Honours and Awards

Topic: Medals

Honours and Awards

Battle Dress, by Gun Buster

Later, I shall come to the incident itself in which Lieutenant Reginald Ellington of the 666th Field Regiment R.A. figured as hero.

Hero is the word understood of, and approved by thc general public. But it is not the term under which Reggie Ellington's comrades ever consider him. And, of course, it is the very last word he would dream of in connection with himself.

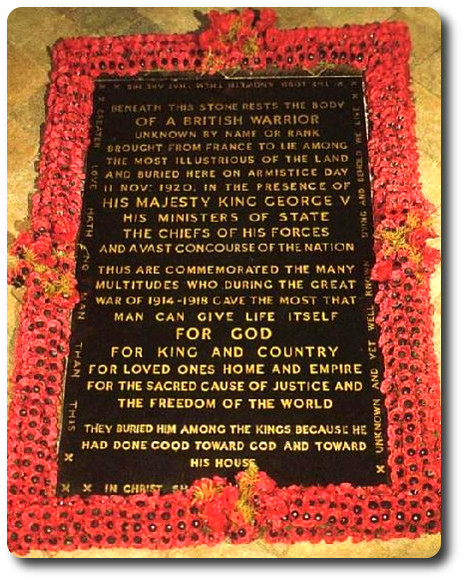

Upon this subject of gallant deeds and decorations there is a noteworthy difference of thought between the population of the Army itself and what may be called their civilian relatives—in other words, the outside public. It may be accepted as a truth beyond contradiction that the Army knows all there is to be known about decorations, their worth, their significance, and sometimes their insignificance. They have standards and appreciations that are not always identical with those held outside its ranks. The generous-minded, sentimental public love to have their heroes. They take them to their heart and glamourise them. But to the people within the Army there is no glamour about a medal. Even a V.C.—which takes a bit of winning—does not carry hero-worship with it. This, of course, must not be taken to mean that the Army does not care for decorations just as much as everybody else. The Army does But it is very reluctant to regard them as a badge of superhuman courage or ability, by which one man is to be for ever distinguished beyond his fellows. They like decorations in the Army, but they like them mainly as an indication that a job of work has been well done. The only possible exception to this is to be found in the case of the V.C. to win which a man must face almost certain death. It is recognised that here is something a bit more out of the way than a "job of work." It is also recognised that a man will do things in the heat of battle that in cold blood would make him sick merely to think about. So the soft-pedal comes down on the hero-worship, even with the V.C.

The Army nurtures no illusions about "gongs," their own expressive slang for medals. They know that the man disporting one is as likely to be no braver than the man without. They know that many factors have to fall just right for the winning of one. And they know that a principal factor is luck. All may be brave, but not all may be lucky enough to have their deeds noticed. A man may miss a V.C. merely because his gallant behaviour happens not to be seen by "someone in authority"—an essential condition. Opportunity is another potent factor. One man may go through a long campaign and never a chance of qualifying for a "gong" comes within a mile of him. Another has opportunities thrust upon him in his very first engagement. He simply cannot miss them. There still remains the mystery of the final adjudication—how one bit of work comes to be acknowledged by the powers that be as worth an M.C. or an M.M. while another, to all intents and purposes just as meritorious, goes unrewarded. Illustrative of this is the story of a gunner subaltern in the last war, who was recommended on four different occasions for the M.C. but never received more than a "mention in despatches." He was recommended a fifth time, and got it. Ultimate recognition came to him because in the middle of an action he had thrown a bucket of water over the hessian camouflage net covering a gun-pit, after it had been set on fire by the flash from one of the guns. The deed involved him in no particular danger. He happened to be standing near a bucket at the time, and acted with presence of mind. That was all. As a "gong-earner" the exploit could not be compared with any of the previous four that had not been considered worthy of the M.C. The subaltern knew it, and was always very shy of his belated ribbon. It is the complete understanding of these fortuitous factors governing decorations that gives the Army its very clear perspective on the subject.

The Army divides all D.S.O.'s, M.C.'s, M.M.'s and D.C.M.'s into two distinct classes. The first are known as "Immediate Awards," and they are given for gallantry or distinguished conduct in action. Your recommendation for one of these goes in from the Regiment to the Division directly the action is over. Sometimes this will be the same day. The C.O. may make it his last job that night. There is as little delay as possible. Hence the term: "Immediate Awards."

The second group are familiarly known in the Army as "Ration Honours," and though the "high ups" may be slightly- shocked by the irreverence of the phrase, nevertheless it very neatly sums up their character. They come along automatically, like rations, after an action in which a Division or more has been engaged. It may be one, two, or three months after. But they arrive. So many D.S.O.'s, so many M.C.'s, so many M.M.'s and D.C.M.'s for each Division. These in turn are cut up and allotted to each regiment that took part in the action. If, as often happens, there are no outstanding cases of gallantry still deserving recognition, the C.O. of the regiment or battalion holds a conference with the Majors to decide who shall receive them for general good work. Much like the distribution of good conduct medals at school.

