The Burthen and the Brunt

A Short Description of the Service of the British Regular Army in Canada

By Colonel G. R. Pearkes, V.C., D.S.O., M.C., p.s.c., P.P.C.L.I.

Canadian Defence Quarterly, Vol. XII, No. 4, July, 1935

Historical Sketch

The British claim to the sovereignty of North America dates from the reign of Henry VII, under Whose distinguished patronage Sebastian Cabot made his great discoveries, but it was not until 1621 that the first colony was planted in what is now the Dominion of Canada. In that year Sir William Alexander obtained a grant of land from James I of the territory which he christened Nova Scotia. At the same time other English emigrants were founding the New England colonies. In the course of years the English settlements in North America multiplied rapidly, and by the close of the reign of Charles II the British seaboard extended from the Savannah to the Kennebec.

During this time French influence had spread along the St. Lawrence and Richelieu Valleys. Westward as far as Lakes Superior and Michigan they had taken possession of vast tracts of land wherever their missionaries or traders had penetrated. To secure these lands the French constructed a chain of forts at strategic points. The monopoly of the Indian trade thus established led to bitter conflict which lasted with little intermission for many years.

Until the beginning of the reign of George I the British colonies were expected to raise their own militia, and to provide the defence of their newly acquired homes. But this primitive method of colonial defence broke down as soon as the French sent regular troops as permanent garrisons for the forts that had been established. The English in turn were thus forced to provide garrisons for their own frontier posts. To man these in times of emergency, independent companies of regulars were stationed at important points; sometimes these were colonial troops; sometimes soldiers sent from England; but since the colony had to provide for the maintenance of these troops, they were never retained longer than could be helped.

The colonial service at this time was far from popular. Recruits could only be obtained when large bounties were offered. This practice proved costly to the British Government, and encouraged the crimps to kidnap men who were subsequently spirited across the Atlantic. Frequently the drafts were filled with criminals. Sometimes pensioners and "invalids"—soldiers who were incapable of active service but still judged fit for garrison duties—were sent out in place of recruits. As a result of these methods the men were discontented and miserable—the companies filled with bad characters.

Independent companies as well as colonial regiments took part in the numerous Indian wars and raids against the French. Many of these early expeditions had a direct bearing upon the course of events in Canada, but they do not come within the scope of this article since regiments of the British Army took no part in them.

The first expedition in which regiments that still exist in the Army List were employed was that which, led by Colonel Nicholson, captured Port Royal in July, 1710, and changed its name to Annapolis Royal. The regiments concerned were the 30th, or East Lancashire Regiment, and the Duke of Cornwall's Light Infantry. [Footnoted: "Modern titles are used throughout this article."]

Nova Scotia had changed hands many times, but henceforth it was to remain British, and for the next two hundred years British regulars provided the garrisons for its posts.

Immediately after his success at Port Royal, Colonel Nicholson returned to England to urge the government to continue in its determination to drive the French from North America. In the spring of 1711 a powerful fleet was placed under the command of Admiral Hovenden Walker, and five regiments were withdrawn from Marlborough's army for an expedition against Quebec. How the fleet became lost in a fog in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, and the transports dashed to pieces on the rocks of Egg Island, with the loss of over 700 lives, is probably known to most readers. The regiments that took part in that ill fated expedition were:—

- The Queen's Royal West Surrey Regiment.

- The King's Own Royal Regiment (Lancaster).

- The Devonshire Regiment.

- The Worcestershire Regiment.

- The Hampshire Regiment, and

- Two regiments that have since been disbanded.

Before these regiments returned to England, each left one company to augment the garrisons of Nova Scotia and Newfoundland.

In 1717 these companies, together with the independent companies of the East Lancashire Regiment and the Duke of Cornwall's Light Infantry, were merged into one corps to be numbered the 40th Foot, now the Prince of Wales's Vounteers (South Lancashire). Though given a place in the line, the regiment was still considered a colonial garrison and, therefore, unremovable. It remained continuously on service in Nova Scotia until 1765. It is now affiliated with the Annapolis Regiment and the Princess of Wales' Own Regiment of Kingston.

