His Food and Drink (India, 1859)

Topic: Army Rations

His Food and Drink (India, 1859)

The British Soldier in India, Fred. J. Mouat, M.D., F.R.C.S., Surgeon, H.M.'s Bengal Army, 1859

Fighting needs a full stomach, and the training in peace should always be subservient to the purposes of war, as mentioned above.

Most Europeans in the tropics, in easy circumstances, consume more animal food and stimulant beverages than is good for them. The soldier in particular, except in the field, eats too much meat, drinks more of strong liquors than his system can dispose of with impunity, and takes too little exercise to ward off the effects of his stimulant dietary. The result is that he attains the condition of a Strasburg goose, of which disease and death are the penalty.

Mr. Macnamara in India, and Mr. Gant in England, have shown that the results of the over-feeding of men and cattle are nearly identical. The excess of carbon is not consumed, and being deposited in the form of fat in the liver, kidneys, heart, and muscular tissue, proves rapidly destructive.

In 1853 the rations of the European soldiery in India were fixed at:—

- Bread, 1 pound

- Meat, 1 pound

- Vegetables, 1 pound

- Rice, 4 ounces

- Sugar, 2 1/2 ounces

- Coffee, 1 3/7 ounces

- Or Tea, 0 5/7 ounces

- Salt, 1 ounce

- Firewood, 3 pounds.

The meat is usually beef. Mutton is given twice a week when procurable, and to it the soldier himself adds bazaar pork.

The daily allowance of food thus consumed is more than double the amount issued in the Royal Navy, where the greater part of the life of the individual is spent in the open air, and where he is constantly compelled to undergo an amount of physical exertion unknown to the soldier, except in war.

It would prove much more injurious than it does at present, if the quality were equal to the quantity.

The following, according to Mr. Macnamara, was the ordinary routine life of a soldier of the 1st Bengal Fusiliers at Dinapore:—

"After sleeping through the night in the very hot close air of the barracks, he rises at gun-fire and goes to parade, after which he employs himself in cleaning his accoutrements till breakfast time—8 o'clock. This meal over, he lies down and sleeps till dinner time, and after dinner he generally retires to his bed again, and sleeps more or less till 5 o'clock, the temperature of the barrack being frequently as high as 104° F. at that period of the day. About 5 o'clock he has to prepare himself for parade ; this over, he saunters about till 9 1/2, and then turns in for the night."

To discuss the nature of the nutritive principles contained in food, the due balance between the carboniferous and nitrogenous elements, or any other of the mysteries of dietetics which science is gradually unfolding, is foreign to my purpose.

Those interested in the matter, in its relations to troops,will find much very valuable information regarding it in the report of Mr. Sidney Herbert's Commission, and in the paper of Dr. Chevers.

It is sufficient for my purpose to state that the quantity of meat in the hot weather and rains should be diminished, and that of vegetables increased. The latter can, at all times and seasons, within the cost of the existing dietary, be accomplished with the aid of the desiccated and compressed vegetables now produced and exported in large quantities. The best and most wholesome of them is the dried potato. In the winter the regimental garden could and should furnish all that is needed.

Pork, unless educated in a regimental farm, or better brought up than in the bazaar, should be absolutely prohibited. Fish, in the vicinity of the large rivers, and on the sea-coast, might occasionally, with benefit, be substituted for meat, especially in the hot season.

But, above all, it should be well and properly cooked by the men themselves. The practicability of military cooking was established by the late Monsieur Soyer, as recorded in his culinary campaign. It was popular among the men in the Crimea, and would become so everywhere, if proper attention were paid to it.

Mr. Gubbins, in his graphic account of the siege of Lucknow, mentions incidentally, that when the cook boys levanted, the men of the 32nd had to cook for themselves. They were awkward at first, but soon acquired the requisite skill, and were well satisfied with their performances.

The idleness of the barrack-room, and the necessity of furnishing more occupation for the soldiers in garrison, are alone sufficient reasons for compelling them to cook for themselves in time of peace.

