Soldier Load; When Technology Fails (1987)

Major Richard J. Vogel, Major James E. Wright, Lieutenant Colonel George Curtis

Infantry, Vol. 77, No. 2, March-April 1987

As most infantrymen today will agree, an infantry soldier's ability to fight is directly related to his load, and there is a maximum individual load limit that cannot be exceeded if that soldier is to accomplish his combat mission.

Soldier loads do represent a serious problem; they always have. While technology has reduced the weight of many single items, it has been unable to reduce the overall weight the individual soldier has to carry into combat. As a result, U.S. infantrymen are more heavily burdened today than the soldiers in the ranks of the Roman legions some 2,000 years ago. (See "The Soldier's Load," by Major General Edwin H. Burba, Jr., Commandant's Note, INFANTRY, May-June 1986, pages 2-3.)

Although analysts and technicians continue to research and test lighter equipment and clothing, technology will never furnish more than a partial solution to the problem. For example, when the Army replaced the 7.62mm M14 rifle with the 5.56mm M16 rifle, it achieved thereby a weight reduction of some four pounds. But because the 5.56mm round of ammunition weighed less than the 7.62mm round, infantry leaders insisted that their soldiers carry more rounds. As a result, the net weight reduction of the rifle and its ammunition turned out to be negligible.

We spend millions of dollars reducing the weight of our soldiers' clothing by using nylon and Gore-Tex, and then our combat leaders negate that reduction by having their soldiers carry additional M16 or M18 mines, extra water, and even more ammunition. And some high-technology devices such as night vision aids will continue to add weight.

Load Planning

Regardless of technology, then, leaders tend to load their soldiers too heavily, primarily because current unit SOPs represent worst-case planning instead of educated-risk analysis.

Today, the Infantry School's Light Infantry Task Force has identified these primary areas of concern in the soldier load problem and is working with the Army Development and Employment Agency (ADEA) and the Soldier Physical Fitness School (SPFS) on some possible solutions.

In its approach, the Infantry School is paying particular attention to the important roles proper load planning and physical conditioning play in fielding combat ready soldiers.

Load planning has two purposes. First, it allows commanders to use METT-T and the estimate of the situation to determine how much ammunition and what kinds of equipment are necessary for a given mission. Secondly, it recognizes the soldier load problem and requires a commander to emphasize preparing his soldiers to carry the prescribed load and, when possible. to use his available transportation assets to help move that load.

On the basis of previous research and combat experience, the Infantry School has established the following goals for the weight to be carried by infantrymen: 45 percent of a soldier's body weight on approach marches (for the average soldier. about 72 pounds), and 30 percent (about 48 pounds) as a tactical load in a combat zone.

These weights are not absolute, of course. Leaders must be aware that a well-conditioned 160-pound soldier will be able to carry more than a poorly conditioned 200-pound soldier, The key point is that some men are stronger than others. Squad and platoon leaders should know the physical condition of their men and adjust their loads accordingly.

Leaders must recognize, however, that physically preparing the soldier can only do so much. A leader may be able to improve his soldiers' ability to carry loads on approach marches, but their fighting loads must be reduced to the bare minimum in combat. Otherwise, their ability to fight successfully can be seriously affected by what S.L.A. Marshall called the "shock in battle." At that critical time. a soldier may lose not only his ability to think rationally but some of his physical abilities as well. For these reasons, every extra pound he has to carry reduces his ability to fight.

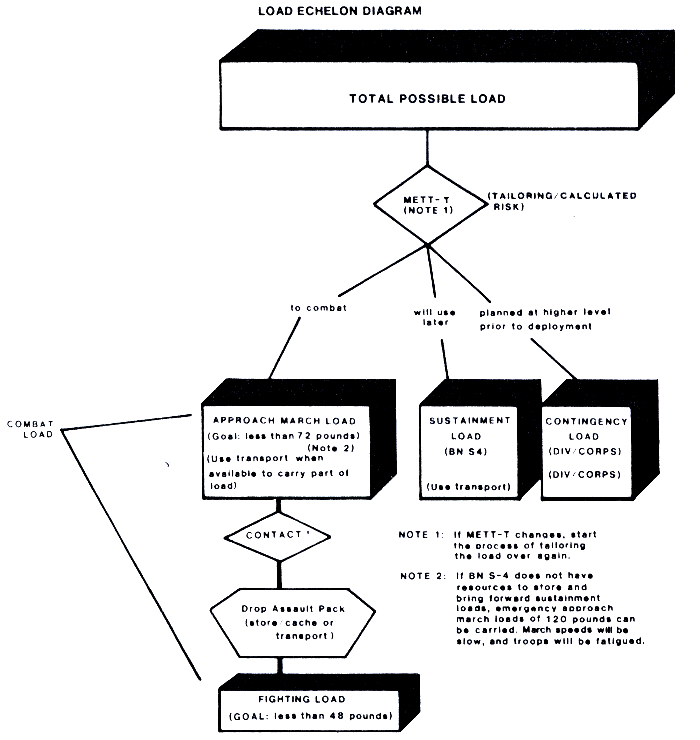

To assist the commander in conducting his risk analysis, ADEA has developed a new concept of dividing the total soldier load, as well as new terminology to support it. The new concept divides the total soldier load into a combat (fighting and approach march) load, a sustainment load. and a contingency load.

