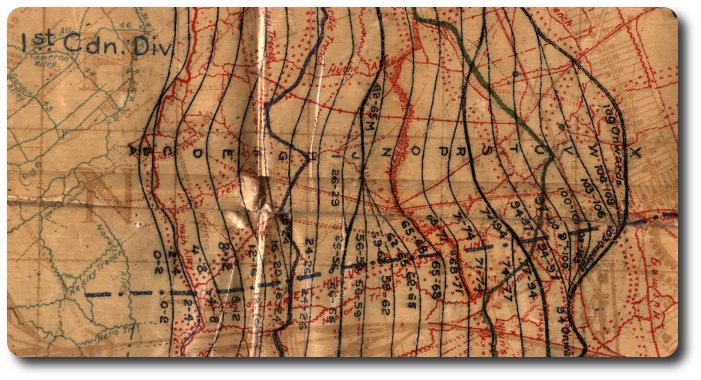

The Creeping Barrage (1918)

Topic: CEF

The Creeping Barrage (1918)

S.S. 135 — The Division in Attack; Issued by the General Staff, November, 1918

Appendix A – Artillery in Attack

Barrages

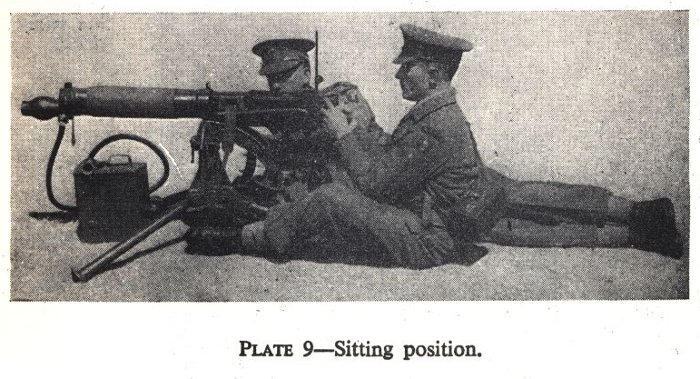

(i.) Object.—The object of the barrage is to prevent the enemy from manning his defence and installing machine guns in time to arrest the advance of the assaulting infantry. The barrage must be sufficiently heavy, therefore, to keep the enemy in his dug-outs, and sufficiently accurate to allow the infantry to get so close to the points to be attacks that it can cross the remaining distance before the enemy is able to man his defences. The barrage should be organized in depth to ensure, as far as possible, the protection of the infantry from effective rifle and machine gun fire. What the depth of each actual barrage may be, depends primarily on the artillery resources available, the configuration of the ground and the enemy's dispositions for the defence. The enemy's machine gun fire may prove dangerous at ranges up to 2,500 yards from the attacking infantry.

(ii.) Organization.—In accordance with the foregoing principles, the barrage is organized in several belts of fire, the belt nearest to the advancing infantry being composed of the fire of the major portion of the 18-pdr. guns and generally known as the "creeping barrage."

The 4.5" howitzers and the remainder of the 18-pdrs. form a barrage in advance of the "creeping barrage"; their fire, while dwelling on strong points, and working up communication trenches, is at the same time organize in depth.

Beyond this again, a further belt of fire is formed by medium and heavy howitzers and a proportion of the 60-pdrs. their fire is directed so as to search all ground which commands the line of advance of the infantry or from which it is possible that indirect machine gun fire might be brought to bear through the creeping barrage. Especial attention must be paid to localities from which flanking fire can be brought to bear on the front of attack.

All these barrages roll hack according to a time table, the main principle being that there should always be a searching fire up to 2,000-2,500 yards in front of the advancing infantry. The fire, other than that of the "creeping barrage" should not follow as even cadence, or lift in regular lines. It should be so handled that the enemy's machine gunners may be unable to realize when the lift has taken place.

Finally, from the beginning of the barrage, the fire of long-range guns of all natures should be, used against the probable approaches of troops which may be brought up for the purpose of counter attack.

(iii.) The Creeping Barrage.—In the first assault, the "creeping barrage" opens and dwells a few minutes on the enemy's foremost position. If the opposing 1ines are so close that this cannot be done without endangering the attacking troops, or if the position of our own front line is uncertain, it is advisable to withdraw the troops slightly before they form up for the assault in order that there may be no danger of opening fire beyond any locality which the enemy may occupy with advanced machine guns.

