Topic: The Field of Battle

The Somme

Incidents of the Battle

Sydney Doctors Story

The Sydney Morning Herald, Sydney Australia, 6 September 1916

In a letter to Mrs. Everard Digby, of Neutral Bay, a captain who is serving as a medical man in France gives a graphic description of the Somme battle. The letter is dated July 7. The captain writes:—

In a letter to Mrs. Everard Digby, of Neutral Bay, a captain who is serving as a medical man in France gives a graphic description of the Somme battle. The letter is dated July 7. The captain writes:—

"By now you have read of the British offensive on the Somme. Well, your elder son has been in it from the beginning, and is still all right, in spite of narrow shaves, and hopes to come along through it all right. This is what I've been waiting for for 12 months, and now I can rest contented; though I was through Ypres and the taking of the Bluff, which were exciting enough. I wanted something like this to put the crowning glory on things, and now I have got it. Three cheers.

"To tell you in detail all that led up to things would keep me writing till morning. How we got the order to move at last; the joy of everyone when we knew that at last we were 'for it' for the 'great push.' How we lightened our kit for the advance; the cleaning of revolvers, and, on my part the replenishing of dressings, drugs, splints, etc.; the seven days' march through cold and rain and mud, alternating with sunshine; marching all the time by night; the meeting of fresh troops, everyone cheery, thirsting to be up and at 'em; the bivouacing out in woods, fields, hedges—anywhere.

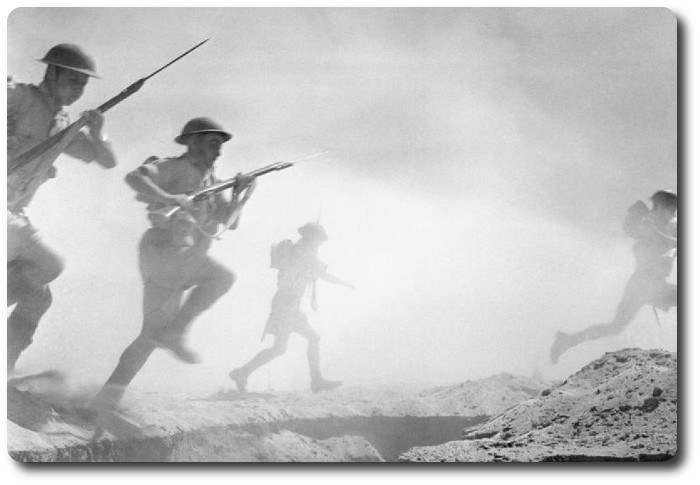

"I can begin telling you in some detail the course of events from the time my brigade came into action a week before the morning of the attack, July 1. In conjunction with the Tock Emmas, which were wire-cutting, our batteries were shelling Huns, preventing them from repairing their wire at night. We handed out condensed hades to Fritz, with a mixed diet of H.E. and shrapnel, day and night for a week, and I had remarkable luck, having only one man killed. The assault was timed for 7.30 a.m., and so at 7 a.m. you saw me, girt with glasses, smoke-helmet, and 'tin-hat,' lying behind a parapet on the top of a rise in rear of the firing line. The whole front was a mass of drifting blue smoke, stabbed with the red flashed of the bursting shells and the huge 'splash' of earth made by the H.E. of the heavy howitzers. The morning mist hung over everything, making observation difficult. However, with my watch in my hand, and my glasses glued to my eyes, I watched the front line. At 7.30 I saw the boys go 'over the top,' the sunshine flashing on their bayonets. The part of the line I was watching go across 'No-man's land' had very few casualties before they were into the Boche front line. Here things were hard to see, but the Boches rushed over the parados for their second line, followed by our boys, bayonetting and bombing. Parties of Huns here and there flung up their hands, and were taken prisoners. The fight then disappeared into the smoke and I lost sight of it. Farther to the north, where the smoke and shells were thinner, I could see five successive waves chase the Boche out of his four front lines of trenches, and then our lads, having carried this line, dug themselves in like rabbits. It was here I saw a very pretty bit of bayonet work in which the Boche came off second best.

"Having seen everything to be seen here I got back to my aid post among the batteries, and all the morning the wreck and wastage of war, the walking wounded cases, trailed past my aid-post to the collecting station at the end of the valley. I stopped several of them and asked how things were going, and they were all happy and pleased as Punch. I relate several little incidents that I saw and had related to me by the wounded. One man, hit in both legs and the head, came limping along. 'It's great, sir,' he said to me, 'to see half a dozen of these big ——-s chucking up their hands to our little fellows.' He was sorry to be out of it so soon, and he passed on with one of my cigarettes.

