The Why of the Trenches

Topic: CEF

The Why of the Trenches

Practical Points from a Practical Soldier on the Use of Front Line Positions, with Some Suggestions to the Men Who Are New at the War Game on the Routine and Life at the Extreme Front

The Milwaukee Sentinel, 29 September, 1917

By Captain David Fallon, M.C. (Late of the British and Australian Forces)

Although this article isn't specifically about the CEF, it has been tagged as such to keep it with other First World War material.

To those who have never interested themselves in military matters the trench fighting on the western front in Europe seems to be very new tactics, but to the student of military history it is more than two thousand years old. Never before, however, has it been so perfectly organized.

The first time in history field fortifications and obstacles in the field were used to keep back the attacking forces they were constructed in China. They were built by the then emporer of China to keep away marauding Tartarsand wild men of Northern Asia. The remains of this fortification system we know as the Great Wall of China, about 1,500 miles long, 300 feet high, and 50 feet in width.

Before the Romans attacked any position they would dig themselves in and build fortifications to hide their forces from their opponents. The American civil war developed much trench fighting, and a good example of this kind of warfare was seen in the Russo-Turkish War of 1878. At the battle of Plevne the Turks, under Osman Pacha, were seriously outnumbered in men and munitions. Osman Pacha, remembering an old axiom which says, "When a force is outnumbered in men and munitions they must build fortifications to be able to hold their own territory, for a trained man strongly intrenched is equal to forty of the opposing forces," told his army to "dig in." This maxim has proved still good, for at the battle of the Marne and the Aisne the British and french troops dug themselves in so quickly that the Prussians thought that they had literally disappeared.

One of the great defensive incidents of the war occurred in Belgium when General Leman, commanding the Leige defences, with only thirty hours' start made such fortifications that he was able for ten days to withstand the constant onslaught of five of the best trained and equipped corps of German forces.

Although the intensive kind of fighting now in progress abroad is new to America, yet you possess, as I have learned, "the art of adaptation which seems to grow with you" and comes natural to many. You will, therefore, have no difficulty in adapting yourselves to the present kind of fighting, which you soon will be called upon to wage.

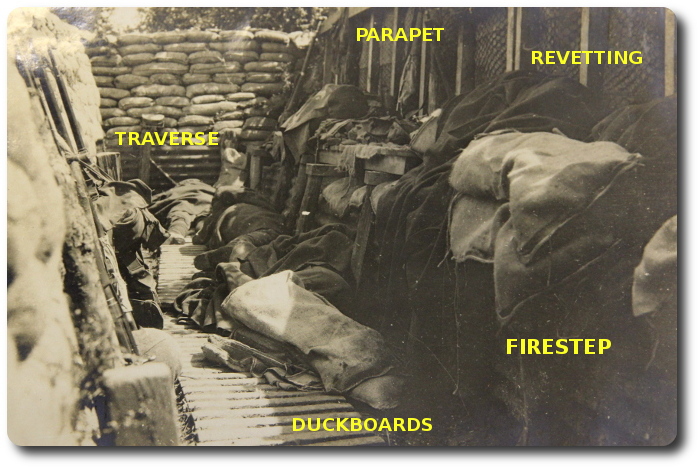

Trenches are systems of openings in the ground and fortified in such a way as to permit a soldier to reist an attacking force. The purpose of trenches is to protect men in them from fire and thus enable them to fight against more than their number of the enemy. There are three kinds of trenches, each for an entirely different purpose:—

- First—Front line fire trenches, in which men fight.

- Second—Sheltered trenches, in which the supports and reserves rest, protected from fire and also from the weather.

- Third—Communicating trenches, which act as safe paths from the sheltered trenches to the fire trenches.

If you would become acquainted with trench life in winter dig a hole in the ground six feet deep and two feet wide, fill it three-fourths full with water and stand in it. Carry sixty pounds on your back and eight pounds on your head and get some one to throw water continuously over you. Your supply of food must first of all be dropped into the hole; then get the assistance fo two of your friends and tell them to keep up a continuous bombardment with bombs, which can be improvised by filling a jam tin with needles, old nails, and amonal—or any such explosive will do—then set the fuse, which should be lighted and thrown on the ground surrounding your position.

In summer dig the same hole at an abattoir an "carry on" as in winter.

