Feeding an Army 1903

Topic: Army Rations

The standard vehicle for the movement of ammunition, engineer stores, food, and fodder was the General Service Waggon.

Feeding an Army

The problem in the Manoeuvres at Aldershot

South African Lessons

Soldier Learned Quite a Lot in His Years of Actual Experience of Living in the Field

The Gazette, Montreal, 17 October, 1903

(Special Correspondent, London Telegraph)

There is an impression among some people that a British soldier can carry enough food with him to last a week; but, unfortunately, no ground exists for the belief, despite the progress which has been made in the art of compressing nourishment, both solid and liquid, into a minimum of space. Apart from the questions of strategy, tactics, and the individual training of the soldier to the conditions of field service, the army manoeuvres are expected to tFeeding an Army 1903each some valuable lessons regarding the supply of necessaries and transport, two considerations which enter so largely into every problem of war. It is a true saying that a "soldier marches upon his stomach," and his fighting power depends upon the prompt arrival of bread and meat, as well as ammunition, from his base of supply. A portion may travel by train, but the regimental transport by road is the service upon which he must usually rely when operating in an enemy's country. In the case of the First Army Corps, which has just taken the field, the base of supply is Aldershot, to which a force of nearly 20,000 men must now look for the supply of their daily wants, and it will be the duty of the Army Service Corps to see that every unit of that force is provisioned, no matter to what part of the manoeuvre area of 1,600 square miles the soldiers may be called or driven by the fortunes of war. It is possible in real war to "feed your troops on the country" or to billet them upon the population; but in this September campaign, Tommy Atkins must rely upon his friends at Aldershot and some miles of wagon transport.

The manoeuvre ration is fairly liberal. It consists of five big biscuits and 2 1/2 ounces of Canadian cheese, carried in the haversack. In addition to bread and meat of excellent quality, sent from Aldershot, the soldier is allowed the following quantities per day.—Tea, 1/3 ounce; coffee, 1/3 ounce; sugar, 2 ounces; pepper, 1/32 ounce; salt, 1/2 ounce; condensed milk (1 tin to 20 men), 4/5 ounce; jam, 4 ounces; or if procurable, potatoes or other fresh vegetables, 8 ounces; bacon or German sausage (breakfast), 4 ounces.

Daily Fuel Allowance

To cook the foregoing an allowance of two pounds of fuel wood per man is made daily, or on the alternative one pound of coal, with one pound of kindling wood to every twenty pounds of coal. No less than 240,000 rations, consisting of the above items, were ordered for the manoeuvres of the First Army Corps alone, based on the assumption that provisions for twelve days was to be made for 20,000 men. It is estimated that a large proportion of the sum of £200,000 which the manoeuvres of the two army corps are supposed to entail will be expenses on these supplies, and a still larger sum will be swallowed up by transport to the fighting line. There will be a considerable excess of rations packed up at Aldershot and ready for travel which will not be required, seeing that Sir John French's force is less than 20,000, and that the men will be back in barracks within ten days at the most. Apart from the expense of surplus packing, however, no loss will be sustained, and the authorities will recoup themselves for Tommy's grocery bill by the somewhat drastic measure of deducting 3 1/2 d per day from his wage!

Meat and bread for the soldier are issued from the butchers and bakers of the Army Service Corps at Aldershot, but the remaining items are supplied by civilian contractors. The latter commenced work some weeks ago in two small tents at the base, whence they removed as stores accumulated to a spacious drill hall. I had the advantage of seeing and tasting the groceries, and can guarantee that the samples were excellent. They were packed in brown paper parcels suitable for messes of five, ten, twenty, and fifty men, and these parcels were encased in strong wooden boxes, which will bear the jolting of the regimental waggon. Some boxes contained only 250 parcels, and other as many as 1,000, according to the requirements of the unit for which they are intended. Messrs. R. Dickenson & Co., the army contractors, describe the bacon as smoked rolled shoulders, and the cheese as best Canadian, while the jam has been specially prepared in scaled tins. Each cheese weighs 80 pounds, and, like bacon, biscuit, and jam, is distributed to the troops not in parcels, but "in bulk," according to requirements. A man-of-war's-man with such a daily ration would deem himself lapped in luxury, but the sailor is taken in hand by his country much earlier than the soldier, and consequently is trained to a diet when at sea which would rather stagger Mr. Atkins. In one respect, however, the bluejacket fares better; he has a daily allowance of one-eighth of a pint of rum, mixed with two-thirds of water. The soldier, except on active service, enjoys no such concession, though his is allowed to buy during the manoeuvres as much as two pints of beer per day.

The rations having been prepared, we come to the task of forwarding and distributing them. For this work the Army Service Corps, one of the few departments which emerged with credit from the war enquiry, has made special preparations. The troops under Sir John French left Aldershot with two days' supplies carried in the transport waggons, and later the "supply park," or magazine, left for the front with a reserve.

The Beginning of Manoeuvres

With the commencement of the manoeuvres the supply proceeds under army corps arrangements and comes under the direct orders of the general officer commanding. The "supply park"—a square formed of waggons—is the distributing centre for the troops, and is kept replenished by other waggons, which proceed either to and from the base at Aldershot or to the nearest railways station, where bread and meat, dispatched in special train by London and Southwestern railway, are received daily. In addition to the rations for the troops, supplies of ammunition for the guns and forage for the horses, distributed over a very large and scattered area, must be maintained every day, a feat which accounts for the employment of a small army of civilian drivers and a large number of subsidized horses. The maximum load of the general service waggon is 2,600 pounds and two horses will generally suffice. In South Africa our supply waggons often carried 7,000 pounds weight of goods, drawn by thirty or more oxen, and the pace barely exceeded two miles per hour. The waggons of the First Army Corps, travelling over the high roads of the middle southern counties with no dongas and rough country to interrupt their progress, do much better.