Therefore, it will easily be understood that a D.S.O., M.C., M.M. or D.C.M. may mean many different things. If it be an "Immediate Award" it implies a good deal more than if it be a "Ration Honour." Generally speaking, "Immediate Awards" are individually earned honours. A Colonel or Major may get a D.S.O. simply because his battalion or regiment, or company or battery, has been doing well. They cannot get less, because the M.C. is not awarded to anyone over the rank of captain. On the other hand, a D.S.O. can be won by a subaltern and, speaking generally again, if a subaltern gets the D.S.O. you can bet your boots that it is worth far more than the majority of D.S.O.'s handed out to Colonels and Majors. A subaltern's D.S.O. is never a "Ration Honour." It's more likely to be a near-miss to a V.C.

Perhaps it is because the Army knows so much of the "inside story" of decorations that the subject is never a popular one for conversation among officers or men. If the topic does crop up it is mentioned in a very diffident manner, and the talk soon dies a natural death. The last man in the world to tell you how he won a "gong" is the wearer of the ribbon himself. (I am speaking, of course, as in the Army. Among his civilian friends he may feel less embarrassed.) Most of them wear their new ribbons almost apologetically. "You'd have done the same if you'd been in my position," sums up the whole medal attitude. They can also be very touchy on the subject amongst their comrades. I recall a young gunner subaltern who, after being evacuated from Dunkirk, went home on leave, and the morning after saw to his horror that the newspapers had made a headline story of his winning the M.C. He felt so embarrassed that when he rejoined the regiment six days later he still hadn't put up the ribbon.

"Why aren't you wearing it?" asked the Colonel.

"I'm very annoyed about the whole affair, sir" he replied. "I hope none of you think I had anything to do with that newspaper stuff."

"My dear fellow, we never dreamed for a moment that you had," said the Colonel. "Let me see you with that ribbon on to-morrow. That's an order."

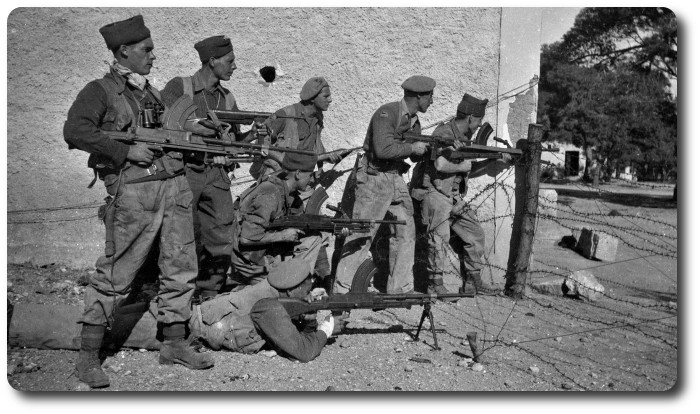

Having seen a good many "gongs" cleaned up by the B.E.F. in Flanders and France I am able, without hesitation, to add my testimony to the bulk of evidence supporting the theory that there exists no specific "brave man" type. A lot of preconceived ideas about who would do well and who wouldn't went by the board as soon as men came under fire. Some of the frail looking rabbits did magnificently. Some of the great hefty fellows, real bruisers, turned out hopeless. And it was the same with temperament as with physique. Which only goes to show that human nature is as incalculable on the battlefield as it is elsewhere.

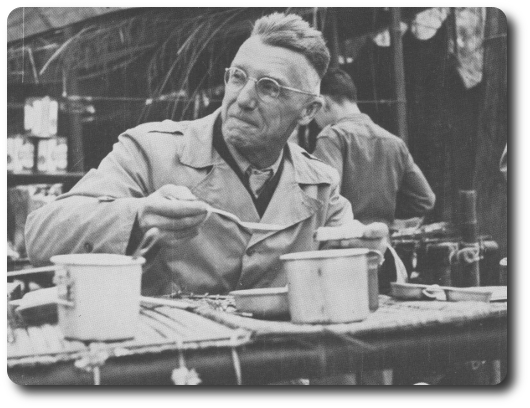

And this brings me back to Lieutenant Reggie Ellington, whose externals were not of the type usually associated with candidates for battlefield honours. Reggie had the pallor of a lily. He was frail, and somewhat drooping. If he represented any type at all, it was the youthful man-about-town, dandified, and a bit affected. Later on, we were to remember that if Reggie exhibited the paleness of the lily, he also possessed its coolness. We remembered occasions when he had talked to brass-hats as if he were doing them a favour. (Surprisingly enough, they'd take it from him.) Winning an M.C. would come as child's play to a youth who could do this, we realised. But this was only wisdom after the event. So was our realisation that his treatment of serious matters as a joke, and his apparent lack of any sense, of responsibility, had all the time been merely a pose. Before the war, Reggie had "been something" in his father's business in the City. He affected to find army life unendurable without his portable wireless set, and his cigar in the evening. Wherever he was, and whatever the critical conditions during the Retreat, he never missed his cigar. Whatever else had to be jettisoned, he clung to his cigar box and wireless set to the grim end. And it was grim enough, in all conscience. Dunkirk beach, strewn with its dead and dying, a pall of smoke blotting out the sky, the promenade one sheet of flame, the German shells bursting among the dunes, the dive-bombers distributing their final dose of death and destruction before nightfall. And in the middle of the horrors, Reggie Ellington seated calmly on the sand in front of his crooning wireless, smoking his very last cigar. Just one man of many who, in the hectic days of the preceding three weeks, had done a good job of work.