This ought to give even the unimaginative some conception of trench life.

Trenches serve the same purpose as armor used to against men without armor. In making armor, its shape, and thickness depended upon the sort of blows it would have to withstand, whether from swords or arrows. In the making of trenches in the same way the sorts of fire which they will have to guard against are the thing that decides what their shape will be. The sorts of fire which the Allies are subjected to are, first, rifles and machine guns, in which are used the same bullets, and therefore can be regarded as the same weapon; second, artillery fire.

In order to make trenches suitable for protecting men from these two kinds of weapons we must consider what the effects of their fire is in each case. Rifle bullets in this war are always fired at trenches from very short range, normally fifty to three hundred yards. The skim over the ground in a flat, level course and may be regarded at this short range as travelling in as direct a line as the rays of a searchlight. Therefore, as long as a man has any kind of bullet proof cover which hides him from the front he is safe.

A man during his first appearance in the trenches will be eager to look over the top of the parapet and see what all it means. Periscopes are provided for this purpose to obviate any chance of the man being hit. One day one of my men, after doing duty in the trenches for ten days without a wash or shave, looked into the periscope through the wrong mirror, and instead of seeing what was going on in No Man's Land he saw his own reflection in the mirror, but, not having seen his own reflection for some time, he dropped the periscope, rushed for his rifle and remarked, "There's a damned ugly Boche looking into my periscope.

Every night the front part of the trench should be inspected for breaches, which may be caused by regular sniping from the from the front. This is a regular practice of snipers, and many a man has paid with his life for this neglect. One day I took over some trenches, and the officer explained that they had lost one officer and six men before they tumbled to the game.

Artillery shells fired from a distance of, say, two miles are fired upward in the air in order to carry such a distance, much as a baseball player throws the ball if he wishes it to reach a long distance. As a result of this, artillery shells as the approach a trench are falling as well as moving forward. They slant then somewhat like the rays of the sun. If the sun is high in the sky a man to get shelter behind a wall from its heat must crouch down and sit very close to it. To give protection from a shell the trench must be deep and have a steep side, under which a man can crouch. A shell may fall into a trench although it safely passes over the head of the man in it. It will then burst and probably will kill or wound the men in that length of trench. The war has produced many incidents where men have picked up a shell and have thrown it over the parapet, thus saving the lives of their comrades. It is necessary to prevent shells from falling into the mouth of the trench. To do this a trench must be short and narrow, so as to make the mouth of it as small as possible. A rule which you must remember is this:—

"The shorter and narrower a trench is the safer it is."

Again, "The lower a man can crouch in a trench the safer he will be from pieces of a shell which bursts close to the trench.' This brings another rule which must be remembered:—

"The deeper the trench the safer it is."

The continuous bombardment of these trenches levels them to the ground and keeps the men perpetually busy rebuilding them. Even when one is dog tired there must be no slackness or indifference in the reconstruction, otherwise men will pay the penalty for their lethargy. It is obvious that a trench not easily visible is less likely to be shelled than one which is conspicuous. From this can be formulated:—

"The better hidden a trench the safer it is."

Artists, painters, and decorators are used to make screens with which to hide the artillery. If this were not done no battery could escape the eagle eye of the aviator. Dummy trenches are often made to amuse the boys in the trenches. A man is sent along with plenty of black powder, and during one of the bombardments he is told to light the powder. The thick black smoke which ensues catches the Boche's eye and he thinks that is where the guns are, so they train all the guns on the dummy trenches, much to the amusement of the boys.

In taking over a line of trenches the men are formed up and receive their food, water and ammunition. The are led by guides and are marched through the communicating trenches in single file to the front line trenches, some going to the support and others to the reserve lines. Units should not move along the trenches more than sixty strong, and men should not be too close together, for any shell that might drop into the communicator would kill or wound more than is absolutely necessary. This gives us another rule:—

"Don't crowd the communicator [trench]."

Officers, non-commissioned officers and men, on handing over their particular posts, should explain to the incomers the extent of the trench, who are on the flanks, dumps, continuity, bombs, ammunition, &c.