"Another man with a bullet wound through his hand grinned all over his face when I asked him how he got hit. 'Well, you see, it was this way. I saw an officer come out of a dugout with a revolver. I had a Mills, and I got it off first. You should have seen that officer. Mills! He was full of Mills. As I thought he would be useful for information, I carried him into the dressing station, and on the way I got hit … A Mills is a hand grenade, named after its inventor, or, as Ordnance calls it, 'Grenades, hand, Mills, one.' Incidentally, I might mention I used up all my available stock of cigarettes on our wounded. Poor devils, you can't do enough for our infantry!

"Then the prisoners started to arrive in batches of 10, 20, 50, 100, and in one case 250, the last bunch guarded by three Jocks. I had a good opportunity of studying them. They belonged to a reserve regiment, and were all men of about 40 or more. One Boche, a regular giant of over seven feet, and hands like a leg-of-mutton, had his elbow shattered by a trench mortar, and was nearly collapsing as he was marched along, so the escort asked me to fix him up. So I tied him up and gave him a nip of brandy and a cigarette, whereupon he assailed me with a volley of Hun language and tried to shake hands, so I suppose he was trying to thank me. As I don't know any Hun, I simply asked 'Goot?' He 'yah-yahed' away like blazes. You can't help pitying them when you see them in that condition.

"In one batch of prisoners was one of the German medical service with a Red Cross brassard on his arm. As he passed me he pointed to my brassard and grinned like a Cheshire cat and said 'Kamerad.' I never felt so insulted in my life, especially as the tommies laughed. Among the first lot of prisoners were a fair number of wounded, but the later lots were all pretty sound.

"The prisoners were all marched into a barbed wire cage before being sent on to the bigger concentration camps, and here they were searched.. One Hun had an Iron Cross in his pocket-book, and this was a subject of great interest. Most of these prisoners had had nothing to eat for three days, as our bombardment prevented them getting food up, and they picked up bits of biscuit and bread and sucked empty beef tins as they went along. One, standing close to me, asked if I could speak French, and, on my saying I could, launched forth in a long yarn. He told me he was an Alsatian, and all about the battle from his point of view. So I yarned to him for about an hour, and gave him my last cigarette. I asked him what he thought of our troops, and he said they were all right, but the Scotch regiments were known among the Germans as the 'Mad Women from hell.' One of the escort on duty at the cage had an automatic pistol, and when asked where he'd got it, replied, 'From a German officer." 'And where's the officer?' asked the officer in charge' 'Oh, I bayoneted him,' was the reply, and, judging from the blood on his bayonet, I have no doubt he did.

"Later on I went over the captured ground up to within a few hundred yards of our new firing line. Passing over 'No Man's land,' where several of our lads were still lying awaiting burial, I passed into the Hun front lines. All his wire had been cut to small pieces by the combined fire of 18-pounders and trench mortars, and the heavy howitzers had got on to the trenches themselves. I never saw such a wreck. The trenches were only a succession of crump holes. The German dead lay piled up in heaps, two, three, and four deep, having met their death from bullet, bomb, bayonet, and shell fire. I won't dwell in detail on the ghastly sights I saw at every step, but they were a speaking expression of the horrors of war.

"The dug-outs are marvellous pieces of work—deep down under the parapet—and no shell made can reach anyone down there. I went into several in fear and trembling, because in many cases Huns were found in them two days after the attack still alive and full of fight. The ones I entered were only occupied by dead, as our fellows, as soon as they got the Huns in their dug-outs, bombed them and slaughtered them like rabbits. All along the trenches the same thing had happened—crunped trenches, dead Huns, and dug-outs full of dead. As for souvenirs, for those who wanted them, they were there in any quantity—helmets, rifles, bayonets, cartridges, badges, buttons, etc. I contented myself with a button, a clip of cartridges, and a plying card I found in a dug-out, and which I enclose.