The necessity in the field is still greater, as cooks and followers of all kinds are multiplied to a most injurious extent in India, and are, besides, liable to make themselves scarce when most wanted.

A beginning in the right direction has been made in the Medical Staff Corps, in which professional cooks are regularly entertained. One or two enlisted in every regiment, would soon leaven the mass.

The baking of the bread, grinding of the wheat, and the whole preparation of the food of the soldier for consumption, should, as far as possible, be performed in the barracks and by the soldiers themselves. The more independent they are made, and the more intimate their acquaintance with supplying their own wants, the better for them in every point of view. There is no real difficulty in the matter, and the present helplessness and idleness of the soldiery cannot cease too soon for their morals and their manners, their health and their happiness.

There is scarcely a corps without butchers, bakers, tailors, blacksmiths, shoemakers, bricklayers, gardeners, and most other varieties of handicraftsmen, whose knowledge might and ought to be turned to good use. For those regiments in which they are not to be found, they should be specially recruited.

The subject of the soldier's dietary is, in truth, one of the most important matters connected with his well-being and efficiency. It should never, in any circumstances, be subject to his own control, or be liable to fluctuation on account of deductions from his pay, or from the dear or cheap state of the market near which he may be quartered.

In fact, as stated in the terse and clear language of Dr. Balfour's report:—

"That course should be habitually adopted in peace, which will best satisfy the requirements of a careful administration of the public finances, and be the most applicable to a state of war whenever war may break out.

"An army is maintained in peace with a view to the contingency of war, and it should be so organised as to be capable of expansion with the least possible change of method and system on the part of those who administer it. The mass of mankind do nothing well which they have not done long; and every change unnecessarily made at the commencement of war, when such disturbing influences are unavoidable, is the addition of unnecessary error and confusion.

"It appears to us, therefore, that all the arguments for a fixed stoppage and full ration in time of war apply also to a time of peace. In both cases it is the duty and interest of the Government to see that the soldier is provided with such a ration as will keep him in health and efficiency."

The Committee accordingly recommended one uniform rate of stoppage at home and abroad for the entire ration, the Government supplying the whole.

Fighting needs a full stomach, and the training in peace should always be subservient to the purposes of war, as mentioned above.

The diet of the tropics will necessarily differ from that of the Antarctic regions; that of the plains from the stations in the hills. The determination of the local difference should be left to the experienced medical officers in each, care being taken in all cases that the highest attainable standard of health and efficiency is maintained.

The question of strong waters is more difficult to determine. In this desirable direction much has been done by the judicious regulation of canteens; by the sale in them of sound, wholesome, malt liquors at reasonable rates; by the increasing taste for tea and coffee; and by the example of the officers, whose own habits have changed with the general change of society in this respect.

Temperance Societies are opposed to military discipline, and are of little efficacy. The real means of weaning the soldier from his present pernicious indulgence in the fatal habit that kills more than the sun, marsh, and sword combined, is to improve his moral and social condition, to hold out greater inducements to good men to enlist, to encourage marriage and the amenities of an honest man's home in the soldier's barrack, to introduce the practice of industrial occupations, and to furnish the means of such amusements as invigorate the frame without inducing ennui. These are bowls, quoits, cricket, rackets, gymnastics, swimming, and such other out-door amusements as healthy men never tire of, and drunken sots seldom indulge in.

That the men themselves readily take to such pastimes, who can doubt who has been acquainted with them in their own homes, before every moral feeling and healthful excitement has been blunted and blighted by the idleness and vice of the barrack-room as it now is? The practice of issuing rations of rum to young recruits should at once cease. Many a fine lad has been ruined by it.

To pursue this topic further is unnecessary. The magnitude and corroding influence of the vice are self-evident. The statistics of army disease record, with unerring accuracy, its general and fatal prevalence. It has literally realized the prophecy of Milton, that

"Intemperance on the earth shall bring Diseases dire, of which a monstrous crew Before thee shall appear."

Of the efficacy, in due time, of the remedial measures suggested above, we entertain not the smallest doubt. The good work has, indeed, already begun, but like all other social changes, to be permanent in its results, its growth must be gradual.