In an attack on an entrenched system the barrage does not as a rule lift direct from one trench to another, but creeps slowly forward, sweeping all the intervening ground in order to deal with any machine guns or riflemen pushed out into shell-holes in front or, of behind, the trenches. This creeping barrage will dwell for a certain time on each definite trench line to be assaulted.

From both an artillery and an infantry point of view simplicity in the organization of the barrage is desirable; curves and irregularities must be avoided as far as possible. The advance of the infantry will be much facilitated if the creeping barrage is moved forward in a straight line parallel to the line of departure of the assault.

The barrage should be arranged so as to help any change of direction which the troops may have to make. Direction is a matter of particular importance. Troops are trained to keep up to the barrage and can only do so by conforming to its shape. Curves and irregularities in the barrage are, therefore, always apt to cause a loss of direction.

(iv.) Pace of the creeping barrage.—(a) The pace of the barrage is governed by the pace decided on for the infantry advance. The pace decided on for the infantry advance is dependent on local conditions, and it is impossible, therefore, to lay down as a general rule any definite rate of movement for the barrage, the pace of which will, with rare exceptions, be identical with that decided on Eor the infantry.

In estimating the correct rate of advance, the following factors should be carefully weighed:—

First—the probable resistance of the enemy, depending on the moral, quality and number of his troops, the nature of his dispositions and the strength of his defences.

Secondly—The state of ground and weather. The extent to which the ground has been cut up by shell fire, the presence or absence of mud, wet or dry weather conditions, and the existence of woods, houses, villages and streams in the line of advance, all affect the pace at which the infantry can move.

Over good ground, and in the absence of serious opposition, infantry can advance at a rate varying, according to the depth of the advance, between 50 and 100 yards a minute.

Thirdly—The length of the advance. A uniform pace for the barrage throughout the advance is, as a rule, unsound; the general principle should be for it to move more quickly at the start and to reduce its pace during the later stages, in order to allow the infantry time to reorganize.

In the case of a long advance, the attacking troops should be afforded the opportunity of recovering their places close up to the barrage by means of short pauses between the different objectives; the barrage should also be kept on each objective for an increased period in order to ensure that the attacking troops are closed up and ready to rush to the assault immediately the lift takes place.

Fourthly—The moral effect on the attacking troops. A slow advance checks, a rapid advance stimulates the keenness of the attacking troops.

(b) If the pace decided on is too rapid, the whole advantage of the barrage will be lost, since the attacking infantry will fail to keep up with it and the enemy will be given time to man his fefences before he is attacked.

As a result, the advance may be brought to a standstill in close range pf the enemy's rifle and machine gun fire, while the barrage will continue to move on in accordance with the time table.

If, on the other hand, the pace decided on is too slow, the rear portions of the attacking force will tend to push on too fast and will become mingled with the leading portions, thereby forming a denser line and incurring heavier casualties, and also losing the momentum of the attack. Further, the enemy will be given time in which to withdraw his guns and infantry, and to reorganize his defence.

Finally, it must be remembered that the slower the rate of advance the greater will be the amount of ammunition expended in the barrage. This is an important factor for consideration in cases where the rapidity of the general advance may have rendered ammunition supply a matter of difficulty.