The usual routine in the trenches provides for the inspection of rifles twice daily—morning and evening, and every precaution must be taken to keep all other equipment in good order. The chief problem to be faced in the ordinary routine of trench work is to insure the maximum amount of work daily toward the subjection and annoyance of the enemy and the improvement of the trenches consistent with the necessity for every man to get the proper amount of rest and sleep. This can be done only by a good system. A definite programme and time tables of work must be arranged and adhered to as far as possible. A simple system by which a unit in the trenches obtains the material required for the construction and repair of the trenches has been worked out.

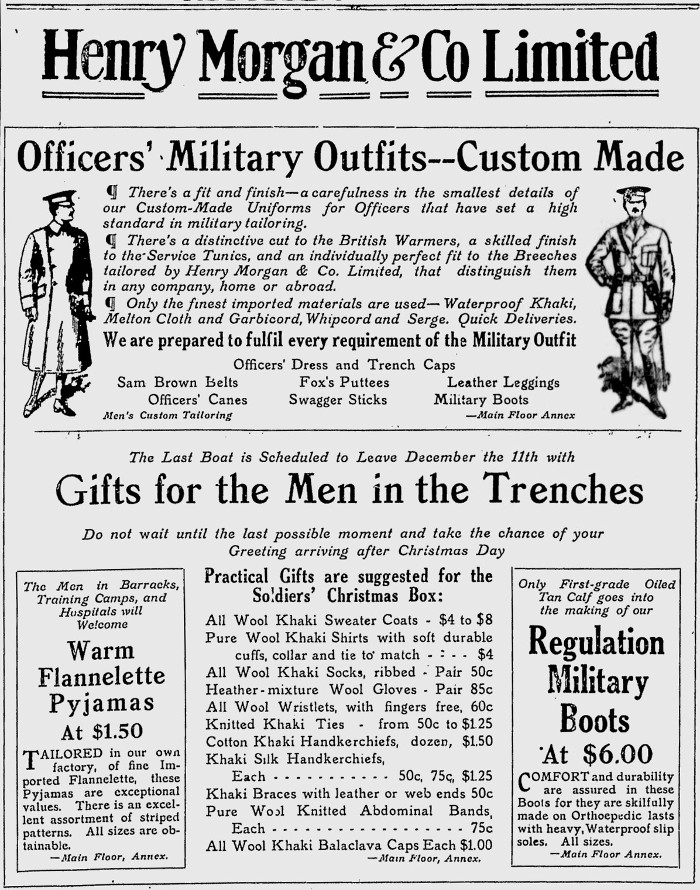

In every regiment a "regimental workshop" is usually formed, the necessary personnel (from twelve to twenty men) being found in the battalions who are carpenters and artificers by trade. This establishment is as near to the trench line as possible consistent with the men being able to work in reasonable safety. Its functions are to make up the material obtained from the engineers into shapes and sizes suitable for carrying up to the trenches and to construct any simple device required for use in the trenches, such as barbed wire, knife rests, box loop holes, rifle rests, floor gratings, grenade boxes and sign boards for communicating trenches with which to guide one where to go.

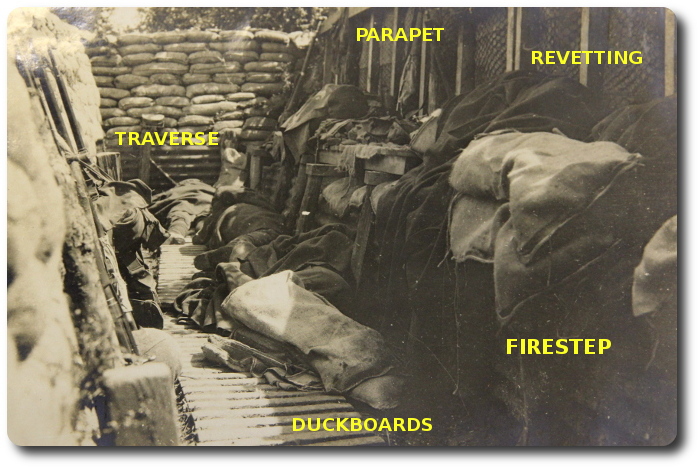

The importance of working on a definite system and with a definite programme has already been emphasized. The essential requirements for a front line trench are:—

(a) The parapet must be bullet proof.

(b) Every man must be able to fire OVER the parapet with proper effect (that is, so that he can hit the bottom of his own wire).

