Canadian Soldier Recounts Armistice Day Experiences

Topic: CEF

Canadian Soldier Recounts Armistice Day Experiences

War Time Happenings Told by Ex-Infantryman—Tree Saved Two Lives

Schenectady Gazette, Friday Morning, 3 November 1922

The armistice was signed November 11, 1918, Schenectady's observance of the day this year will be the most imposing so far carried out, with a mammoth parade including thousands of marchers. Local veterans are recounting their experiences on the last day of the war; two soldiers of the Unites States forces have recounted their experiences, and now an ex-soldier of the Canadian infantry recounts his. His letter follows:

The armistice was signed November 11, 1918, Schenectady's observance of the day this year will be the most imposing so far carried out, with a mammoth parade including thousands of marchers. Local veterans are recounting their experiences on the last day of the war; two soldiers of the Unites States forces have recounted their experiences, and now an ex-soldier of the Canadian infantry recounts his. His letter follows:

"On November 7 we were in support of the battalions which we relieved and were under constant shell fire. The\rough those dozens of miles and the many more which followed we lived practically on vegetables from native gardens, as we were going too fast for the transport to keep in touch with us. In all those miles I saw but one goat to represent animal life. All the farmers' stock had been commandeered by the enemy; was not able to learn how the one goat escaped.

"It was some time in the middle of the night when we relieved the C.M.R. battalion outside Thulin, and we did not waste many minutes organizing our plans for advance. I was in charge of the signallers of number one company and so attached to company headquarters. Our company started in the lead and soon we were entering Thulin, receiving a hearty welcome from the enemy snipers and machine gunners who were left behind for rear guard action, as the main body of troops evacuated when they decided we intended to enter the town.

"the retreat at this time was so quickly forces and carried out that civilians were not evacuated, as had been the rule. Once established in Thulin we entered a house where we found the occupants still crouching in the cellar.

"Imagine their outbursts of joy when they found their friends instead of another invasion of the enemy! Shouts of 'Vive les Canadians' were heard from every corner. After a great deal of heavy marching and long hours I must admit that I was somewhat tired and glad of a chance to sit down for a minute. Revived by a little drink of 'madame's vin rouge' I felt that I could enjoy a smoke, since I had not had one for several hours.

"No sooner had I lighted the match than madame and all others shouted in one voice, 'Caspoot!' At any rate that is how it sounded to me and which afterwards I learned to mean 'kill.' We had been used to the word 'fini,' but in this occupied territory they had learned to express themselves in German war phrases. Suffice it to say that I had my smoke in peace and was soon able to convince the family that they were not in any immediate danger. Such contentment and ease was too good to last, and in less than an hour we were on our way again with dawn fast approaching.

"During the day of the eighth it was cloudy and unsettled; somewhat chilly and depressive weather, but our morale was so high that weather conditions could not affect our gaiety. A few advanced guards, a little scouting mixed with an occasional flash of the lamp or a wag of a flag and preparations were ready for our attack on Henain, short but decisive, and the enemy was on his way, leaving the town in our care. Here we were greeted again by a population so overjoyed that they forgot all personal fears and marched by the hundreds down the streets with us, only hesitating occasionally when we were greeted by a sudden burst from a machine gun hidden in some mine shaft. An occasional bark of a field gun, a sudden crash, and another house was in flames and ruin but still the people were happy, ever eager to advise us of an enemy outpost in some old house, mine shaft or cluster of bushes, forgetting their danger in leading us to a place of vantage, where we could exercise our skill.

"Soon the way was forced open and we were now marching on to Boussi the next town, several kilometres distant. By such persistent advancing we were beginning to appreciate the fact that our battalion was slowly becoming weakened, as our casualties were quite numerous and no reinforcements. Tired and war worn with depleted ranks we moved forward along a railroad until heavy fire forced us to use open order skirmishing practice in the fields there to advance in short rushes and take cover as best as we could behind hay stacks, trees or whatever object was available.

"Poor Fritz! He hated to give up Boussu. There he had a hospital and many of our prisoners. Sharp and stubborn engagements took place with his rear guards to give them a chance to take their sick and wounded from the hospital. But again as always before when we had decided upon an objective it was soon in our keeping. In Boussu we entertained several of our allied prisoners who had escaped and got through enemy lines because now they didn't exercise much care in guarding them. Every prisoner that escaped meant one less to feed, and every ounce of food counted in those days. Finally establishing our right to Boussu about midnight, we remained there until morning. We had been on constant watch, move and offensive for about 30 hours without stopping to rest or eat, and in that time had covered a distance of many miles, relieved many thousand civilians and encountered several sharp engagements with the enemy.