The combat load is made up of the minimum mission-essential equipment a commander determines that his soldiers need to accomplish the mission. It is carried by the individual soldiers or on transport that travels with the platoons and companies. There are two levels of combat load: fighting loads, carried in operations where contact with the enemy is expected, and approach march loads, carried when transportation means are not available to carry equipment over and above the fighting loads,

The fighting load is made up of a bayonet, an individual weapon, a small assault pack, a reduced amount of ammunition, clothing and a helmet, and the load-bearing equipment. Soldiers designated for hand-to-hand combat missions or for stealth patrol missions should carry no more than the weapons and ammunition required to accomplish their task, while assaulting troops should carry severely limited loads. Because of cross-loading machinegun ammunition, mortar rounds, antitank weapons, and radio operator's equipment, however, the average assault loads may be well above the desirable limit of 48 pounds. Leaders, therefore, must reconfigure the fighting loads so that any excess can be redistributed to supporting weapon units or shed by assaulting troops before making contact with the enemy, or immediately upon contact.

The approach march load consists of the basic items of clothing, a weapon, a basic load of ammunition, the load-bearing equipment, and a lightly loaded rucksack or poncho roll. On prolonged operations, soldiers must carry enough equipment and munitions to fight and exist until a planned resupply can take place. In offensive operations, soldiers designated as assault troops must also have readily available the items they will need to support the consolidation phase.

The approach march load will vary with the situation and may, on occasion, exceed by a large margin the desirable goal of 72 pounds. Troops can carry rather heavy emergency approach march loads successfully. For instance, in a recent Infantry Board test, soldiers successfully carried 154 pounds over a distance of 20 kilometers. During the Falklands action, British soldiers carried approach march loads of between 120 and 145 pounds.

If a mission demands that soldiers be employed as porters, they can carry loads of up to 100 pounds for several days over distances of 20 kilometers a day. They may even be able to carry loads of up to 150 pounds, but at an increased risk of fatigue and injury. (When they do carry such loads, their contact with the enemy must be avoided, their march speeds must be quite slow, and they must have a chance to rest before entering combat. Rucksacks, assault packs, and other items of the approach march load should be cached or put on the available transport before the soldiers go into battle.)

The sustainment load consists of the equipment required by a commander whose unit must conduct sustained operations. This equipment should be stored by each battalion, normally at the brigade support area (BSA), and brought forward as it is needed. It may include such items as rucksacks (if they were dropped earlier), squad bags, sleeping bags when they are not required for survival, and such spare equipment as platoon early warning systems.

In actual combat, protective items for specific threats, such as armored vests and chemical suits, may be stored in pre-configured unit loads, but in training, this equipment must be stored and carried in the sustainment load, possibly using squad bags. Additionally, items such as Dragon night sights, grappling hooks and ropes, and engineer tools also need to be stockpiled at a point from which the battalion support platoon can push them forward as required.

The contingency load includes all the other items of individual and unit equipment a commander does not deem necessary for a particular operation—extra clothing and personal items and possibly Dragons and TOWs when there is no armor threat. The critical element here is for a commander to determine the make-up of the contingency load and to decide who will be responsible for storing it and for pushing it forward.

The weight an individual soldier carries, then, still depends upon his commander's ability to perform a risk analysis. In the past, planning for all contingencies has made our commanders overly cautious. Certainly no commander wants to be responsible for omitting something that his unit may need on a battlefield. At the same time, he must recognize that carrying additional weight increases fatigue and decreases mobility. In the analysis outlined here, commanders must accept risk on the basis of all available information while still ensuring mission accomplishment. They must learn to see that proper loads are tailored for each mission and must use whatever transportation assets they have to shuttle critical equipment forward to the fighting men.

Research indicates that infantry soldiers must be conditioned for more than running. In fact, most infantryrnen in combat will do little running, but must be able to perform high levels of such anaerobic activity as sprinting, jumping, climbing, and low crawling once they make contact with an enemy unit.

For the infantryman, therefore, the important thing is his ability to sustain a given effort for a period of time, and his march speeds and loads must be so set that he will go into battle with a good reserve of anaerobic capability and energy with which to fight.