The War Office was slow to recognize its responsibilities in connection with the maintenance of this new regiment. The fortifications at Annapolis Royal were allowed to decay, and by 1730 the barracks were falling down. In vain the officers of the regiment begged for blankets and supplies. The feeding of the garrison of Nova Scotia was entrusted to contractors, but in the contracts the most obvious necessities were overlooked. In a letter dated 25th May, 1727, Governor Phillips wrote to the Lords of Trade complaining about the condition of the troops at Annapolis Royal, stating "everything here wearing the face of ruin and decay, and almost every countenance despair". He described the ramparts of the fort as "lying level with the ground, in breaches sufficiently wide for fifty men to enter abreast, which obliges the garrison to insupportable duty to guard against their throats being cut by surprise."

The assault on Louisburg in 1745 was carried out by provincial troops. The fall of the fortress, however, encouraged the British Government to complete the conquest of Canada and, accordingly, they despatched three regular regiments—the Worcestershires, East Lancashires, and the Sherwood Foresters—to relieve the colonial garrison at Louisburg, and to prepare for a campaign against Quebec. The latter part of this plan came to naught, and the regiments remained to do garrison duties. When Louisburg was restored to the French by the Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1749 the garrison was transferred to other posts. The Worcestershire Regiment sailed to Chebucto Bay where it cleared the ground on the site of the present city of Halifax.

But peace brought no security. Fighting continued in Arcadia. Fort Beauséjour was destroyed and rebuilt as Fort Cumberland by the Gloucesters. Elsewhere British troops were heavily engaged against the French and their Indian allies. The Essex and the Northamptonshire Regiments were annihilated before Fort Duquesne. The Black Watch, the Border Regiment and the Inniskilling Fusiliers fell before the stockades of Ticonderoga. The 2nd Battalion of the King's Royal Rifle Corps and a detachment of Royal Artillery captured Fort Frontenac (Kingston) in 1758—they were the first British troops to reach Ontario. Ten regular regiments besieged Louisburg. Wolfe led his army of regulars to Quebec where the grenadiers lost heavily on the slippery slopes of Montmorency. The regiments still retained in the Army List that fought at Quebec are the East Yorkshires, Gloucesters, The Royal Sussex (which has incorporated the white feather of the Royal Roussillon Regiment in its badge), The Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry, The Loyal Regiment (North Lancashire), both battalions of the Northamptonshire Regiment and the King's Royal Rifle Corps. Fraser's Highlanders, which played a prominent part in the Battle of the Heights of Abraham, was disbanded at the close of the war.

The capture of Quebec was but the fall of a fortress, not the conquest of Canada, and the victors were themselves besieged during the winter of 1759 when the troops suffered terribly from frost bite.

After the Battle of St. Foy, the situation was critical, until reinforcements arrived with the opening of navigation. Then the columns converged upon Montreal—Amherst with the Royal Scots and five other regular regiments sailing down the St. Lawrence from Oswego: the Leicesters and Inniskillings marching from Crown Point, and the Quebec garrison advancing up the St. Lawrence. Two years later the Great Indian War broke out when the tribes under Pontiac, the Chief of the Ottawas, surprised detachment after detachment of the King's Royal Rifle Corps in the trading posts that stretched from Montreal to Lake Superior—Detroit alone held out.

After the Peace of 1764, regiments were withdrawn from Canada to meet the more menacing situation in the West Indies and the older colonies. When war broke out again in 1775 only three regiments remained in Canada; The King's Regiment (Liverpool) in the west, and the Royal Fusiliers and the Cameronians in Lower Canada. The Americans advanced up the water route of Lake Champlain-Richelieu River to St. Johns where a few companies of the Royal Fusiliers and the Cameronians withstood a siege by 4,000 Americans until 2nd November when their provisions and ammunition became exhausted. The delay thus caused to the invaders saved Canada, for though Montgomery took Montreal and joined Arnold at Quebec, winter conditions and the fact that most of the American volunteers had completed their service helped to defeat the invaders just as much as the heroic efforts of the defenders.

