Unwritten Rules

Topic: Forays in Fiction

Unwritten Rules

By: Michael O'Leary

Matt runs his fingers through his hair, trying to get that devil-may-care look with the short cropped strands, the gel he once used liberally now hardly discernible, even to the touch. He breathes in deeply, at least this time no-one will be trying to make him buy drinks for being "out of dress."

Inhaling again, he deliberately "sucked in his stomach, stuck out his chest." The black vest hugs his abdomen, the pants fit well around his ass—no doubt the girls will notice that later—and the red jacket, finely tailored, fits like a glove. Have the tailor measure your dad, they said. You'll grow into it, they said. You won't need to buy a new one as soon, they said. 'Fuck them,' Matt thinks, 'I look good in this.'

He is barely comfortable wearing the oxford shoes, jacket and tie ensemble of his dress uniform. In comparison, the tight straight-leg pants, waistcoat and jacket of the Mess Dress—for official dinners in the Officers' Mess—is an almost surreal departure from the jeans and t-shirts he wore almost exclusively before he joined the Army. Matt despises Mess Dinners—long hours surrounded by starchy and boring older officers—dinners more endured than experienced—but afterwards, Matt knows his red jacket will stand out in the local bars, like a flame to the already tipsy moths from the sororities. It's the only time he can get away with wearing it downtown.

Half remembered snippets from an antiquated "Guidance for Young Officers" and other dreary advice filter thorough Matt's mind. Don't talk of women, religion or politics. Light drinks before dinner. Subalterns should treat their seniors as they would a rich uncle from whom they have expectations—what the fuck does that even mean?

'To hell with it.' he thinks. Pulling open the cloak room door, Matt streps through towards the bar. He nods to three peers already in the lounge with drinks, still in issued uniforms and not yet the privately purchased Mess Kit he notes, and then on into the bar room itself.

Matt subconsciously half halts, his mind whirls to recall that he has checked every detail of his uniform. He is sure of it. 'Let them look, they never wore it this well,' he thinks. He pushes his way through to the bar, past more senior officers, some he'd never seen before.

Who is that Major lecturing the Commanding Officer with one pointed finger, a sloshing scotch in his other hand. Surely he will be taken to task. Matt can't believe his ears when some old Captain addresses the Brigade Commander, a General, by his first name.

His ears capture snippets of conversations.

The Major, slurring, already, before dinner: "… I'll tell you Colonel, you were one of the better young officers I trained, but …"

The Captain, his precise elocution failing to hide his burning emotions: "…I tell you Bob, there's no good way to manage that affair, you've got to push the regimental plan, and damn the Army …"

An anonymous voice, obviously not schooled in "Guidance for Young Officers" rings clear: "I met her in church, noticed her when I was sorting out that NDP-loving husband of hers, and she invited me over for tea when he wasn't at home. I tell you, she sure serves some interesting sweets with her tea."

Matt finally squeezes through the crush of pre-dinner meeting and greeting, placing himself tight against the edge of the polished wood bar in the one small accessible gap. Looking left and right, he notes the usual pair of officers manning the bar ends like alcoholic sentries posted there for the pre-dinner gathering. They are "the gargoyles," as the subalterns have labeled them. To the left, an ancient Major who looks like he truly believes subalterns should be seldom seen and never heard. To the right, a burly Captain, reputed to be a beast when training officers and an even greater beast when drunk at Mess Dinners. 'Please God,' thinks Matt, who only invokes the deity at such crucial moments, 'may I not be sitting near to either of them this time.'

Having caught the bartender's eye, uncharacteristically but according to seldom followed protocol, Matt orders a sherry. "Light or dark?"—'How the fuck would I know?'—"Uh, light."

The dainty glass arrives. 'Shit, I'm not walking into the lounge carrying that,' he thinks. "And a draft," he blurts before he had lost the steward's attention. The sherry disappears as a quickly downed shot while the beer foams into the glass from the tap.

Back through the crush, with only one boot heel scraping across the toe of his right Quarter Wellington boot, brand new and now duly christened. Matt joins the other subalterns in the lounge. It's a reversal of norms. The subalterns would usually be the louder crew in the bar, and the senior officers more subdued and in the lounge. But Mess Dinners seem to make their seniors all start the night thinking they are still subalterms together once more, regardless of rank and decades of service. Most can't live up to their own self-promotion and will leave soon after the dining room empties. But some, a mix of the best and the worst, will remain to goad the actual subalterns into drunken risks of life, limb and career.

