Digging a Trench Under Fire

Topic: CEF

Digging a Trench Under Fire is Regular Task for Tommy Atkins

The Spokesman-Review, Spokane, Washington, 20 March 1916

(Augustus Muir in the London Daily Mail.)

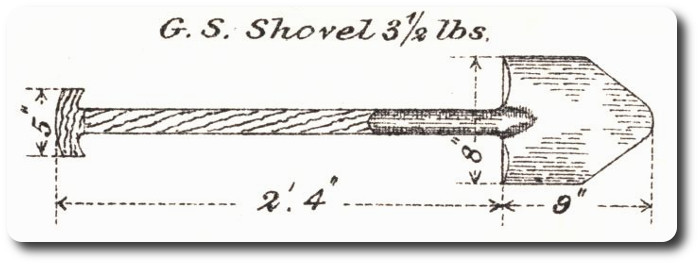

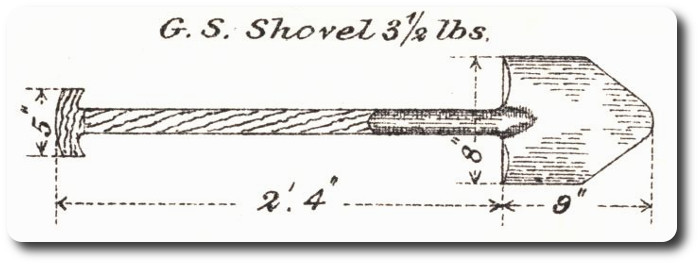

It is with the first clink of pick and shovel that the real danger begins. As soon as the Boches realize that out in front something is doing they get busy, and 10 rounds rapid become too frequent for health. Digging—feverish digging—is the order of the night.

It was the brigade major who began it. I remember the morning distinctly. He came round one the traverse with a periscope in his hand, a staff captain at his heels, and made an exhaustive survey of the ground in front.

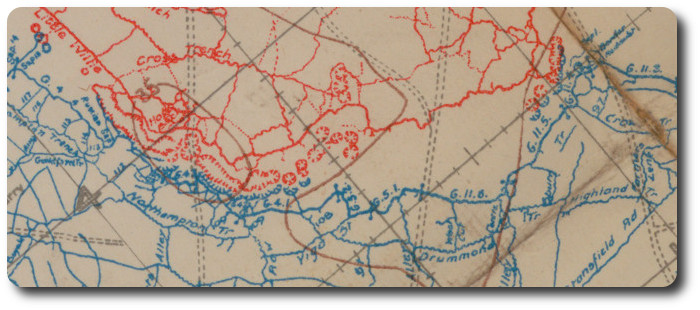

"Bad field of fire," he muttered, "The Boches must be 400 yards away just here; but there's ground in front we can't see—dead ground. Bad field of fire altogether."

"Rotten," agreed the staff captain, "The hollow could hide a couple of companies of the Boches in case of an attack. Now if we put an advance trench out there——"

"Just what I was going to say," said the brigade major. "Just what I've brought you here to see. We'll mention it to the brigadier this afternoon."

In the afternoon the brigadier came down the trench.

"Ex–actly," said the brigadier, in his neat, precise accents, "Ex–actly." He turned to the C.O. of our battalion. "What do you think of it, colonel?"

"Quite agree," said the colonel.

Few Words Set Machinery Going

And that was all that was said; thus ran a few short sentences set a vast machinery at work: The little neat brigadier's "Ex–actly!" was like pressing the button which controlled an immense restrained activity.

Satisfied, the group of officers moved down the trench, leaving behind them the disturbing knowledge that something was about to happen.

That evening we got our orders, and by the morning Tommy knew what the making of an advance trench meant.

A "covering party" is picked. They are put under command of an outstanding N.C.O.—a man who has been tried in the fire of achievement and has been found reliant. Their duties are hazardous and vital. On them devolves the strain of providing a protective screen between the Boches and our working party, which is about to go out. They must lie in the open, watching, waiting, alert, untiring, should they chance to run into a little patrol their work must be short, sharp and to the point. There can be no dallying when it's one's own skin—or that of Fritz. And they must use the bayonet only; for to fire would be but to disclose their locality to a dozen enemy machine guns waiting to belch forth lead.

Ticklish Job of the Patrol

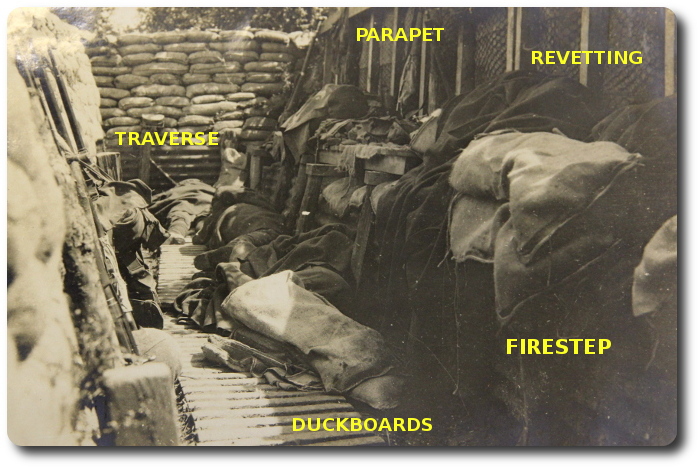

When the hour appointed draw near, these picked men get ready. They stand waiting, cigarette in mouth, for their orders to move. There are the crisp thudding of a maxim down the line, and occasional quick crackle of rifle fire, and the angry roar of bursting shrapnel in the distance. "Patrol ready, Corporal?" The corporal signifies assent; cigarettes are pout out; bayonets are fixed; equipments buckled, and with a last "Cheer-ho!" the covering party clamber over the parapet of the trench and are gone.