"A few hours' rest, a feed and a few winks of sleep and Saturday, the ninth, began to dawn. Somewhat refreshed and a song of victory in our hearts once more we buckled on our armor; once more the incessant tramp, tramp, tramp as we followed closely upon the enemy, wondering and watching for our next encounter. Had he fled entirely? No shrieking of shells or twang of bullets pierced the air. A beautiful, fine morning dawned, and save for the distant roar of the guns on our flanks, the world seemed at peace. Too good to last, and soon we were awakened to realization of war once more. We were now close upon Hornu, which soon fell into our hands with scarcely a struggle, and so on to Ouaregnon with little resistance.

"A few hours' rest, a feed and a few winks of sleep and Saturday, the ninth, began to dawn. Somewhat refreshed and a song of victory in our hearts once more we buckled on our armor; once more the incessant tramp, tramp, tramp as we followed closely upon the enemy, wondering and watching for our next encounter. Had he fled entirely? No shrieking of shells or twang of bullets pierced the air. A beautiful, fine morning dawned, and save for the distant roar of the guns on our flanks, the world seemed at peace. Too good to last, and soon we were awakened to realization of war once more. We were now close upon Hornu, which soon fell into our hands with scarcely a struggle, and so on to Ouaregnon with little resistance.

"Had the enemy seen the wisdom of retreating without trying to resist us? Not so. He had another object in view which he put into practice. He retired on through the next town Jemappes, with very little resistance and again we were met with maddening cheers from an overjoyed population at their freedom.

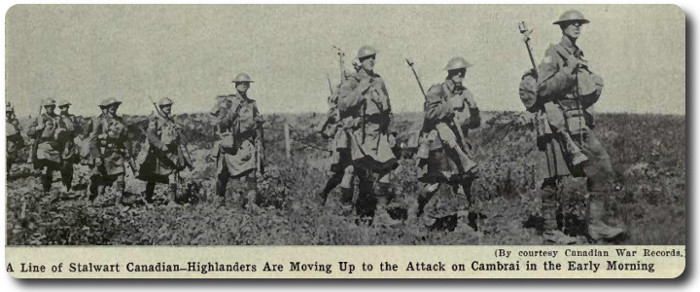

"Another three of four miles and we would be in the city of Mons, the city where first the British 'first 80,000' met the enemy a few days after the outbreak of the war, August, 1914. Here at Mons the enemy would resist an advance with vigor as they were resisted in '14. A sudden rustling noise broke through the roar of the guns and rifle fire which was being poured in upon us as soon as we got beyond Jencappes, and soon one of our eight field pieces of artillery drawn by galloping horses came rushing by us. Shouts of 'Good old third division' were heard ion every side as the gun and crew rushed by under the charge of their captain mounted on his war tired horse. This was the first piece of artillery to break through ahead of the infantry, but we gave them shouts of welcome.

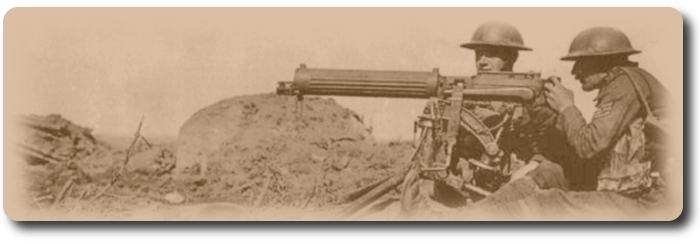

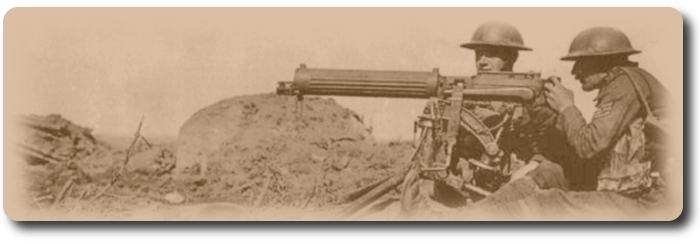

"Halt! Action Front!" we heard the command and saw the gun swing into action a few yards ahead. What a difference from those early days of the war as we sat in mud with our artillery in the rear, sunk in the mud up to the hubs of the gun carriages, never moving for weeks. A puff of smoke, a sudden roar, and one machine gun post which had been causing us considerable alarm and annoyance ceased its rat-tat-tat. Now we are in the lead again, but soon the gun is rushed by us and again the unfamiliar order. Another post has ceased to exist, and so on up to the village of Cuenne, which is a suburb of Mons.