Accordingly, road marches with the proper loads must be incorporated into a unit's physical fitness program to improve the soldiers' load-bearing capacity under combat conditions. A train-up and sustainment program should incorporate several types of routines.

The train-up portion of the program might consist of four one-hour daily workouts and up to a day per week for road marching.

Two of the four workouts should be aerobic and should include such activities as exercising to music, circuits, intervals, relays, short (one hour) speed marches with loads, aquatics, bench stepping, target heart rate (THR) training, and unit runs.

The other two workouts should be for muscular strength and endurance to emphasize the upper body. These should include free weight and machine training, obstacle and confidence courses, partner resistance exercises, pushups, situps, and pullup improvements

The road marches should be progressive in nature, with the distances and times increasing until the established goal is reached. These marches can be combined with tactical exercises. and load bearing should be integrated into all training to the maximum extent possible.

The sustainment (and improvement) part of the program is based upon the seven physical training principles outlined in FM 21-20: Regularity, progression, overload, variety, balance, recovery, and specificity.

A full-length article detailing multiple approaches to physical training for light infantry units will appear in a future issue of INFANTRY.

Although technology is providing the infantryman with the tools he needs to fight 24 hours a day in any environment, it will not substantially reduce a soldier's load in the near future. In fact, as in the past, new items may add weight to an already overburdened fighting man.

We must do everything we can to reduce the soldier's load, and we must make sure he is in the best possible physical condition to carry the maximum loads that he can reasonably anticipate carrying in a combat situation.

Major Richard J. Vogel is assigned to the Light Infantry Task Force at the Infantry School. He was S-3 of the 2d Battalion, 9th Infantry, 7th Infantry Division (Light) during its conversion and training for light Infantry. He represented the Infantry School during all light infantry brigade and division certification events

Major James E. Wright is Chief of the Exercise Science Branch at the Soldier Physical Fitness School He previously commanded a medical company in the 2d Armored Division. He has represented the Soldier Support Center to ADEA during the Lighten-the-Load study.

Lieutenant Colonel George Curtis, British Army, has served in Germany, Malta, Cyprus, Norway, West Indies, and Northern Ireland. He is presently the United Kingdom's Special Project Officer on a three-year tour of duty with ADEA at Fort Lewis. With special emphasis on tightening the soldier's load.

- The O'Leary Collection; Medals of The Royal Canadian Regiment.

- Researching Canadian Soldiers of the First World War

- Researching The Royal Canadian Regiment

- The RCR in the First World War

- Badges of The RCR

- The Senior Subaltern

- The Minute Book (blog)

- Rogue Papers

- Tactical Primers

- The Regimental Library

- Battle Honours

- Perpetuation of the CEF

- A Miscellany

- Quotes

- The Frontenac Times

- Site Map

QUICK LINKS

- The Service Kit of the Infantry Soldier (1901)

- The Load Carried by the Soldier (1921)

- The Equipment of the Infantry Soldier In the Light of War Experience (1923)

- The Mobility of One Man (1949)

- Keep The Doughboy Lightly Loaded (1950)

- The Soldier's Load (1955)

- The Accoutrements of the British Infantryman, 1640 To 1940

- A Soldier's Load (1987)

- The Soldier's Load; Planning Smart (1990)

- Soldier Load; When Technology Fails (1987)

- Load Carrying Ability (1990)

- Roadmarching and Performance (1990)

Soldier's Load posts on The Minute Book (blog)

- Soldiers Load (Canadian Militia, 1870)

- The Soldier's Load — The RCR at Vimy Ridge

- FSPB 1914 — Dismounted Soldiers

- Germany 1900-1914

- The Lewis Gun Section (1925)

- Platoon Weapons and Ammunition (1942)

- A historic problem

- The Soldier's Load (1871)

- A Soldier's Load

- The Infantry Platoon; 1942

- Dress and Equipment (1918)

- Soldier's Load; North Africa

- The Soldier's Load; Vietnam

- Factors Causing Soldiers' Overload

- The Soldiers Load; Australia

- The Soldier's Load in Vietnam

- Soldiers' Load — US Army — 1916

- Burden Put on Doughboy

- Sending Men to Death by Overloading

- To Test New Equipment (US Army, 1911)

- Exhaustible Infantry

- What a Soldier Carries

- The Burden the Soldier Boy Carries (1918)

- Japanese Soldier's Load (1910)

- Heaviest Laden Pack Animal in American Army

- Soldier's Kit in South Africa

- [US] Army Tries to Reduce Pack Weight (1963)

- The Soldier's Kit (1932)

- With a 70-Pound Pack (US Army, 1925)

- The Soldier's Load, Canadian Militia (1868)

- Commando Arms and Equipment