Topic: CEF

Life in the Trenches

The British Soldier: His Courage and Humour, Rev. E.J. Hardy, M.A., 1915

Although this article isn't specifically about the CEF, it has been tagged as such to keep it with other First World War material.

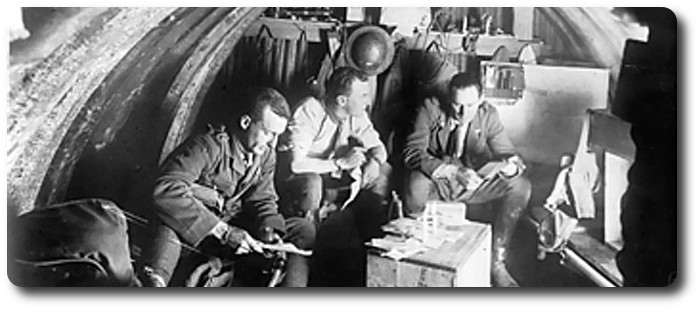

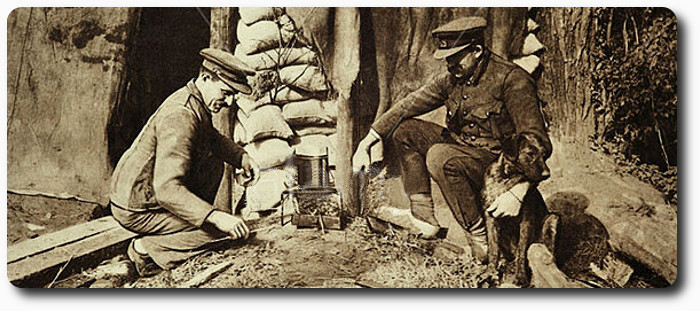

A Scottish Borderer described life in the trenches in the following extract from a letter: "To kill time we played banker with cigarette cards. We become rather like schoolboys over food. One of our mess had a small tin of biscuits sent through the post yesterday we all crowed over it just like youngsters. One's joys are of the primitive type; when, like our ancestors, we turn to live in the fields and woods again. A padre turned up yesterday, and at night (it was not safe to begin earlier) we held a service at which a great number of our men attended. We are a light-hearted lot and so are our officers. We dug out for them a kind of a subterranean mess-room where they took their meals. One fellow decorated it with a few cigarette cards and some pictures he had cut out of a French paper. Their grub was not exactly what they would get at the Cecil. A jollier and kinder lot of officers you would not meet in a day's march. One officer who was well stocked with cigarettes divided them among his men, and we were able to repay him for his kindness by digging him out from his mess-room. A number of shells tore up the turf, and the roof and sides collapsed like a castle built of cards, burying him and two others. They were in a nice pickle, but we got them out safe and sound. There are apple trees over our trench, and we have to wait till the Germans knock them down for us. You ought to see us scramble down our holes when we hear a shell coming."

The experience of ten days in the trenches was thus described:

"We dig ourselves deeper and deeper into the earth, till we are completely sheltered from above, coming out now and then, when things are quiet, to cook and eat, making any moves that may be necessary under cover of darkness. Ammunition, food, and drinking water are brought in by night; the wounded are sent away to the hospital.

We do not wash, we do not change our clothes we sleep at odd intervals whenever we can get the chance, and daily we get more accustomed to our lot. It is rather an odd existence. Little holes dug beneath the parapet just big enough to sit in are our homes, with straw and perhaps a sack or two for warmth. The cold is intense at night, and those good ladies who have made us woollen caps and comforters have earned our thanks; also, we are getting used to it. The coldest moments are those when there is an alarm of a night attack, and we spring from our sleep to stand shivering behind the parapet peering over the wall to see our enemies, and firing at the flashes of their rifles. It is exciting. Every time you put as much as your little finger over a trench there is a hail of bullets."

A regiment was in trenches under fire and returning it. Two privates noticed that the French interpreter was placed at a spot where the trench was not wide enough to enable him to make proper use of his rifle. "The Frenchman isn't comfortable," said one, and both left the trench, spade in hand, knowing well that they were serving the enemy as targets, dug out the trench in front of their French comrade, and returned with unbroken calm to their own places and their rifles.

There was a humorous attempt to be homelike. A sergeant-major by the name of Kenilworth put outside his bivouac "Kenilworth Lodge. Trades-men's entrance at the back. Beware of the dog." The dog was picked up at Rouen.

Other shelters were named Hotel Cecil, Ritz Hotel, Billet Doux, Villa De Dug Out, etc. Soldiers called the ordinary trenches, "Little wet homes in a sewer."