The Surprise with the Worcestershire Regiment on board arrived with the opening of navigation. It was the van guard of Burgoyne's army of 10,000 regulars, and during the summer of '76 they, in conjunction with the King's—the light company of which under Captain Forster fought a notable engagement at the Cedars near the junction of the Ottawa and St. Lawrence rivers—cleared the country of the enemy. In the following year Burgoyne marched with his regulars south to Saratoga only to find that a cashiered officer, who had become Secretary of War, had failed to make the necessary arrangements for co-operation with the forces in New York. As far as Canada was concerned, the rest of the war was a campaign of raids and surprises.

After the American War of Independence the military situation in Canada changed completely. Up to this period the campaigns had been fought almost entirely by British regular regiments, but with the influx of the United Empire Loyalists, and the other settlers, the population of Canada increased enormously. Many of these settlers were ex-soldiers, in some cases complete regiments settled in localities with the result that militia units were formed, and although regulars from the Old Country still provided the garrisons at important points the next war was fought largely by Canadian troops, the regulars providing a backbone around which the militia rallied.

We thus find that when war broke out in 1812, although a few regular units, such as the Welch, the King's and the Royal Berkshire regiments, were stationed in Upper Canada, the bulk of the forces were supplied by Canadian troops.

The militia, however, at this period were poorly trained, and the militia officer was little more than a recruiting agent who mustered his men and marched them to the nearest post, there handing them over to such officers as the Governor-General appointed, by these to be trained and fought.

After the War of 1812 it was still necessary to maintain military garrisons in Canada. During the Fenian Raids and the Rebellions of 1837-38 new garrisons were established in Upper Canada, as for instance, that of London, where the Duke of Cornwall's Light Infantry was first stationed in 1838.

In 1846 the Royal Warwickshire Regiment, the first body of troops to reach the North West, landed at York Factory on the Hudson Bay and traversed the 375 miles to Fort Garry (Winnipeg) carrying with them three 6-pdr. brass guns.

Pte. O'Hea of the Rifle Brigade was awarded the only Victoria Cross ever gained in Canada. Between Quebec and Montreal, on 6th June, 1866, at great personal risk he extinguished a fire that had broken out in a railway car loaded with ammunition.

The last campaign in which British regular troops took part in Canada was the Red River Expedition, when the King's Royal Rifle Corps went to Fort Garry. After sailing across Lake Superior and establishing a post at what is now Port Arthur, they cut their way through the forests to the Lake-of-the-Woods and thence proceeded by canoe to Fort Garry. After this British troops took no part in any active operations in Canada—except that they provided commanding officers and staffs for the Riel Rebellion Expedition of '85—but they still remained as garrisons at Halifax and Esquimalt. The last regiment of the line to be stationed in Halifax was the 1st Battalion The Leinster Regiment, which was there at the outbreak of the South African War. It was relieved temporarily by the 3rd (Special Service) Battalion of The Royal Canadian Regiment, as a Canadian contribution towards the war. In September, 1903, The Royal Canadian Regiment was relieved by the 5th Battalion Royal Garrison Regiment, which with the gunners and sappers remained for a few years longer, but in 1906 Canada took over for all time the defences of her seaboard ports.

Organization

Prior to the middle of the 18th century regiments were known by their Colonel's name, e.g., "Webb's", "Lascelles'", and "Otway's", unless they possessed a permanent title such as the "Royal Highlanders" or the "Royal American Regiment". Numbers were seldom quoted in official correspondence, though they were employed to denote precedence in rank. In the 19th century numbers were used entirely until the territorial designations were authorized.

The majority of regiments consisted of one battalion of ten companies, in a few cases, two or more battalions of a regiment were formed. Of the ten companies in each battalion one consisted of grenadiers and one of light infantry. Although grenades were not usually carried except for siege operations, the grenadier companies remained and were composed of the tallest and strongest men. The light infantry companies were introduced, largely upon the instigation of Sir William Howe, to provide each battalion with a body of picked marksmen to act as skirmishers. They carried a special kind of musket, which was lighter than that used by the other companies. During an engagement the grenadier and light infantry companies were usually placed on the flanks of the battalions, and hence became known as the "flank companies". Later, the practice of "brigading" the flank companies into special battalions was adopted. For example: Wolfe formed the Louisburg Grenadiers from the grenadier companies of the regiments left behind to garrison Louisburg when he sailed for Quebec. In 1812 a Flank Battalion under Colonel Robert Young of the 8th Foot was composed of the flank companies of several regiments. Many other illustrations of this sort might be given.