"There are two direct and main routes leading into Mons through Cuesmes—one to the left which crosses the railroad and canal, which we took, and the other to the right which number two company took, while three and four followed behind number two company. Needless to say that we were doubly welcomed in Cuesmes, and the inhabitants showed it by marching along with us, making out from estaminets with bottles of wine and light beer to show their gratitude and quicken our step, which was becoming fatigued from lack of sleep, rest and proper nourishment. Slowly advancing around a turn in the street we were halted by a sudden furious outburst from several machine guns close by.

"In all my 39 months of active service I laughed more at this particular instant than any time before. Even more, I believe, than when I saw some good musical comedy in the Follies Bergere in Paris. We were going up this wide street, which was lined with large trees in each side. As I stated before, during these engagements I was with the signal section. Now I'll give you some idea of the load I was carrying. Those days we could not use the telegraph system of visual methods. Each man was equipped with a flag, a disc and one electric lamp (24 pounds weight) to each company. Besides this signalling equipment we carried 170 rounds of ammunition, our rifle and our full marching order pack. The machine gunners had a great deal of .303 S.A.A. to carry for their Lewis guns besides all their other equipment, and some of them were almost exhausted. At that time I was carrying my regular equipment plus the lamp and one container of ammunition for a pal of mine in the gun crew, who was almost exhausted. With all that equipment slung over my shoulder I looked like Santa Claus on Christmas eve, especially since I had not had a shave in three days.

"Along this road was a ditch enclosed with a single strand barbed wire fence. When the machine gun barrage opened everyone disappeared through the barbed wire fence into the ditch, but a little fat French Canadian, another, and myself. He was too stout and clumsy to get through, while I was too heavily loaded. My next resort was to jump behind a large tree while the other fellow sprawled out upon the ground behind me. For once in my life I was thankful for a large tree, because that tree was poured full of lead, while I escaped without injury.

"You wonder what amused me? Well, there I stood doing my best to get untangled from my load so I could dive in the ditch with the others, while all the time talking as if I could be heard and heeded, 'Fritz, for Lord's sake, behave,' and at the same time my pal was shouting for me to get down. On the opposite side of the road stood another chap behind a tree and his mess kit was punctured like a sieve. What appealed to me as so funny was that this other chap, almost invisible reminded me very much like William S. Hart in one of his western pictures, and so the whole situation struck me as humorous. In any event I succeeded in getting into the ditch unharmed and later collected my equipment.