Playing a subalterns' game of chance, Matt ignores the seating plan until just before going into the dining rom. No sense dwelling on bad news, they agree. As he follows the crowd to the table he glances at the seating plan, discovering that he is seated well up the centre wing of the "E" shaped table. 'Fuck,' he thinks, 'the CO can see me there.' Beside him is some unrecognized Colonel who will likely ignore him all evening, and across the table sits one of the gargoyles, the Major. No-one close by is a familiar face, so he resigns himself to a quiet dinner, pretending polite attentiveness amidst other people's conversations.

Dinner. The courses come and go. Mesclun salad with raspberry vinaigrette. Butternut squash soup. Broiled salmon with dill sauce. Roast beef (invariably overdone), parisienne potatoes, multi-coloured baby carrots. Unimpressed, Matt wonders if he can have a pizza smuggled by the staff. Raspberry cheesecake, drizzled with chocolate. At least the white and red wine glasses are kept more or less filled throughout. Dutifully, in the tradition of young officers everywhere, Matt tries to ensure his glass is empty each time he sees the wine stewards approaching. It's already paid for, he reasons, might as well take advantage.

The table is cleared. Port decanters pass from hand to hand in the usual manner of conflicting traditions. Some hold the decanter above the table, insisting the recipient take it that way. Others deliberately make contact with the crystal and the table top, pushing it to the next officer. The sotto voce arguments over which manner is truly the regimental tradition are old, oft repeated, and never resolved.

The Loyal Toast is called. "Mr Vice, the Queen!" The Vice stands, barely. He is clearly worse for wear, having trusted his dining companions to keep him ready for this solemn duty. Matt notices that the other gargoyle, the Captain, a gleam in his eye—is it mischievousness, or perhaps madness—has been sitting next to the junior subaltern. Matt rolls his eyes. 'Well, there's your problem,' he thinks.

The junior subaltern, Vice-President for the dinner, blurts his required line. "Mesdames at messieurs, la Reine du Canada!"

Glasses are raised. "The Queen!" Port is sipped, with the usual muttered accompaniment by the old guard. "God Bless Her." The scraping of chairs as everyone sits. The process repeats itself, with a different proposer, to toast the Regiment as the Vice slides out of his chair, the night's first casualty.

"Do ye not drink lad?"

Matt blinks. It's the major across the table.

"Pardon me sir?"

"Do ye not drink, lad, you're only takin' wee sips o' that port. Your father would have held the decanter and slugged a full glass for every toast."

'Fuck,' thinks Matt as he mentally frames a reply, 'can't I once attend a Mess Dinner without someone invoking the drunken memory of the old man.'

'Ah, fuck it, if you can't beat 'em …'

Dispensing with a reply, Matt winks at the old major, and downs his glass. Resigning himself to his fate, he reaches for the decanter.

Posted by regimentalrogue

at 12:01 AM EST

Updated: Saturday, 20 December 2014 1:32 AM EST

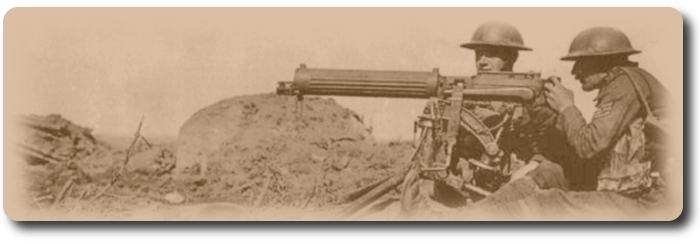

Early in 1915, near Festubert, the Germans threw up a road block supported by a network of trenches which very much annoyed the Canadians opposite. These happened to be the Seventh Battalion, under a young major by the name of Victor Odlum. He worked out a plan to put an end to the nuisance, got it approved and carried it out with brilliant success.

Early in 1915, near Festubert, the Germans threw up a road block supported by a network of trenches which very much annoyed the Canadians opposite. These happened to be the Seventh Battalion, under a young major by the name of Victor Odlum. He worked out a plan to put an end to the nuisance, got it approved and carried it out with brilliant success.

The militia's new role, as outlined by

The militia's new role, as outlined by

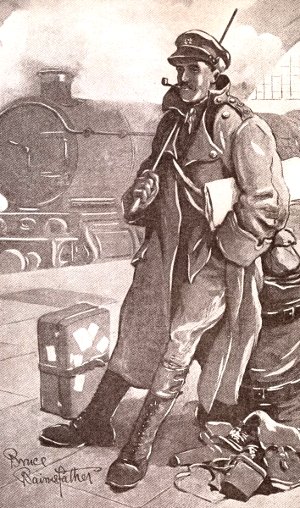

On December 27 [1918], just as the regiment was going forward into Germany, the Squadron Leader said to me, 'Your leave has just come through.'

On December 27 [1918], just as the regiment was going forward into Germany, the Squadron Leader said to me, 'Your leave has just come through.'

London, Oct. 21.—

London, Oct. 21.— Called Black Devils

Called Black Devils