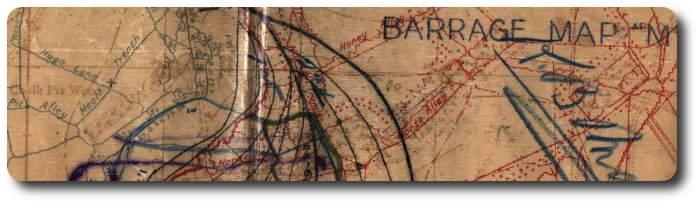

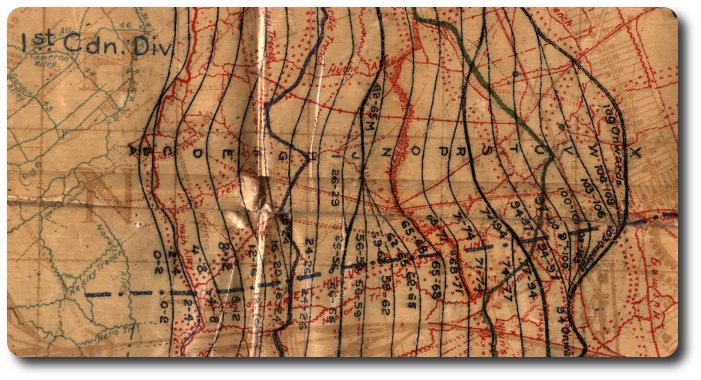

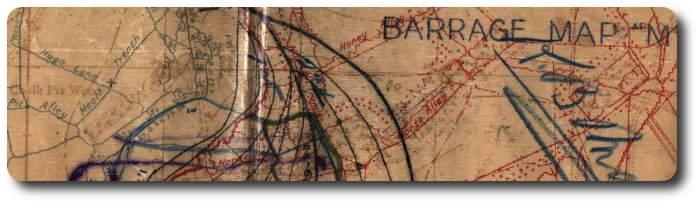

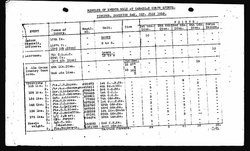

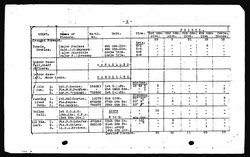

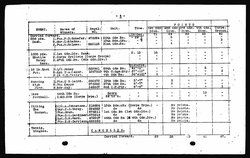

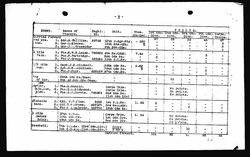

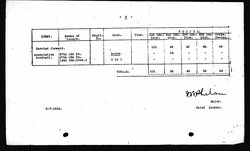

(v.) Barrage Tables (or maps).—The arrangements for the barrages are made, as part of the corps artillery plan, by the corps commander after consultation with the divisional commanders, particular attention being paid to the points of junction between divisions to ensure that the barrages on each divisional front overlap properly.

Lifts and timings worked out are then embodied in a time table or map and issued to all concerned, the corps being responsible that these maps or tables are issued in sufficient time to enable the artillery to carry out the necessary arrangements. [From a later paragraph these arrangements include the supply of additional ammunition to batteries, the working out of firing data for the guns, and the setting of fuses and preparation of ammunition according ti the firing plan]

When the barrage maps or tables have been approved and issued by the Corps, no alterations by subordinate commanders are allowed, unless there is a change in the general plan of attack.

Posted by regimentalrogue

at 12:01 AM EDT

Updated: Tuesday, 9 September 2014 7:43 AM EDT

But the little armistice that fewer than a thousand Canadians and Germans saw was staged by only one man.

But the little armistice that fewer than a thousand Canadians and Germans saw was staged by only one man.

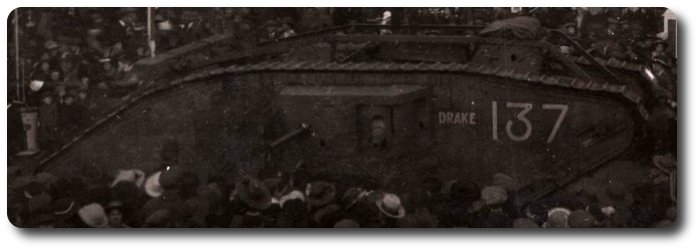

When the War commenced Germany was popularly supposed to lead the world in scientific implements of warfare; as a matter of fact she lead chiefly in preparedness and quantity. As the struggle developed initiative passed to the British Allies whose aeroplanes knocked out the

When the War commenced Germany was popularly supposed to lead the world in scientific implements of warfare; as a matter of fact she lead chiefly in preparedness and quantity. As the struggle developed initiative passed to the British Allies whose aeroplanes knocked out the  In Naval types and designs the British were dominant—even the