(c) Traverses must be adequate.

(d) A parados must be provided to give protection against the back blast of high explosives.

(e) The trace of the trench should be irregular to provide flanking fire and if the trench is to be held for any length of time:—

(f) The sides must be revetted.

(g) The bottom of the trench must be floored.

The following points come next in order of importance:—

(a) The provision of good loopholes for snipers, at least one for each section of men in the trench.

(b) The construction or improvement of communication trenches; there should be one for each platoon from the from the support line to the front line trench, if possible.

(c) Listening posts, one for each platoon, pushed well ahead of the front line trench.

A good system of observation and sniping is of the utmost importance in trench warfare. Usually every battalion has a special detachment of trained snipers working under selective officers or non-commissioned officers. Their duties are to keep the enemy lines under constant observation, note any changes in the line, any new work undertaken by the enemy, keep the enemy snaipers in check and to inflict casualties on the enemy whenever opportunity offers.

During a reconnaissance patrol I stumbled across a sap, which, coming from the Boche lines, made me suspicious that there was something doing at the forward end. I followed the sap until I spotted a Boche sniper, who was luxuriously entrenched in a bullet proof cage. Coming from the rear, the sniper did not hear my approach, so he fell an easy victim. On searching the post I discovered a telescopic rifle, plenty of ammunition, food, beer and German literature.

Communications in the trench line are established by telephone, but it must be realized that in the event of heavy shelling all telephone communications is likely to be interrupted, and an efficient alternative system of orderlies—runners—must be arranged and tested.

Most of the honors fall to the lot of the runners, and I recall one of my own orderlies who for forty hours carried messages to and from a heavily shelled position where my men and I were fighting for our lives. The position in question had been captured and retaken about ten times.

It must be clearly understood that trench fighting is only a phase of operations and that the instruction in this subject, essential as it is, is only one branch of the training of troops. To gain a decisive success the enemy must be driven out of his defences and his armies crushed in the open. The aim of trench fighting, therefore, is to create a favourable situation for field operations, which the troops must be capable of turning to account.

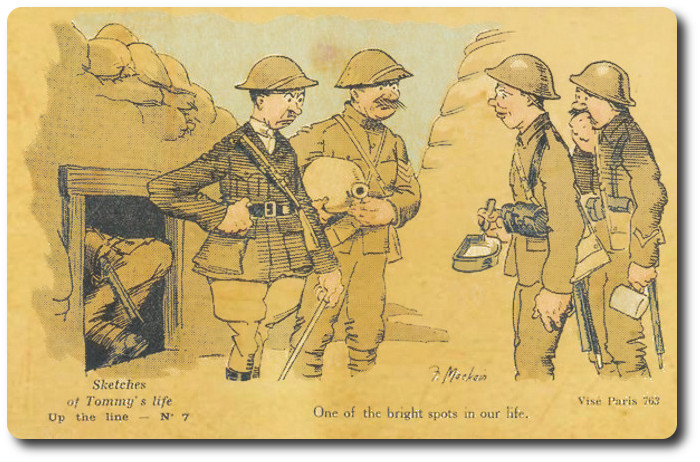

Although life in the trenches becomes very monotonous and dreary there is plenty of ground for humor, which relieves the nervous tension.

During these momentous times the thought of the soldier is:—"God for us all and every man for the side." the make audacity their battle cry, and these usually are the ones who return to relate the experiences of trench life.

