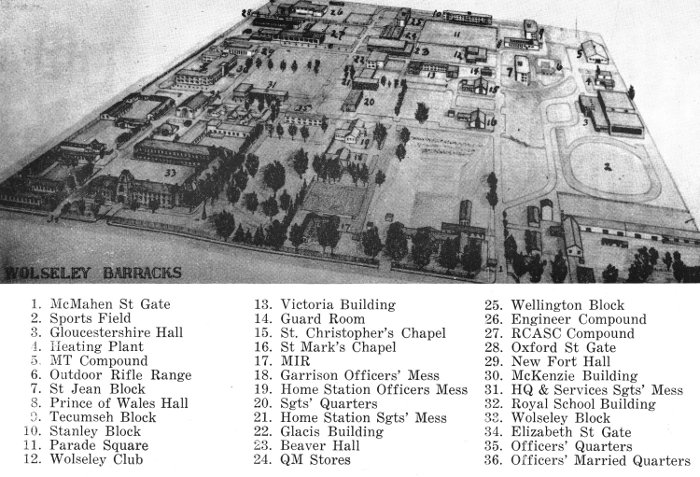

Brief History of Wolseley Barracks

Topic: Wolseley Barracks

A Brief History of Wolseley Barracks

Canadian Forces Base London

(Undated document, last date in document is 1963. All details are as presented in original and may require confirmation from additional sources.)

1840. — Groups were stationed in what is now Victoria Park. They were quartered in a log barracks named "TECUMSEH" after the famous Indian Chief.

1873. — Tecumseh Log Barracks burned to the ground.

1886. —

(1) The City of London traded the present site of Wolseley Barracks and small surrounding area for the Ordnance property in Victoria Park. The area at Oxford and Adelaide Streets was then outside the city limits in the area known as Carling Heights, RCE records indicate that $1.00 was charged in consideration for the exchange of Victoria Park and Carling Heights properties in which 55 acres of land were involved.

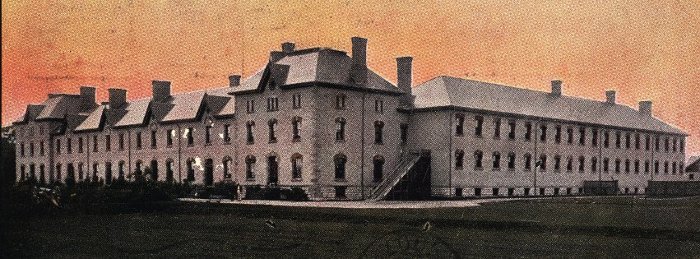

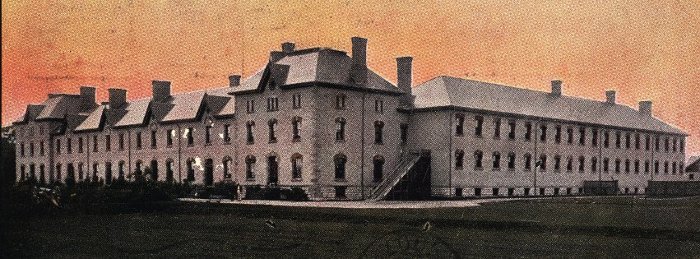

(2) Construction of "A" Block, which as known as the Infantry School Building started, along with the following buildings:

(a) Stables, which have now been torn down.

(b) Picquet Hut for guarding the stable and RCE, RCASC Compound and the Infantry School Building which has since been torn down.

(c) Building "T", which may originally have been built as an RCOC Depot.

(d) Two million bricks were used in the construction of "A" Block. The bricks were made in close proximity to the barracks site. RCE records indicate that the cost of the Infantry Scbool Building was $77,300.

1888. —

(1) The buildings, begun in l886, were completed and the new barracks was then termed "Infantry School London, Ontario" (extracted from old General Orders). The first troops to occuppy the barracks were "D" Company, Infantry School Corps, commanded by Lt.-Col. Henry Smith.

(2) Service units in the barrack area included Engineers, Service Corps, and Ordnance. Married quarters were provided in the Block.

1889. — An additional 26 acres were purchased from the City of London by the Militia and Defence Ministry. Total cost was $25,000

1894. — The Barracks was renamed "Wolseley Barracks" in honour of Viscount Wolseley.

1914-18. — Litttle change took place in the barracks until the First World War. Some buildings of a semi-temporary nature were constructed, but the majority of the troops were under canvas in the area of Gloucestershire Hall, known as "The Flats." Another building named Tecumseh Barracks was built in this area during the period.

1923. — HQ and "C" Company, RCR, occupted Tecumseh Barracks from 7 Dec 1920 to Apr 1923. This barracks burned down.