Modern research shows that there is no single trait which consistently differentiates leaders from followers, except perhaps intelligence, so how do you differentiate between leaders and followers? This trait concept is perhaps best summarized by

Modern research shows that there is no single trait which consistently differentiates leaders from followers, except perhaps intelligence, so how do you differentiate between leaders and followers? This trait concept is perhaps best summarized by

The war in Vietnam is a small unit leader's war. Because of the large number of semi-independent platoon and company missions performed by units in Vietnam, the knowledge and skill of the small unit leader are more important than ever before. Some of the lessons learned by small unit commanders are discussed below.

The war in Vietnam is a small unit leader's war. Because of the large number of semi-independent platoon and company missions performed by units in Vietnam, the knowledge and skill of the small unit leader are more important than ever before. Some of the lessons learned by small unit commanders are discussed below.

Inherent in Mao Zedong's military writings are numerous strategic and tactical principles, many having a strong emphasis on politics. These principles, although not adhered to as rigidly as they were before Mao's death, as generally used in both planning and operation.

Inherent in Mao Zedong's military writings are numerous strategic and tactical principles, many having a strong emphasis on politics. These principles, although not adhered to as rigidly as they were before Mao's death, as generally used in both planning and operation.

On Friday 30-11-18, at 10.45 hours a class was organised of those who could neither read or write, a teacher appointed and instruction begun.

On Friday 30-11-18, at 10.45 hours a class was organised of those who could neither read or write, a teacher appointed and instruction begun.

"We have some daring ladies from

"We have some daring ladies from

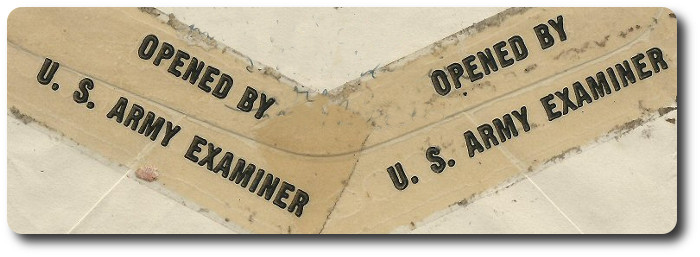

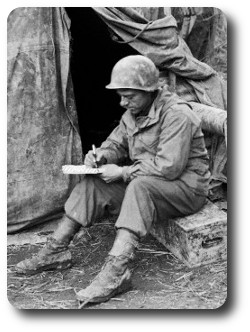

In order not to waste time in the actual writing of letters, knowing what you can't say is a help. Twenty taboos, based on European Theatre of Operations (ETO) circulars, should be borne in mind:

In order not to waste time in the actual writing of letters, knowing what you can't say is a help. Twenty taboos, based on European Theatre of Operations (ETO) circulars, should be borne in mind:

British Daily Ration, 1914:

British Daily Ration, 1914:

My leadership philosophy is very, very simple. It can be summed up in three basic points. First, if we empower people to do what is legally and morally right, there is no limit to the good we can accomplish. That is all I ask of anyone: Do what is right. Leaders must look to their soldiers and focus on the good. No soldier wakes up in the morning and says, "Okay, how am I going to screw this up today?" Soldiers want to do good and commanders should give them that opportunity. An outstanding soldier, Command Sergeant Major Richard Cayton, the former

My leadership philosophy is very, very simple. It can be summed up in three basic points. First, if we empower people to do what is legally and morally right, there is no limit to the good we can accomplish. That is all I ask of anyone: Do what is right. Leaders must look to their soldiers and focus on the good. No soldier wakes up in the morning and says, "Okay, how am I going to screw this up today?" Soldiers want to do good and commanders should give them that opportunity. An outstanding soldier, Command Sergeant Major Richard Cayton, the former

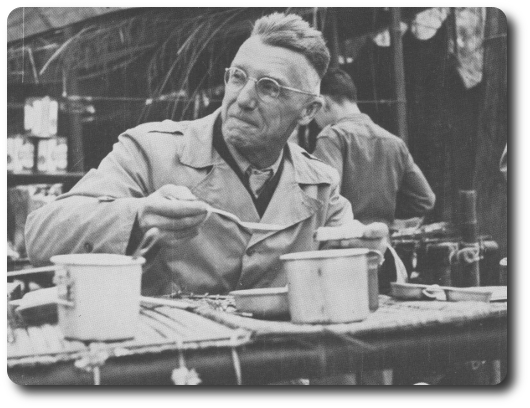

John Lord went on to describe the moving circumstances in which Ray Sheriff arrived at Stalag XIB, a memory always recalled by him with great emotional strain.

John Lord went on to describe the moving circumstances in which Ray Sheriff arrived at Stalag XIB, a memory always recalled by him with great emotional strain.