Posted by regimentalrogue

at 12:01 AM EDT

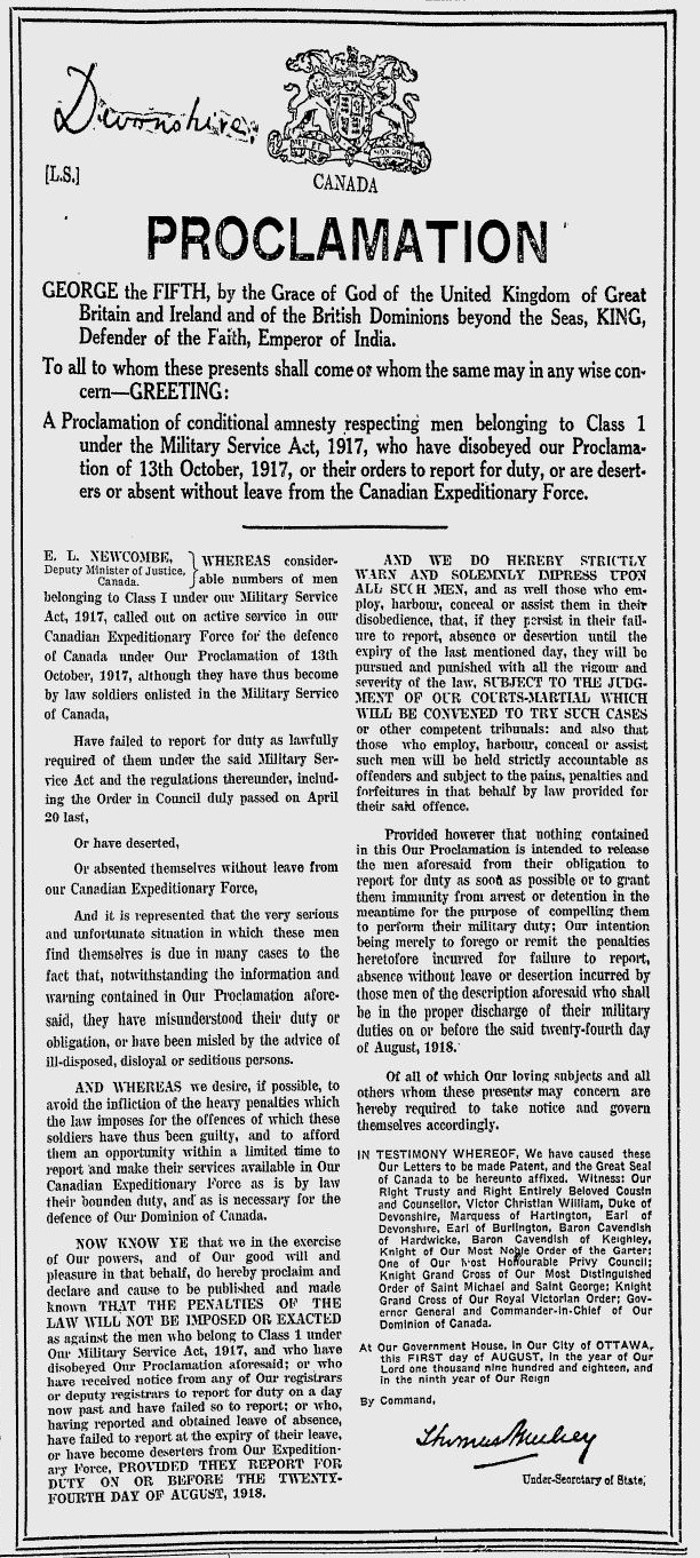

Reports from various parts of the country state that a larger percentage of native born Canadians are enlisting in the second contingent than went out with the first. In the first contingent it is said that only thirty per cent. of those who volunteered were native born Canadians, the remainder being British born, many of whom had some previous military training. Another factor noticeable in connection with the recruits for the second contingent is that they are a better type of men. The first contingent was largely made up of adventurers, while the recruits for the second contingent consist very largely of men holding responsible positions, who are throwing these up and going to the front from a sense of duty. Hundreds of college men will go out with the second contingent, while numbers of college professors from different universities have enlisted and are taking their places in the ranks. Business men from big corporations, banks, farmers' sons and others are vieing with one another in rallying to the call for men.

Reports from various parts of the country state that a larger percentage of native born Canadians are enlisting in the second contingent than went out with the first. In the first contingent it is said that only thirty per cent. of those who volunteered were native born Canadians, the remainder being British born, many of whom had some previous military training. Another factor noticeable in connection with the recruits for the second contingent is that they are a better type of men. The first contingent was largely made up of adventurers, while the recruits for the second contingent consist very largely of men holding responsible positions, who are throwing these up and going to the front from a sense of duty. Hundreds of college men will go out with the second contingent, while numbers of college professors from different universities have enlisted and are taking their places in the ranks. Business men from big corporations, banks, farmers' sons and others are vieing with one another in rallying to the call for men.

Rum as a Stimulant

Rum as a Stimulant

The occasion is the annual reunion of the survivors of the

The occasion is the annual reunion of the survivors of the