Ten or fifteen minutes later a dark figure crawls back, appears for a swift moment against the night sky, and drops with a spatter of mud in the trench. It is the officer. He reports to the company captain that he has "placed" the patrol; that all is ready for the working party. The external order to "Carry on" is given. The next moment a long string of men scramble from the cloggy depths of the trench and follow their officer into the land of unexplored mysteries; the Dead Country; that grey desolation, fraught with unimagined horrors, where the dead are lying; that Long Road which runs from the splashing sea near Dunkirk on the east—for all the world like a vast, grim, black ribbon flung carelessly across Europe.

Function of the Sandbags

Every man bears a sandbag' they are the essence of the whole business. Without them the earlier stages in the making of an advance trench could no more be accomplished than could the completion. The company captain confers with a subaltern; crouching in the open, he gives whispered counsel. "Start here with the trench and make for the outline of that tree; I'll get Kennedy to work toward you with his platoon. You can touch in with each other."

"Right," says the subaltern as his company captain glides out of earshot. "Now then, first man, hand me your sandbag." The subaltern selects his spot and places the sandbag on it. "Hand your bags along the line—pass back the order," Ad so the sandbags travel along the human chain, which stretches back to the firing line and beyond it to a clay pit, where a pack of perspiring Tommies are groveling in the earth and filling the little squat squares of stitched canvas as if their lives depended on their energy. But neither the sweating fellows who fill them nor the subaltern, who lays therm amid the zipping bullets have time to ponder the unique romance residing in these little greyt sandbags, fashioned perchance by some woman's hands in the tranquil firelight of a quiet hearth. Some day—iuf the war spares him—some poet will sing the deathless lyric of sandbags and other mundane things of trench life, but the time is not yet.

Moving toward his left, the subaltern plots out the future trench with its traverses and cover. He needs the eye of a cat for the job, because where the ground is unsuitable the trench must avoid it, and swerve backwards or forward. Half-an-hour's work and his colleague heaves in sight. "I'll touch in with you now," says the subaltern; they place the last few sandbags, and the long line, laid unerringly in the darkness, meets ion the center. The advance trench is happed out.

When the Real Danger Begins

It is with the first clink of pick and shovel that the real danger begins. As soon as the Boches realize that out in front something is doing they get busy, and 10 rounds rapid become too frequent for health. Digging—feverish digging—is the order of the night. Your arms are aching, you head is splitting, you want to lie down and rest forever; but, urged by the knowledge that they must occupy the trench in three days, the men settle down to it with braced sinews. A flare goes up in the night, making a lurid green scar in the sky and falling 20 yards away. Picks and shovels are dropped and Platoon Fifteen lies hugging the wet earth, barely daring to twitch an eyelid. As soon as the flare burns out they are at it again like clustering bees. With "Stand to!" an hour before dawn comes the order to retire. The men file back, thanking their stars that they even have a trench to come home to—after all there is no place like home. Picks and shovels are stored. The officer creeps out and recalls the patrol.

Death Takes Its Toll

Dawn comes, and with it repose and respite, till night relentlessly drags them forth again to face the machine guns that have been paid during the day on the fresh sandbags. Casualties? These are but little incidents in the great adventure. Two nights pass and often a quick cry has told someone's mates that he is passing from them! Casualties? The subaltern puts a black stroke against each man in his platoon roll, but would fain hold back his hand from adding up the number.

As dawn breaks on the third day the subaltern inspects his work. The advance trench is finished; there are a firing-step, loopholes, cover and a communications trench has been cut out. But will it do? Will the brigadier be satisfied? In the forenoon the brigadier himself comes 'round. "An excellent field of fire," he says. "How many men have you lost?"

Such is the epic of the advance trench.

Posted by regimentalrogue

at 12:01 AM EDT

Here is a favourite recipe: Cut fine a half a pound of cheese, mix with a tin of canned beef, add bread crumbs and all the bacon grease available. Fry over a candle in a mess-tin and eat quickly, because, if the odour spreads, a crowd will gather, and you will either be lynched or forced to divide, according to the humour of the spectators.

Here is a favourite recipe: Cut fine a half a pound of cheese, mix with a tin of canned beef, add bread crumbs and all the bacon grease available. Fry over a candle in a mess-tin and eat quickly, because, if the odour spreads, a crowd will gather, and you will either be lynched or forced to divide, according to the humour of the spectators.

Harold Jukes Marshall, assayer of B.N.A. of this city, has received the following interesting letter from his brother,

Harold Jukes Marshall, assayer of B.N.A. of this city, has received the following interesting letter from his brother,