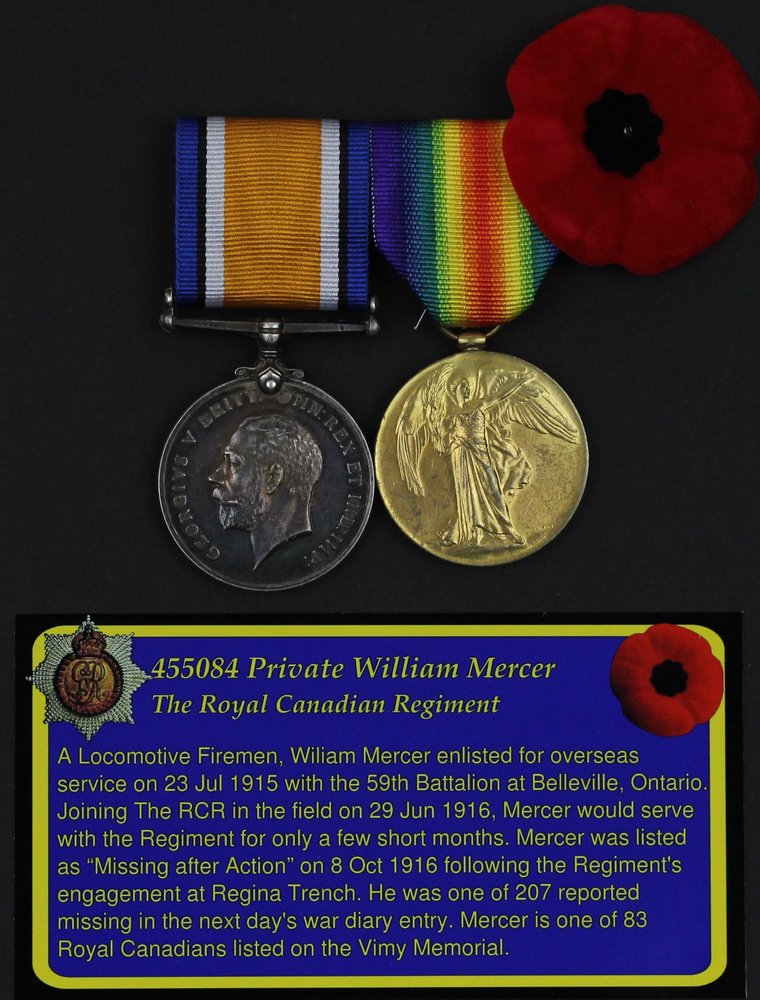

"It was while we were lying there in the ditch making ready top proceed further that we heard the rumor regarding the armistice. A dispatch rider from headquarters came up looking for the company of engineers to whom he had to report and he said they were talking about it at divisional headquarters. The German delegation had crossed our lines, so he told us, and were on their way to Paris. Well, we were quite sure they would accept the allied demands within the 72 hours allowed them, but still we couldn't give up until the time came. Perhaps you can realize to a certain extent how we felt then. Feeling almost certain the armistice would be signed soon and feeling a regular hail storm of machine gun fire and light artillery made things a little unpleasant and uncertain. You know it was 'quite tough' on those chaps who were wounded and killed after that. But we all had to take our chances and do our duty, carrying on 'just the same as if it were two or three years gone by.' Fritz marched through Mons in '14 and we decided to march through it in '18, no matter what he thought about it. We were supposed to be relieved by the R.C.R's before this, but we hadn't got inside the city as yet, so we were satisfied because we wanted to get in first. We did and soon had the enemy looking for safer sections on the opposite side of the city.

"Early Sunday morning the R.C.R's came up and went on into the city and we went back to Jemappes to have something to eat and a good sleep. We had the eats but there was too much excitement to sleep. I can't begin to describe the enthusiasm with which we were met on our return to that town. That night I slept on a bed, the first time I had slept on anything otherwise than the floor or ground since my trip to the hospital in February of that year. Early Monday morning we were met with shouts of joy and welcome. Other troops had arrived and the city was absolutely covered with flags and national colors. Where the people had them hidden in more than I ever learned. The enemy had withdrawn and just a few troops were guarding the entrances. The signal for the signing was to be blue flares dropped from the airplanes flying over the city. How so many planes were given the opportunity of giving the signal I don't know, but hundreds of them hovered over Mons. We were all drawn up in review order in front of the city hall waiting for the signal. At 11 o'clock on the dot as the big clock tolled, blue flares filled the air, as we presented arms to victory. The war was over, but we could not realize it until an hour or so later a German general drove into the city with his car decorated in white and stopped in front of the city hall. His mission I won't describe, but it was military."

Posted by regimentalrogue

at 12:01 AM EST

In this country of all countries, the infantry has been the weapon par excellence. When we think of the British Army we think of the infantryman from the earliest times—the Saxon wall at Hastings, the bowmen at Crecy, the six regiments at Minden, the column at Fontenoy, the "diehards" at Albuera, the squares at Waterloo, the "thin red line" in the Crimea, the Second Corps at Le Cateau, the 15th Division at Loos, the long agony on the Somme and at Passchendaele, and in this war the retreat to Dunkirk, the battles at El Alamein, at Anzio, at Falaise, and on the Rhine.

In this country of all countries, the infantry has been the weapon par excellence. When we think of the British Army we think of the infantryman from the earliest times—the Saxon wall at Hastings, the bowmen at Crecy, the six regiments at Minden, the column at Fontenoy, the "diehards" at Albuera, the squares at Waterloo, the "thin red line" in the Crimea, the Second Corps at Le Cateau, the 15th Division at Loos, the long agony on the Somme and at Passchendaele, and in this war the retreat to Dunkirk, the battles at El Alamein, at Anzio, at Falaise, and on the Rhine.