Consequent upon the difficulty of shipping horses, few British cavalry regiments served in Canada. The 19th Light Dragoons, now the 19th Royal Hussars (Queen Alexandra's Own) which saw more service here than any other cavalry regiment, was organized into six troops of three officers and 42 rank and file.

Companies of the Royal Artillery were grouped together into battalions when there were sufficient companies to justify such action. A company at full strength consisted of a captain, and 116 all ranks. This establishment included no drivers, as the drivers in the artillery were hired from civilian sources and were looked upon as servants of the contractors from whom the government hired horses. The field guns usually consisted of 6- and 3-pounder field pieces; the former drawn by four and the latter by three horses. The 3-pounders were sometimes mounted on light carriages, known as Congreve carriages, which made it possible to carry them on the backs of horses or mules in difficult country. It was customary to detail two guns to an infantry battalion, and these were known as "battalion guns". This practice was criticized by some officers because it prevented concentrations of artillery fire. Burgoyne seems to have abandoned it, marshalling his field guns into three "brigades". As each brigade only consisted of four 6-pounders, it would be more the equivalent of a modern battery rather than a brigade. In addition, Burgoyne took with him a park of heavy guns, howitzers, and mortars, 12- and 24-pounders, to reduce block houses erected by the Americans and to clear away abatis.

The infantry, cavalry and artillery, constituted the three most important branches of the army. There were in addition to these a company of military artificers and a small but efficient corps of engineers. The former saw no service in Canada, but several officers of the latter did excellent work during the American Wars. Towards the close of the 19th century companies of sappers were stationed at Halifax and Esquimalt. Artificers are occasionally mentioned as participating in the American campaigns but they were not members of the company mentioned above. In some cases they were probably civilians who were hired to serve with the army as masons or carpenters. In others they were doubtless privates with a knowledge of the building trades.

Supply, transport and other services were in an embryonic state. Batteaux brigades were organized by Colonel Clarke in 1812, batteaux being flat bottomed boats of light draught but carrying heavy cargoes. By dint of rowing, towing, punting, or dragging by ropes, these were forced up the rapids. The crews were supplied by a corvee of French Canadians. The corvee was also used to open the King's Highway. Authorities were apt to impress every man and vehicle on the route and to stop at nothing to get the brigade through to its destination. During the War of 1812 practically everything, arms, ammunition, clothing and food for the troops in Upper Canada had to be sent from Montreal. The soldier's ration was mostly salt pork and "pilot bread" or ship's biscuit manufactured in Portsmouth.

No Medical Corps, in the modern sense of the term, existed. A surgeon and mate were attached to each regiment of Foot. They were. however, essentially regimental officers, appointed by the colonel whose servants they had originally been. The surgeons were not required to hold a medical diploma or degree, nor the mate to pass a medical examination. Nurses were sometimes obtained among the women who followed the army, it being the custom to permit women to accompany the troops to Canada where the government rationed them. In the field only a fixed number of women were allowed. Army doctors laboured under many other disadvantages beside ignorance and inexpert assistance. They were poorly paid and although given a certain allowance for medicine, they had to provide their own surgical outfits. They were not allowed uniforms, and occupied an inferior social status among the other commissioned officers.