Posted by regimentalrogue

at 12:01 AM EDT

Inherent in Mao Zedong's military writings are numerous strategic and tactical principles, many having a strong emphasis on politics. These principles, although not adhered to as rigidly as they were before Mao's death, as generally used in both planning and operation.

Inherent in Mao Zedong's military writings are numerous strategic and tactical principles, many having a strong emphasis on politics. These principles, although not adhered to as rigidly as they were before Mao's death, as generally used in both planning and operation.

On Friday 30-11-18, at 10.45 hours a class was organised of those who could neither read or write, a teacher appointed and instruction begun.

On Friday 30-11-18, at 10.45 hours a class was organised of those who could neither read or write, a teacher appointed and instruction begun.

"We have some daring ladies from

"We have some daring ladies from

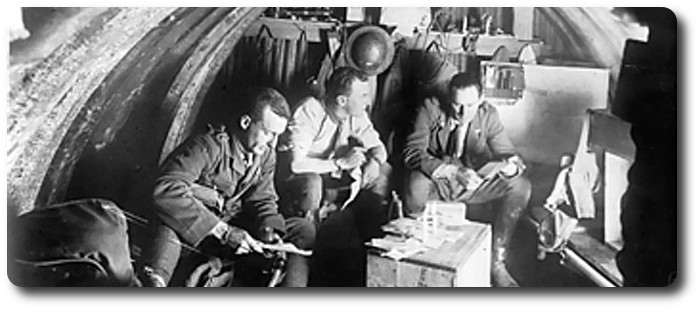

In order not to waste time in the actual writing of letters, knowing what you can't say is a help. Twenty taboos, based on European Theatre of Operations (ETO) circulars, should be borne in mind:

In order not to waste time in the actual writing of letters, knowing what you can't say is a help. Twenty taboos, based on European Theatre of Operations (ETO) circulars, should be borne in mind:

British Daily Ration, 1914:

British Daily Ration, 1914:

My leadership philosophy is very, very simple. It can be summed up in three basic points. First, if we empower people to do what is legally and morally right, there is no limit to the good we can accomplish. That is all I ask of anyone: Do what is right. Leaders must look to their soldiers and focus on the good. No soldier wakes up in the morning and says, "Okay, how am I going to screw this up today?" Soldiers want to do good and commanders should give them that opportunity. An outstanding soldier, Command Sergeant Major Richard Cayton, the former

My leadership philosophy is very, very simple. It can be summed up in three basic points. First, if we empower people to do what is legally and morally right, there is no limit to the good we can accomplish. That is all I ask of anyone: Do what is right. Leaders must look to their soldiers and focus on the good. No soldier wakes up in the morning and says, "Okay, how am I going to screw this up today?" Soldiers want to do good and commanders should give them that opportunity. An outstanding soldier, Command Sergeant Major Richard Cayton, the former

John Lord went on to describe the moving circumstances in which Ray Sheriff arrived at Stalag XIB, a memory always recalled by him with great emotional strain.

John Lord went on to describe the moving circumstances in which Ray Sheriff arrived at Stalag XIB, a memory always recalled by him with great emotional strain.

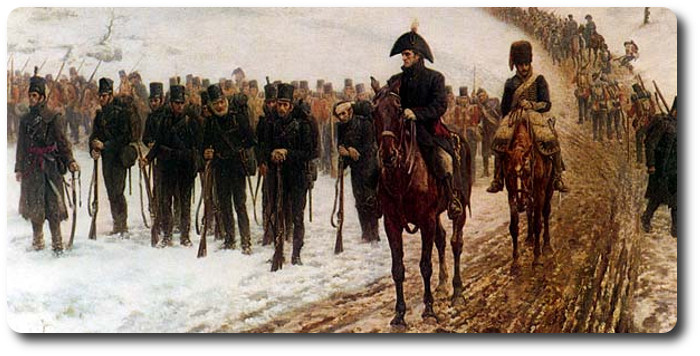

The army of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, moreover, contained ruffians whose excesses in the field could best be repressed by the lash, if only to save them from the gallows; accordingly the cat was accepted by the troops almost as a necessary part of the hardships of war. So there comes to mind a vision of

The army of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, moreover, contained ruffians whose excesses in the field could best be repressed by the lash, if only to save them from the gallows; accordingly the cat was accepted by the troops almost as a necessary part of the hardships of war. So there comes to mind a vision of