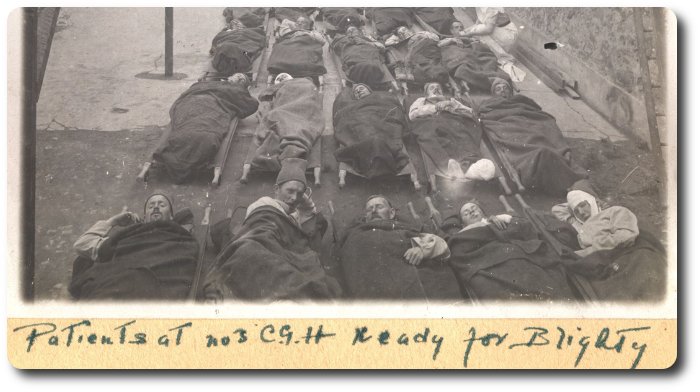

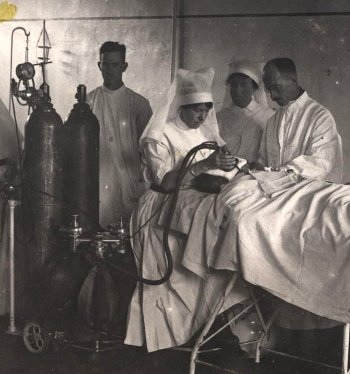

In Naval types and designs the British were dominant—even the  Surgical and medical developments were one of the miracles of War. That, with the single exception of the

Surgical and medical developments were one of the miracles of War. That, with the single exception of the

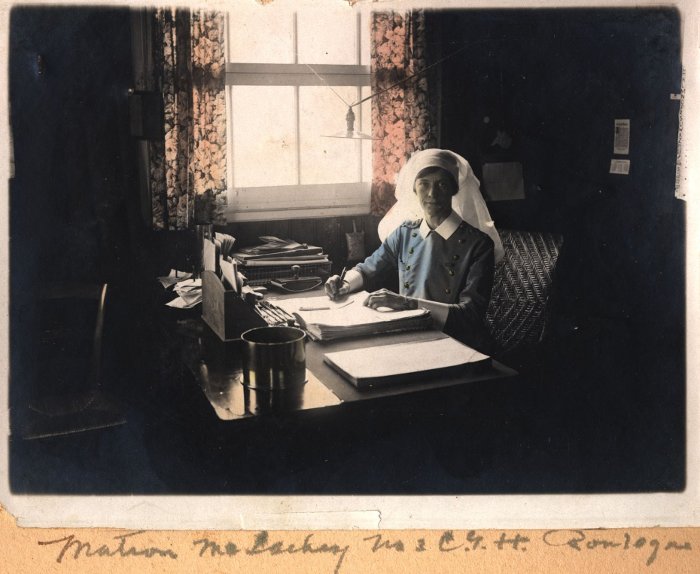

Katherine Osborne MacLatchy was born at

Katherine Osborne MacLatchy was born at

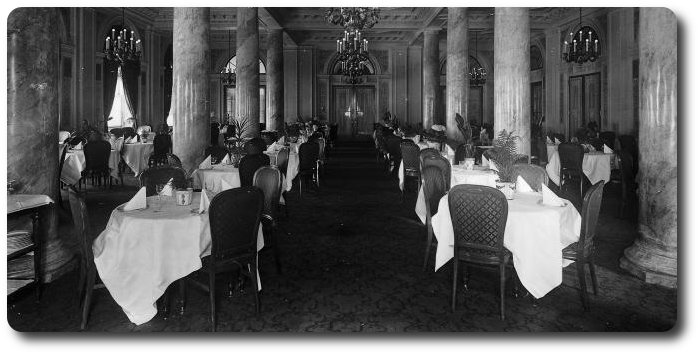

Many decorated heroes foregathered last evening at a dinner given at the

Many decorated heroes foregathered last evening at a dinner given at the

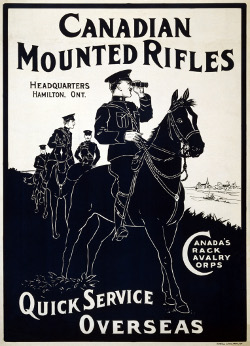

A warm reception was given Lieut.-Col. Rhoades when he rose to speak of the history of the Mounted Rifles and the splendid work they had done overseas. He remarked that the C.M.R. Had always worked together at the front as a happy family, officers and men always being willing to take their share of the hard work and hard knocks.

A warm reception was given Lieut.-Col. Rhoades when he rose to speak of the history of the Mounted Rifles and the splendid work they had done overseas. He remarked that the C.M.R. Had always worked together at the front as a happy family, officers and men always being willing to take their share of the hard work and hard knocks.

Down the street from Parliament Hill, at the centre of

Down the street from Parliament Hill, at the centre of