1930. — Building "U", near the McMahen St. Gate, was built.

1936. — The Royal School Building was completed at a cost of $36,000.

1938. — The last horses used by RCASC were retired and mechanical transport appeared in Wolseley Barracks.

NOTE: The riding ring for exercising the horses ridden by the Area Commander, the CO and the Adjutant of The RCR, was in the area where the present Victoria building is located.

1939-45. — Many buildings of wartime construction ("H" Huts) sprang up and were used after the war by both tthe Regulars and Militia. They were gradually torn down to make room for new buildings, or as no longer required, until in November 1963 only three or four remained.

1952-57. — The completion of a six million dollar expansion project, which changed the face of the barracks to its present shape. RCE records show a cost of $6,918,974.

(Image from The regimental journal of The RCR.)

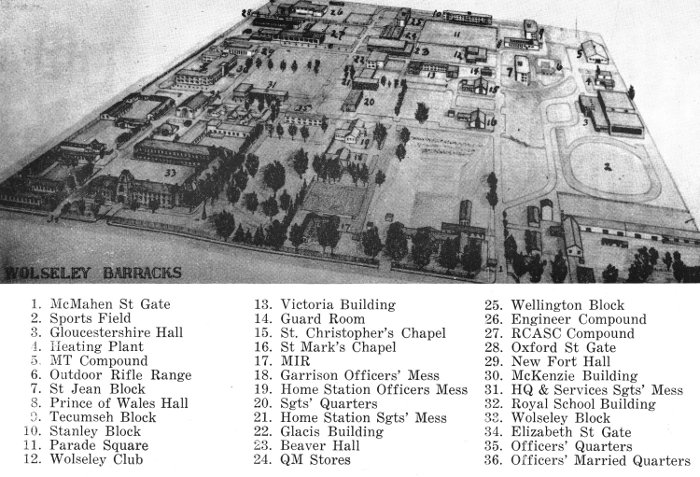

Origin of the named used for buildings was from associations of The RCR, rather than from Royalty or Governors-General:

(1) No. 1 Barrack Block — MacKenzie Building. From Thomas MacKenzie, the first man to enlist in the RCR, 7 Jan 84.

(2) No. 2 Barrack Block — Wellington Block. Taken from Wellington Barracks, Halifax, which The RCR occupied from 1904 to 1940.

(3) No. 3 Barrack Block — Stanley Block. Taken from Stanley Barracks, Toronto, which The RCR occupied from 1899 to 1940.

(4) No. 4 Barrack Block — Tecumseh Block. After the Old Tecumseh Barracks, London, which The RCR occupied from 1920 to 1923.

(5) No. 5 Barrack Block — St. Jean Block. Taken from the original location of "B" Company, The Infantry Corps School, in 1884 at St. Jean, PQ.

(6) Lecture Training Building — Glacis Building. Taken from Glacis Barracks, Halifax, which the RCR occupied from 1900 to 1904.

(7) Gymnasium — Gloucestershire Hall. From the RCR allied regiment of the British Army.

(8) Adminsitration Building — Victoria Building. From Victoria Barracks, Petawawa; RCR from 1948 to 1954.

(9) No. 1 Mess Hall — New Fort Hall. Taken from New Fort Barracks, Toronto, The RCR Barracks from 1884 to 1898.

(10) No. 2 Mess Hall — Prince of Wales. Taken from the Prince of Wales Barracks, Montreal, The RCR Barracks from 1920 to 1924.

Posted by regimentalrogue

at 12:01 AM EDT

Updated: Sunday, 19 January 2020 2:55 PM EST

1. Lack of Appreciation for the Problem.

1. Lack of Appreciation for the Problem.

a. The use of information provided by PWs and

a. The use of information provided by PWs and

Well, I've got back to camp again. We have had a rough twenty-four hours of it; it rained nearly the whole time. The enemy kept pitching shell into us nearly all night, and it took us all our time to dodge their Whistling Dicks (huge shell), as our men have named them. We were standing nearly up to our knees in mud and water, like a lot of drowned rats, nearly all night; the cold, bleak wind cutting through our thin clothing (that now is getting very thin and full of holes, and nothing to mend it with). This is ten times worse than all the fighting.

Well, I've got back to camp again. We have had a rough twenty-four hours of it; it rained nearly the whole time. The enemy kept pitching shell into us nearly all night, and it took us all our time to dodge their Whistling Dicks (huge shell), as our men have named them. We were standing nearly up to our knees in mud and water, like a lot of drowned rats, nearly all night; the cold, bleak wind cutting through our thin clothing (that now is getting very thin and full of holes, and nothing to mend it with). This is ten times worse than all the fighting.

He is a patriot, is highly motivated and has integrity.

He is a patriot, is highly motivated and has integrity.