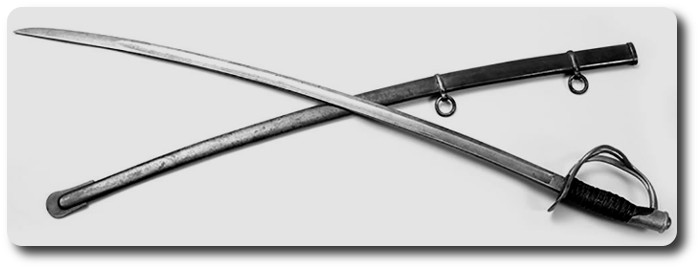

Topic: Cold Steel

Bayonets and Sabres (1878)

Boston Evening Transcript, 13 August 1878

[From the New York Times]

General Winfield Scott used to assert that such a thing as a bayonet wound inflicted in a charge was almost unheard of in his experience; and General Grant says in effect that in modern warfare "neither the sabre nor the bayonet is of use."

General Grant is reported to have said recently, at Berlin, to an officer in the German Army detailed to his suite, that he questioned very much whether in modern war the sabre of the bayonet was of use. "What I mean," said the general, "is this: Anything that adds to the burdens carried by the soldier is a weakness to the army. Every ounce he carries should tell in his efficiency. The bayonet is heavy, and if it were removed, or if its weight in food or ammunition were added to its place, the army would be stronger. As for the bayonet as a weapon, if soldiers come near enough to use it, they can do as much good with the club end of their muskets. The same is true as to sabres. I would take away the bayonet, and give the soldiers pistols in place of sabres. A sabre is always an awkward thing to carry."

The general had no doubt war showed instances when the bayonet was effective, but those instances were so few that he did not think that they would pay for the heavy burden imposed upon an army by the carrying of the bayonet. The German officer was not convinced by the general's reasoning, and said he "knew of cases where effective work had been done with the bayonet, and that the Prussians would not abandon it."

Now, he could hardly have read the statistical abstract, published in 1877, of the returns of killed and wounded on the German side in what is officially known as the "German Campaign in France," for where, in that great war, the bayonet killed its units and tens, the bullet destroyed its thousands and tens of thousands. Nor, comparatively speaking, were the wounds inflicted by cold steel severe. Three officers and eighteen men were killed by lance or bayonet, to a total of five hundred and seventy-four injured by those weapons. The most harmless, however, of all instruments of warfare would seem to be the sabre, which, in the furious charges of the valary regiments engaged at Sedan, and in all the battles of the war, killed but six men.

Great interest is being taken in many countries in this subject of "cold steel in time of war." and efforts are being made to prove the truth of falsity of the saying attributed to the humorous though ferocious Souvaroff, that "the bullet is a silly thing, but the bayonet firm and heroic."

In our own army the discussion was initiated by General Sherman, upon a recommendation of General Benet, chief of ordnance, that the bayonet and sabre shall cease for form part of the armament of troops. The general-in-chief called, not only for the views of officers of the line and staff who can speak as experts, and commanders whose men are thus armed, but also instructed Lieutenant Green, our military representative with the Russian Army in the late campaign, to make a special study of the question involved. So far as the views of our officers are concerned, a majority of them seem to be in favor of a retention of these time-honored weapons; but the theory of the minority is equally good argument for their abolition. Lieutenant Green, however, had excellent opportunities for proving the truth of the maxim of Napoleon, that "theory and practice are not the same thing in war." In the Turco-Russian was several instances occurred in which bodies of men closed with one another on the actual field of battle, and when, consequently, the bayonet was used, with more or less decisive effect. These hand-to-hand encounters were, it is true, never of very long duration, but while they lasted the fighting was exceedingly fierce. On more than one occasion, so it is reported, no quarter was either asked for or given after once bayonet had crossed bayonet; but official statistics may possibly disclose the fact that these sanguinary and stubborn contest were not more fatal than during the German campaign.

While the weight of evidence given by American officers is in favor of the retention of the sabre and bayonet, that of foreign officers is in the opposite direction. This is particularly true as regards the sabre. Colonel Dennison, in his prize essay on cavalry, goes so far as to pronounce the the sabre contemptible, and advocates a charge revolver in hand. An "English Cavalry Officer," in a work entitled "Notes on Cavalry tactics, Organization, etc.," is of opinion that the sabre of lance is the first weapon of the cavalry soldier; but he thinks firearms of some sort, in fact, indispensable. The Germans go beyond this. In a precis of an article from the Militair Wochenblatt, Colonel Ouvry says, "The view that the sabre is the arm which forms the essential characteristic of the cavalryman must, since the experiment of 1870-71, falls to the ground. The most complete independent action for cavalry must be the watchword in the future, and to aid this a good firearm must be supplied." We may add that in Germany even the lancers have a certain proportion of rifles in every squadron.