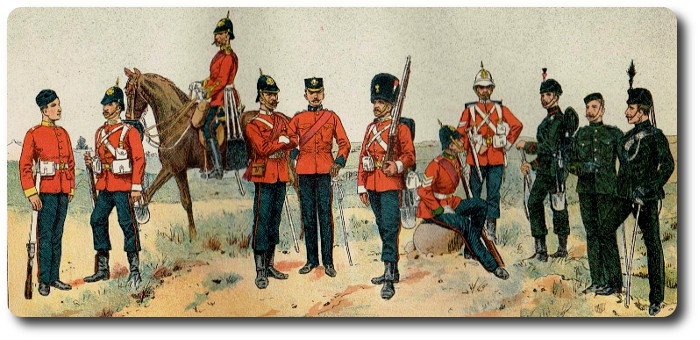

Uniform

The uniform of a private soldier was ill adapted for comfort and speedy movement. In the majority of regiments in the 18th century it consisted of the familiar red coat—the voluminous folds of which were buttoned back to form lapels—stock, waistcoat, smallclothes, gaiters reaching just above the knee, and cocked hat. Ordinary regiments had facings each of a particular colour—yellow, green, buff, white, red, black or orange, and for royal regiments, blue. Bandsmen were dressed in the colour of the regiment's facings. Officers and men wore the hair clubbed, that is, plaited and then turned up and tied with tape or ribbon. In case the supply of hair on a man's head was insufficient, he was obliged to eke it out with a switch. Over his left shoulder the foot soldier wore a broad belt supporting a cartouche box, while another belt around his waist supported a bayonet and short sword. On service the infantryman also carried a blanket, a haversack with provisions, a canteen, a fifth share of the general equipage belonging to his tent, and a knapsack containing extra clothing, brush and blackball. These articles added to his accoutrements, arms, and sixty rounds of ammunition, made according to Burgoyne, "a bulk totally incompatible with combat and a weight of about sixty pounds".

The Dragoons were armed and clad very much like the Foot, except that they wore high boots and carried pistols and long swords. Being regarded as a species of mounted infantry, they also carried firelocks.

The uniform of the artillery consisted of a blue coat, cocked hat, white waistcoat, white breeches, and black spatterdashes. Sergeants carried halberds, but corporals, bombardiers, gunners and matrosses were armed with carbines and bayonets.

In every branch of the service the uniforms of the officers were similar to those of the men. They wore sashes of considerable length and breadth. which served as a kind of slung stretcher for carrying the owner off the field in case he were wounded. The most striking feature of the officer's uniform was the gorget. Originally this was a large steel plate designed to protect the throat but with the abandonment of medieval armour it had shrunk in size until at the time of George III it was purely ornamental, being simply a small plate—often of gold—hung about the neck in front and bearing the regimental badge.

Arms

The British regular during the greater portion of his service in Canada was armed with the "Brown Bess". This was a smooth bore flintlock musket with a priming pan, three feet, eight inches long in the barrel, and weighing fourteen pounds. It had an effective range of 300 yards, but its accuracy was unreliable at a distance greater than 100 yards. At a distance of over 100 yards the firing line during an engagement relied not so much upon the shooting of each individual as upon the general effect of the volleys it delivered. The missile used in the Brown Bess was a round leaden bullet, weighing about an ounce, and made up with a stout paper cartridge. In loading, the soldier first tore the end off the cartridge with his teeth, then sprinkled a few grains of powder from it into the priming pan, and finally rammed the ball and cartridge down the muzzle of the barrel with an iron ramrod. Although twelve separate motions were required, it is said that a clever marksman could load and fire a Brown Bess five times a minute. The average soldier, however, fired only two or three rounds a minute. The bayonet, which weighed over a pound, and was about fourteen inches in length, did not increase the accuracy of shooting.

With bayonets fixed to the muzzle only one effective round could be fired, since the bayonet made it difficult to ram down the charge. Sometimes powder and ball were put in without ramming, then the effect was of course slight. Rapid firing was not considered as very essential. "There is no necessity", wrote Wolfe, "for firing very fast; a cool, well levelled fire, with the pieces carefully loaded, is more destructive and formidable than the quickest fire in confusion".

Another firearm in use was the "fusil" which was a musket of less than ordinary length and weight. It was supplied to light companies and fusilier regiments.