My camel, the

My camel, the

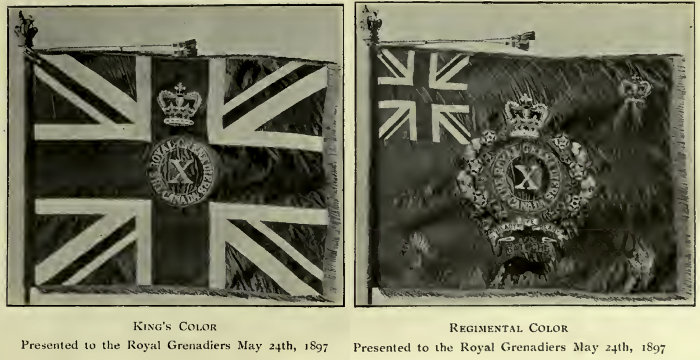

November 13th, 1898, is a date possessing special interest for the Royal Grenadiers, as the one upon which the regiment deposited their old colors with all due honor in St. James' Cathedral. The presence of his Lordship the Bishop of Toronto, the Rector, the Right Rev. Dr. Sullivan, and an array of Canons in their stately robes, the brilliant colors of the uniforms, the impressive formula, all tended to great solemnity; and when the treasured colors, their brilliancy dimmed by the battle and the breeze, were received at the chancel steps by His Lordship, the Bishop, while the organ played "Home, Sweet Home," emotion ran high and the tears were not far from the eyes of the staunchest soldier present. A touching reference by the Rector in his earnest address to the fallen heroes of the Northwest rebellion, drew many an eye to the brass tablet, wreathed in evergreen, and studded with white chrysanthemums, to the memory of Lieut. William Charles Fitch, "killed in action at Batoche," and to the one similarly wreathed, in token of remembrance, to Capt. Andrew Maxwell Irving.

November 13th, 1898, is a date possessing special interest for the Royal Grenadiers, as the one upon which the regiment deposited their old colors with all due honor in St. James' Cathedral. The presence of his Lordship the Bishop of Toronto, the Rector, the Right Rev. Dr. Sullivan, and an array of Canons in their stately robes, the brilliant colors of the uniforms, the impressive formula, all tended to great solemnity; and when the treasured colors, their brilliancy dimmed by the battle and the breeze, were received at the chancel steps by His Lordship, the Bishop, while the organ played "Home, Sweet Home," emotion ran high and the tears were not far from the eyes of the staunchest soldier present. A touching reference by the Rector in his earnest address to the fallen heroes of the Northwest rebellion, drew many an eye to the brass tablet, wreathed in evergreen, and studded with white chrysanthemums, to the memory of Lieut. William Charles Fitch, "killed in action at Batoche," and to the one similarly wreathed, in token of remembrance, to Capt. Andrew Maxwell Irving.

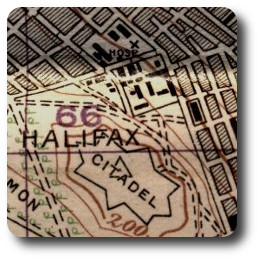

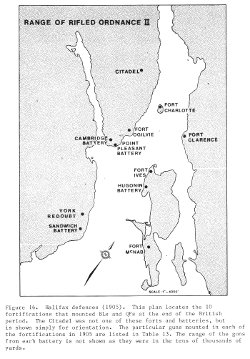

The Brunswick and Cogwell Streets area of Halifax, as shown on an 1894 map of the city.

The Brunswick and Cogwell Streets area of Halifax, as shown on an 1894 map of the city.

Michael Kelly, a private in the

Michael Kelly, a private in the

Both regiments fought at

Both regiments fought at

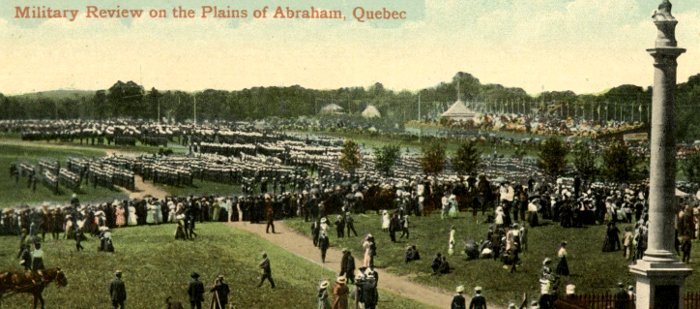

It was only natural that there should be outstanding features, but this was through no lack of perfection with which the different items were performed by respective units, but rather the nature of the display. Gentlemen Cadets of the