What is so much lost sight of in this kind of argument is the fact of the enormously increased value of firearms. The increased use of intrenchments on battle ground will, it is believed, tend to circumscribe the action of cavalry. The extreme range and rapid firing of the rifle and the increased power of the cross fire will, as a rule, enable the infantryman to hold his own, not only against horsemen in any formation and moving at any speed, but against infantry charges as well. But opportunities may occur in the best regulated battles, and, though they would suffer dreadfully in passing the zone of fire, the attacking party might, in a hand-to-hand fight, have their revenge. With a view, however, to such a chance, a cavalryman should be armed with a straight weapon, being the one best adapted for giving point, inasmuch as a cut is seldom deadly, while a thrust is generally so. As for "terror in a long line of glittering steel," or as to its not being "in human nature to stand and wait for bristling bayonets," there is perhaps a good deal of nonsense in such expressions. At any rate, the Confederate soldiers in front of Thomas at Chickamauga, and of Schofield at Resaca, were not so intimidated, much to the surprise, not to say disgust, of those who were trying hard to convince them that these charges were irresistible. The testimony on this subject of three great captains may be epitomized as follows: Napoleon, at St. Helena, said that he knew not "a single instance in which twenty pieces of cannons, judiciously placed and in battery, were ever carried by the bayonet"; General Winfield Scott used to assert that such a thing as a bayonet wound inflicted in a charge was almost unheard of in his experience; and General Grant says in effect that in modern warfare "neither the sabre nor the bayonet is of use." Such testimony as this should strengthen rather than weaken the recommendations made by the chief of ordnance. It is by no means unlikely that such fighting behind earthworks will have so large a place in warfare of the future, some armor covering for the head, neck, and perhaps arm, may be desired for infantry, in which event they will have to be relieved of much of the weight they now carry.

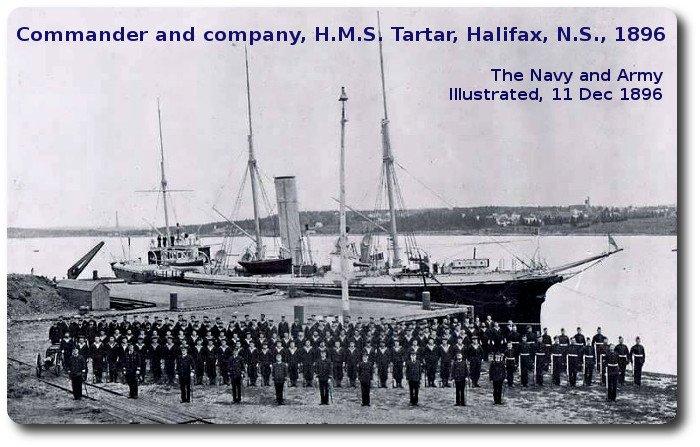

60. The officer commanding any military district or division, or the officer commanding any corps of active militia, may, upon any sudden emergency of invasion or insurrection, or imminent danger of either, call out the whole or any part of the militia within his command, until the pleasure of Her Majesty is known, and the militia so called out by their commanding officer shall immediately obey all such orders as he may give, and march to such place "within or without the district or division as he may direct."

60. The officer commanding any military district or division, or the officer commanding any corps of active militia, may, upon any sudden emergency of invasion or insurrection, or imminent danger of either, call out the whole or any part of the militia within his command, until the pleasure of Her Majesty is known, and the militia so called out by their commanding officer shall immediately obey all such orders as he may give, and march to such place "within or without the district or division as he may direct."

Col Hughes' Vagaries

Col Hughes' Vagaries

"For Valour" is the simple inscription for this most prized of all decorations, the Victoria Cross. Fashioned from a piece of bronze weighing but 434 grains, with an intrinsic value of tenpence, it stands as a means of rewarding individual officers and men of the army, navy and air force who might perform some signal act of Valour or devotion to their country in the presence of the enemy. Civilians of both sexes are eligible for its award under certain conditions. Generally the deed which won it is a condensed bald statement reading like a definition in a dictionary. These are always notified in the London "Gazette.' There are, however, many other incidents connected with its history that are not generally known.