Long before rifled flintlocks were officially adopted by the regular army, colonels supplied them to one or two good shots in their regiments; and before the close of the American War of Independence, every battalion in Canada had organized a rifle company. Aside from their clumsiness the firearms of the period had one very serious drawback: their efficiency was dependent upon the weather. A high wind might blow the powder out of the pans. If a man was shooting towards the wind he had to take precautions against getting his face scorched and his eyes injured by the back blown flare from the touch-hole. A rainstorm might either wash the powder out of the pans or dampen it so that it failed to ignite. If sufficiently heavy and prolonged, a downpour of rain might soak through the cartouche boxes and turn every cartridge into pulp. Thus the assault of the grenadiers at Montmorency in 1759 was stopped by a thunderstorm. During the siege of Louisburg the troops were cautioned that since the air of Cape Breton was moist and foggy they must be especially careful to keep their firearms dry. Quaintly the commander added, that "the light infantry should fall upon some method to secure their arms from the dews and droppings of the trees when they are in search of the enemy".

Under any circumstances the marksmanship in most regiments was poor. Scant mention is made of target practice, and the inference is that there was little of it, although regiments were repeatedly exercised in firing by platoons. It has been claimed that the soldiers did not aim at anything in particular. This probably accounts for the saying that "it took a man's weight in bullets to kill him". These conditions gave rise to the sharpshooter, a man who not merely discharged his musket, but aimed it at something or somebody.

The Royal American Regiment, or 60th Foot, now the K.R.R.C., was created "to form a body of regular troops capable of contending with the Red Indian in his native forest by combining the qualities of the scout with the discipline of the trained soldier." Officers trained in the school of European warfare, however, were prone to place more reliance upon the bayonet than upon the bullet. Burgoyne in particular, urged his men to use the bayonet: "Men of half (your) bodily strength and even Cowards may be (your) match in firing; but the onset of Bayonets in the hands of the Valiant is irresistible. … It will be our glory and preservation to storm where possible."

The sword was not the weapon of the officers in all cases. Infantry officers carried spontoons, or half-pikes, and sergeants bore halberds. The latter were about seven feet in length, and had a cross piece near the point to prevent overpenetration after a thrust.

The woody character of the country in Canada induced many of the officers to discard these awkward medieval weapons and to replace them by firelocks. Fusils were carried by all officers of the Royal Fusiliers and by certain officers of the grenadier and light companies of some other regiments.

Conclusion

Proudly they marched, horse, foot, and guns. Four cavalry regiments, numerous companies of artillery, in fact, the Royal Regiment of Artillery served continuously in Canada from the middle of the 18th century until the garrisons at Halifax and Esquimalt were finally transferred to the Dominion. Three regiments, the Grenadiers, Coldstream and Scots, of the Brigade of Guards, and with but two exceptions every line regiment were represented in Canada. They fought gallant and determined foes; individuals fell to the tomahawk of the Indian, were scalped, burnt or tortured to death. Many units experienced shipwreck on the high seas. A detachment of the North Staffordshire Regiment, for instance, while travelling in the barque Alert struck a rock 100 miles southeast of Halifax. The ship began to fill rapidly, and carried away by their first impulse, the troops rushed to the upper deck. There they fell in, and in order to prevent the ship foundering, returned to the lower deck, where they stood firm while the water rose slowly from their ankles to above their knees, until the ship was beached on a small uninhabited island. Hundreds of men perished when their whale boats or batteaux were smashed to pieces in the rapids of the St. Lawrence or the Richelieu rivers. On the 4th September, 1760, Amherst lost 66 boats and 84 men drowned in the passage of the Cedars and Cascades on the St. Lawrence above Montreal. Many ships were lost on the Great Lakes. Cholera, scurvy and frostbite all took their toll. St. Johns, P.Q., was reported upon at one time as being the most unhealthy station in the British Empire. Annapolis as the loneliest and dullest. Forts built by British regiments still dot the Canadian landscape. British soldiers have cleared the original sites of many Canadian cities. They opened up the country, built roads and dug canals. The King's Highway from Montreal to Toronto, the old military pack road through the Restigouche, and the Cariboo Trail through British Columbia are but a few examples of their work.

Many soldiers took their discharge in Canada and became settlers in the early pioneer days. Sometimes whole companies were disbanded and established communities from which their sons and grandsons responded to the call to arms when the Empire was in danger.