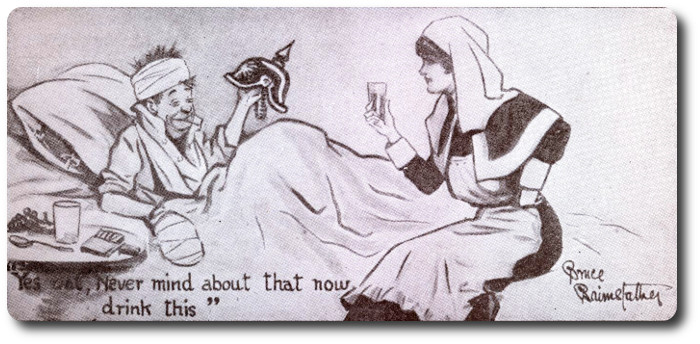

It must be confessed that the South African experience developed for making the soldier's capacity for making the most of his raw materials. The meat from Aldershot may be cooked, as usual, with the primitive appliances of a "field kitchen" and fire trench, but the bully-beef and biscuit exact more careful treatment. Mr. Atkins can improve both. He has a mess tin which serves alternately as a saucepan, frying pan, and teapot. The bully-beef is made quite tasty for a hungry soldier when stewed with a few vegetables, which can be found throughout the manoeuvring area, and the biscuits when boiled with the condensed milk and sugar take the place of pudding. Experiments are to be made with a new patent oven, of which great things are expected, also with a water sterilizer apparatus, which is to be tried for the first time. In South Africa the field service ovens often lost their way, but the soldier found that a large anthill when scooped hollow and an aperture made for draught, answered as well. I have eaten bread made of two parts flour and one of bran, cooked in such ingenious fashion, by the British soldier, which I prefer to the regimental biscuit, as more tasty and digestive. The regimental biscuit, to speak frankly, is often a tooth-destroying, temper-provoking diet, which may be tolerated on active service, but should only form the emergency diet at manoeuvre times. I have not tasted the biscuit of the First Army Corps, but am told it is vastly superior to that with which South African campaigners are familiar.

Posted by regimentalrogue

at 12:01 AM EST

Wide World Feature

Wide World Feature

Ottawa Citizen, 18 Dec 1931

Ottawa Citizen, 18 Dec 1931

The Daily Mail and Empire; Toronto, 19 October 1899

The Daily Mail and Empire; Toronto, 19 October 1899

Non-commissioned officers and men serving in the R.C.R.I. and R.C.A. (garrison division) who wish to volunteer for special services in South Africa will send their names to the officer commanding their company, who will have them medically inspected. The names of men passed as fit will be at once communicated by the officers commanding companies to Lieut.-Col. Otter, Toronto, who will allot them to the companies of the special service force according to his judgment.

Non-commissioned officers and men serving in the R.C.R.I. and R.C.A. (garrison division) who wish to volunteer for special services in South Africa will send their names to the officer commanding their company, who will have them medically inspected. The names of men passed as fit will be at once communicated by the officers commanding companies to Lieut.-Col. Otter, Toronto, who will allot them to the companies of the special service force according to his judgment. Another order issued to-night states that a grant of $125 will be given to officers of the force towards defraying expenses of outfit. An advance of pay to the amount of $60 will also be allowed. Cheques for these amounts will be forwarded.

Another order issued to-night states that a grant of $125 will be given to officers of the force towards defraying expenses of outfit. An advance of pay to the amount of $60 will also be allowed. Cheques for these amounts will be forwarded. The Officers

The Officers

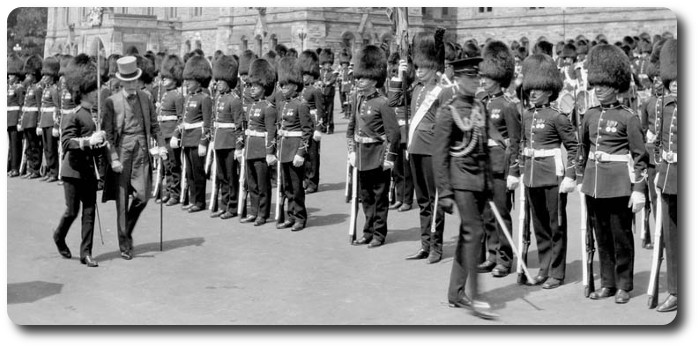

Ottawa Citizen; 2 July 1941

Ottawa Citizen; 2 July 1941 Brilliant color and stirring martial music was provided by the Royal Marines Band.

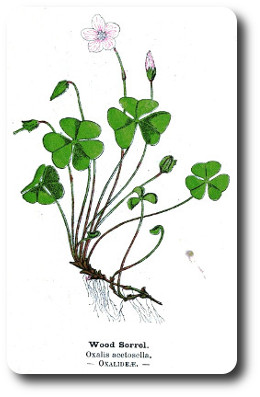

Brilliant color and stirring martial music was provided by the Royal Marines Band. Presents Sorrel

Presents Sorrel

Heading the supplementary list is a the

Heading the supplementary list is a the

With the Canadians in Sicily, Aug. 31,—(CP)—Canada's P.B.I. (poor bloody infantry) came through with the goods in the

With the Canadians in Sicily, Aug. 31,—(CP)—Canada's P.B.I. (poor bloody infantry) came through with the goods in the  The most spectacular infantry exploit was probably the storming of the Assoro cliffs by the

The most spectacular infantry exploit was probably the storming of the Assoro cliffs by the