It was only natural that there should be outstanding features, but this was through no lack of perfection with which the different items were performed by respective units, but rather the nature of the display. Gentlemen Cadets of the  Other units were none the less efficient. The

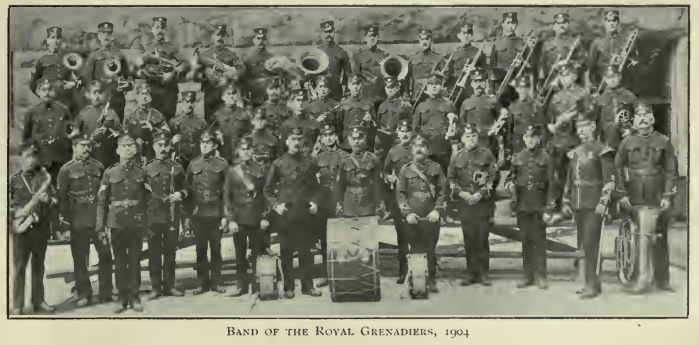

Other units were none the less efficient. The  "A" Squadron, Royal Canadian Dragoons, performed in a musical ride that was a spectacular item on the programme, perfect control of their fine mounts being shown at all times. This culminated in a charge with lowered lance and fluttering pennon. Under the leadership of Lieut. H.G. Jones, R.H. of C., selections were rendered by the massed bands. The musical drive of the

"A" Squadron, Royal Canadian Dragoons, performed in a musical ride that was a spectacular item on the programme, perfect control of their fine mounts being shown at all times. This culminated in a charge with lowered lance and fluttering pennon. Under the leadership of Lieut. H.G. Jones, R.H. of C., selections were rendered by the massed bands. The musical drive of the

To be fully effective, a leader needs three kinds of integrity: ethical, physical, and psychological. Each kind of integrity has an impact on the others, and all require self-care. Ethical integrity has to do with behaving in ways defined as good—telling the truth, taking care of one's troops, not ordering subordinates to do things one is not willing to do oneself. …

To be fully effective, a leader needs three kinds of integrity: ethical, physical, and psychological. Each kind of integrity has an impact on the others, and all require self-care. Ethical integrity has to do with behaving in ways defined as good—telling the truth, taking care of one's troops, not ordering subordinates to do things one is not willing to do oneself. …

"A few hours' rest, a feed and a few winks of sleep and Saturday, the ninth, began to dawn. Somewhat refreshed and a song of victory in our hearts once more we buckled on our armor; once more the incessant tramp, tramp, tramp as we followed closely upon the enemy, wondering and watching for our next encounter. Had he fled entirely? No shrieking of shells or twang of bullets pierced the air. A beautiful, fine morning dawned, and save for the distant roar of the guns on our flanks, the world seemed at peace. Too good to last, and soon we were awakened to realization of war once more. We were now close upon Hornu, which soon fell into our hands with scarcely a struggle, and so on to Ouaregnon with little resistance.

"A few hours' rest, a feed and a few winks of sleep and Saturday, the ninth, began to dawn. Somewhat refreshed and a song of victory in our hearts once more we buckled on our armor; once more the incessant tramp, tramp, tramp as we followed closely upon the enemy, wondering and watching for our next encounter. Had he fled entirely? No shrieking of shells or twang of bullets pierced the air. A beautiful, fine morning dawned, and save for the distant roar of the guns on our flanks, the world seemed at peace. Too good to last, and soon we were awakened to realization of war once more. We were now close upon Hornu, which soon fell into our hands with scarcely a struggle, and so on to Ouaregnon with little resistance.

It has become a settled conviction that the question of the statutory observance of Armistice Day and Thanksgiving Day was settled for all time by the adoption in 1921 of legislation which fixed the two events for the Monday in the week in which 11th November shall occur. November 11 was the date in 1918 on which the World War was concluded by an armistice.

It has become a settled conviction that the question of the statutory observance of Armistice Day and Thanksgiving Day was settled for all time by the adoption in 1921 of legislation which fixed the two events for the Monday in the week in which 11th November shall occur. November 11 was the date in 1918 on which the World War was concluded by an armistice.