The 100th County of Dublin Regiment provides a striking example of this, for that regiment, on disbandment at the conclusion of the War of 1812, established a settlement at Richmond near Ottawa. From the sons of these ex-soldiers the 100th Prince of Wales's Royal Canadian Regiment was recruited at the time of the Indian Mutiny. The Regiment had its depot in Canada for a number of years, and eventually became the 1st Battalion Leinster Regiment (Royal Canadians).

The history of the British army in Canada is the history of Canada. The Dominion owes much to the initiative, daring and perseverance of the regular soldier who at all times has proved himself to be a great Empire builder.

- The O'Leary Collection; Medals of The Royal Canadian Regiment.

- Researching Canadian Soldiers of the First World War

- Researching The Royal Canadian Regiment

- The RCR in the First World War

- Badges of The RCR

- The Senior Subaltern

- The Minute Book (blog)

- Rogue Papers

- Tactical Primers

- The Regimental Library

- Battle Honours

- Perpetuation of the CEF

- A Miscellany

- Quotes

- The Frontenac Times

- Site Map

QUICK LINKS

- Tomb of the Unknown Soldier

- Vimy Memorial

- Dieppe Cemetery

- Perpetuation of CEF Units

- Researching Military Records

- Recommended Reading

- The Frontenac Times

- RCR Cap Badge (unique)

- Boer War Battles

- In Praise of Infantry

- Naval Toast of the Day

- Toasts in the Army (1956)

- Duties of the CSM and CQMS (1942)

- The "Man-in-the-Dark" Theory of Infantry Tactics and the "Expanding Torrent" System of Attack

- The Soldier's Pillar of Fire by Night; The Need for a Framework of Tactics (1921)

- Section Leading; A Guide for the Training of Non-Commissioned Officers as Commanders and Rifle Sections, 1928 (PDF)

- The Training of the Infantry Soldier (1929)

- Modern Infantry Discipline (1934)

- A Defence of Close-Order Drill (1934): A Reply To "Modern Infantry Discipline"

- Tactical Training in the British Army (1901)

- The Promotion and Examination of Army Officers (1903)

- Discipline and Personality (1925)

- The Necessity of Cultivating Brigade Spirit in Peace Time (1927)

- The Human Element In War (1927)

- The Human Element In Tanks (1927)

- Morale And Leadership (1929)

- The Sergeant-Major (1929)

- The Essence Of War (1930)

- Looks or Use? (1931)

- The Colours (1932)

- Personality in Leadership (1934)

- Origins of Some Military Terms (1935)

- Practical Examination; Promotion to Colonel N.P.A.M. (1936)

- Company Training (1937)

- Lament Of A Colonel's Lady (1938)

- Morale (1950)

- War Diaries—Good, Bad and Indifferent

- Catchwords – The Curse and the Cure (1953)

- Duelling in the Army

- Exercise DASH, A Jump Story (1954)

- The Man Who Wore Three Hats—DOUBLE ROLE

- Some Notes on Military Swords

- The Old Defence Quarterly (1960)

- Military History For All (1962)

- Notes for Visiting Generals (1963)

- Hints to General Staff Officers (1964)

- Notes for Young TEWTISTS (1966)

- THE P.B.I. (1970)

- Standing Orders for Army Brides (1973)

- The Time Safety Factor (1978)

- Raids (1933)

- Ludendorff on Clerking (1917)

- Pigeons in the Great War

- Canadian Officer Training Syllabus (1917)

- The Tragedy of the Last Bay (1927)

- The Trench Magazine (1928)

- Billets and Batman (1933)

- Some Notes on Shell Shock (1935)

- Wasted Time in Regimental Soldiering (1936)

- THE REGIMENT (1946)

- The Case for the Regimental System (1951)

- Regimental Tradition in the Infantry (1951)

- The Winter Clothing of British Troops in Canada, 1848-1849

- Notes On The Canadian Militia (1886)

- Re-Armament in the Dominions - Canada (1939)

- The Complete Kit of the Infantry Officer (1901)

- The Canadian Militia System (1901)

- The Infantry Militia Officer of To-day and His Problems (1926)

- Personality in Leadership (1934)

- British Regular Army in Canada

- Battle Honours (1957)

- Defence: The Great Canadian Fairy Tale (1972)

- The Pig (1986)