a. The use of information provided by PWs and

a. The use of information provided by PWs and

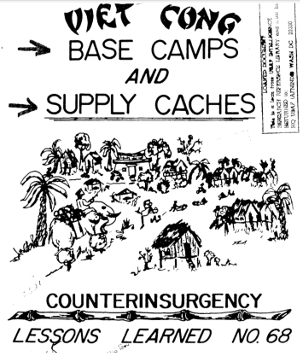

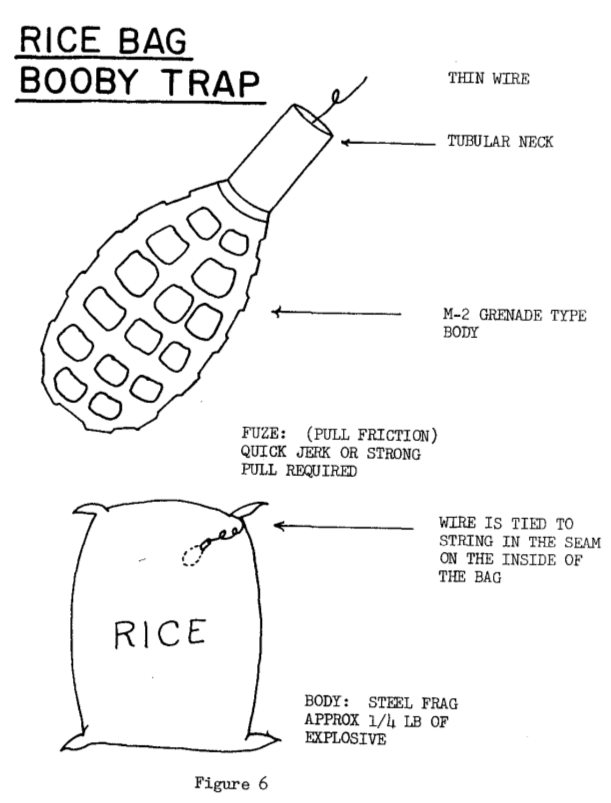

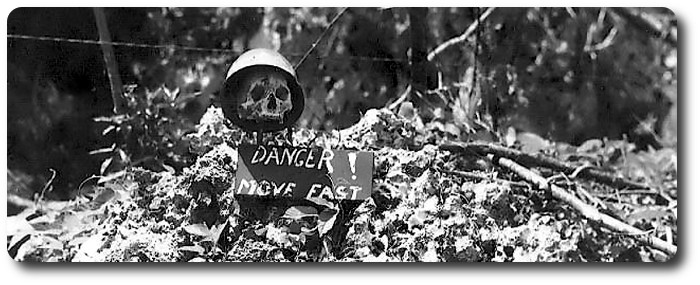

The war in Vietnam is a small unit leader's war. Because of the large number of semi-independent platoon and company missions performed by units in Vietnam, the knowledge and skill of the small unit leader are more important than ever before. Some of the lessons learned by small unit commanders are discussed below.

The war in Vietnam is a small unit leader's war. Because of the large number of semi-independent platoon and company missions performed by units in Vietnam, the knowledge and skill of the small unit leader are more important than ever before. Some of the lessons learned by small unit commanders are discussed below.

The Montpelier, Idaho, infantryman said later, "I felt something hit me on the arm. I thought it was the squad leader jabbing me.

The Montpelier, Idaho, infantryman said later, "I felt something hit me on the arm. I thought it was the squad leader jabbing me. The interdependence of men, especially in jungle warfare, has wrought what one officer called a revolutionary change in race relations in the military. Vietnam is the first war in which all U.S. units are thoroughly integrated.

The interdependence of men, especially in jungle warfare, has wrought what one officer called a revolutionary change in race relations in the military. Vietnam is the first war in which all U.S. units are thoroughly integrated. Earlier in the war, a U.S. 101st Airborne company was commanded by a Negro captain from Atlanta, Ga. The captain was articulate, well;-educated and very much the commander of his men.

Earlier in the war, a U.S. 101st Airborne company was commanded by a Negro captain from Atlanta, Ga. The captain was articulate, well;-educated and very much the commander of his men.

A day after he should have left Khe Sanh, the sergeant finally got his orders. His friends congratulated him. Home, today he was starting home.

A day after he should have left Khe Sanh, the sergeant finally got his orders. His friends congratulated him. Home, today he was starting home. A few hours later a Marine CH46 helicopter began spiraling down with a full load of replacements, men just starting their Vietnam tour.

A few hours later a Marine CH46 helicopter began spiraling down with a full load of replacements, men just starting their Vietnam tour.

If

If

Out into the dark night the Shropshires sent a heavy picket with instructions to the men to be very careful to challenge every person who might come in or out of camp. At the foot of a kopje one of the men of the Shropshires stood on sentry, another private of the same regiment was returning to camp. The sentry promptly challenged, "Halt! who comes there?" and failing to call "Friend," the returning soldier said, "Oh, to you know me." These were fatal words, for no sooner had they been spoken when three ringing shots sounded through the Orange River garrison, three steady shots from the sentry's rifle, and his companion-in-arms fell, never to rise to life again. It was an unfortunate occurrence which cast gloom over the whole camp, but it shows that the rigidity of military discipline should not be trifled with.

Out into the dark night the Shropshires sent a heavy picket with instructions to the men to be very careful to challenge every person who might come in or out of camp. At the foot of a kopje one of the men of the Shropshires stood on sentry, another private of the same regiment was returning to camp. The sentry promptly challenged, "Halt! who comes there?" and failing to call "Friend," the returning soldier said, "Oh, to you know me." These were fatal words, for no sooner had they been spoken when three ringing shots sounded through the Orange River garrison, three steady shots from the sentry's rifle, and his companion-in-arms fell, never to rise to life again. It was an unfortunate occurrence which cast gloom over the whole camp, but it shows that the rigidity of military discipline should not be trifled with.