"For Valour" is the simple inscription for this most prized of all decorations, the Victoria Cross. Fashioned from a piece of bronze weighing but 434 grains, with an intrinsic value of tenpence, it stands as a means of rewarding individual officers and men of the army, navy and air force who might perform some signal act of Valour or devotion to their country in the presence of the enemy. Civilians of both sexes are eligible for its award under certain conditions. Generally the deed which won it is a condensed bald statement reading like a definition in a dictionary. These are always notified in the London "Gazette.' There are, however, many other incidents connected with its history that are not generally known.

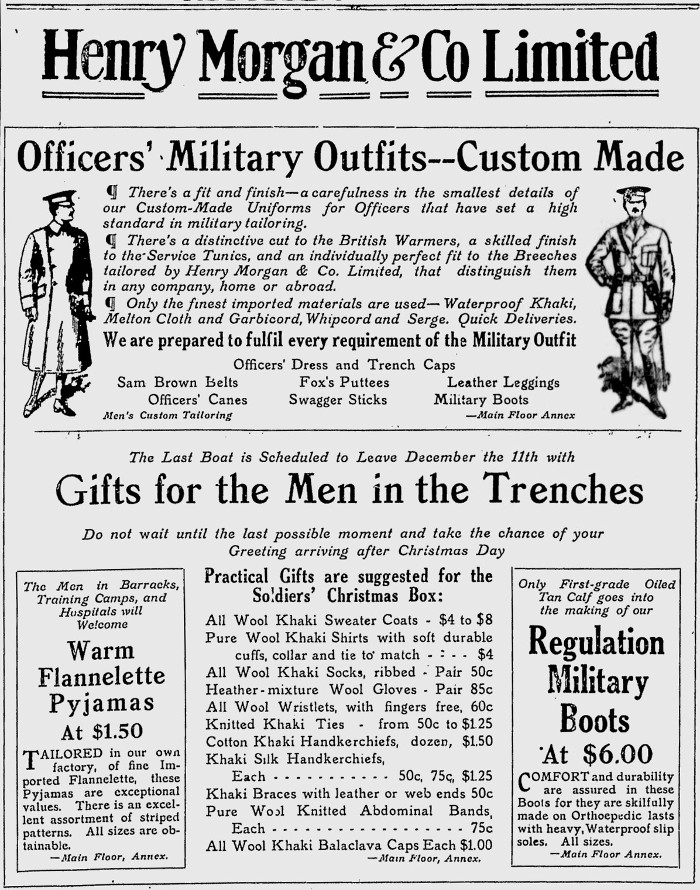

Ottawa, Sept. 13.—Ever since the publication of regulations respecting the presentation of the South African Medals, there has been dissatisfaction among the Ottawa men, who are entitled to this recognition. Many of the men are not now members of the militia, but a considerable number are still enrolled in the Ottawa regiments. A meeting was held last evening, at which both classes were represented, about 40 being present. It was then decided to disregard the regulations and parade to receive medals wearing khaki uniform. Their decision soon reached the ear of the military authorities, as a result which the following order was promulgated today:

Ottawa, Sept. 13.—Ever since the publication of regulations respecting the presentation of the South African Medals, there has been dissatisfaction among the Ottawa men, who are entitled to this recognition. Many of the men are not now members of the militia, but a considerable number are still enrolled in the Ottawa regiments. A meeting was held last evening, at which both classes were represented, about 40 being present. It was then decided to disregard the regulations and parade to receive medals wearing khaki uniform. Their decision soon reached the ear of the military authorities, as a result which the following order was promulgated today:

After the ceremony has been performed and the couple start to leave, the ushers draw their sabers—or swords for navy—at the command "Draw Sabers" (from one of the ushers) at the foot of the chancel steps and the bride and bridegroom pass beneath the arch. After they have passed through the ushers each take a bridesmaid down the aisle and out of the church. In marching out of the church, the bridegroom, best man and ushers offer their right arms to the bride, maid-of-honor and bridesmaids, thus avoiding entanglement of sabres or swords and dresses, and leaving the left hand free to carry the cap.

After the ceremony has been performed and the couple start to leave, the ushers draw their sabers—or swords for navy—at the command "Draw Sabers" (from one of the ushers) at the foot of the chancel steps and the bride and bridegroom pass beneath the arch. After they have passed through the ushers each take a bridesmaid down the aisle and out of the church. In marching out of the church, the bridegroom, best man and ushers offer their right arms to the bride, maid-of-honor and bridesmaids, thus avoiding entanglement of sabres or swords and dresses, and leaving the left hand free to carry the cap.