry, Inniskilling Fusiliers, Irish Fusiliers, Royal Irish, Irish Rifles, Kent East (The Buffs), Kent West (Queen's Own), King's, King's own Scottish Borderers, King's Royal Rifles, Lancashire Fusiliers, Loyal North, Prince of Wales Volunteers, Leistershire, Leinster, Middlesex, Munster Fusiliers, Norfolk, Northumberland, Rifle Brigade, Royal Fusiliers, Royal Scots, Black Watch, Seaforth Highlanders, Somerset Light Infantry, Staffordshire, Surrey, Sussex, Welsh, West Riding, York and Lancaster, and Yorkshire Light Infantry regiments.

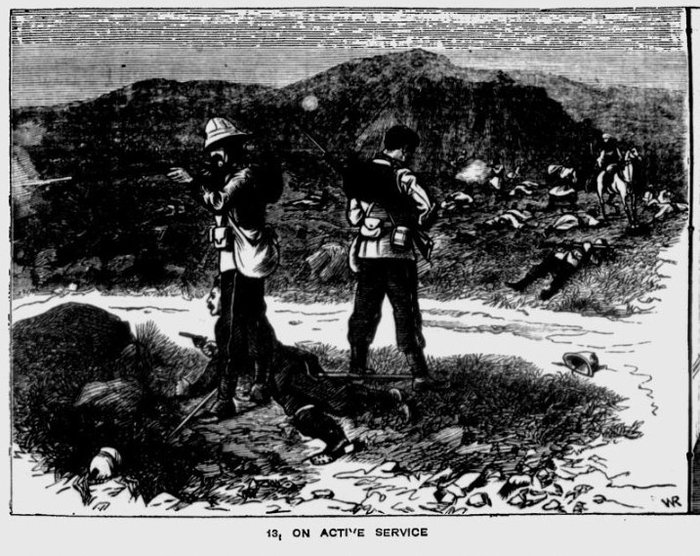

Well, I've got back to camp again. We have had a rough twenty-four hours of it; it rained nearly the whole time. The enemy kept pitching shell into us nearly all night, and it took us all our time to dodge their Whistling Dicks (huge shell), as our men have named them. We were standing nearly up to our knees in mud and water, like a lot of drowned rats, nearly all night; the cold, bleak wind cutting through our thin clothing (that now is getting very thin and full of holes, and nothing to mend it with). This is ten times worse than all the fighting.

Well, I've got back to camp again. We have had a rough twenty-four hours of it; it rained nearly the whole time. The enemy kept pitching shell into us nearly all night, and it took us all our time to dodge their Whistling Dicks (huge shell), as our men have named them. We were standing nearly up to our knees in mud and water, like a lot of drowned rats, nearly all night; the cold, bleak wind cutting through our thin clothing (that now is getting very thin and full of holes, and nothing to mend it with). This is ten times worse than all the fighting.