Posted by regimentalrogue

at 12:01 AM EST

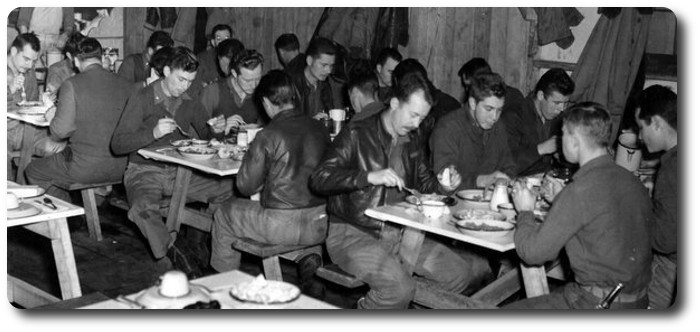

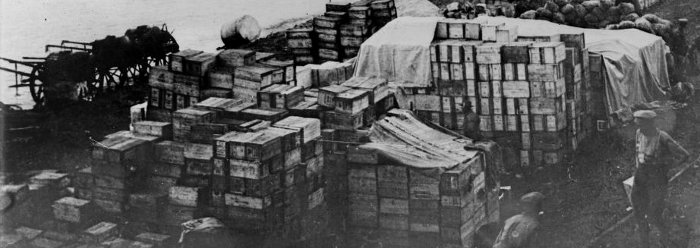

Whatever the Australian troops may be called upon to undergo in the nature of hard rations in the field, when they are in the depot and standing camps in Australia they have abundant and excellent food. Their ration is more liberal than that of almost any army in the fighting fields today, or amongst the forces of the mobilised central powers. Bully beef and biscuits, jam, biscuits and bully beef, jam, alternated, disguised with a dash of vegetables, was the ration at Anzac. It was a good ration, too, for any army fighting and moving every day, and with an abundant water supply available. But it was monotonous diet for such a campaign as Gallipoli, and unhealthy as well when the water supply was so strictly limited. Casting aside the condiments, and the little extras that came to hand, this was the staple food of the Australian army in the field. Compare it with the 1 ¼ lb. bread (or 1 lb. biscuit), and 1 1/2 lb. meat (or 1 lb. fresh or salt fish), 1 lb. potatoes and 8 oz. mixed vegetables that the troops at the camps throughout the Commonwealth have as the basis of their daily meals. Flour, rice and curry powder are a weekly ration, which helps the cooks to give variety to a breakfast, lunch or dinner. An army fights on its stomach; it builds up reserve in physique, muscle and toughened sinew by long hours of drilling, marching, exposure to the elements; it lives and prospers on the rations that are provided after a day of vigorous training and campaigning.

Whatever the Australian troops may be called upon to undergo in the nature of hard rations in the field, when they are in the depot and standing camps in Australia they have abundant and excellent food. Their ration is more liberal than that of almost any army in the fighting fields today, or amongst the forces of the mobilised central powers. Bully beef and biscuits, jam, biscuits and bully beef, jam, alternated, disguised with a dash of vegetables, was the ration at Anzac. It was a good ration, too, for any army fighting and moving every day, and with an abundant water supply available. But it was monotonous diet for such a campaign as Gallipoli, and unhealthy as well when the water supply was so strictly limited. Casting aside the condiments, and the little extras that came to hand, this was the staple food of the Australian army in the field. Compare it with the 1 ¼ lb. bread (or 1 lb. biscuit), and 1 1/2 lb. meat (or 1 lb. fresh or salt fish), 1 lb. potatoes and 8 oz. mixed vegetables that the troops at the camps throughout the Commonwealth have as the basis of their daily meals. Flour, rice and curry powder are a weekly ration, which helps the cooks to give variety to a breakfast, lunch or dinner. An army fights on its stomach; it builds up reserve in physique, muscle and toughened sinew by long hours of drilling, marching, exposure to the elements; it lives and prospers on the rations that are provided after a day of vigorous training and campaigning.

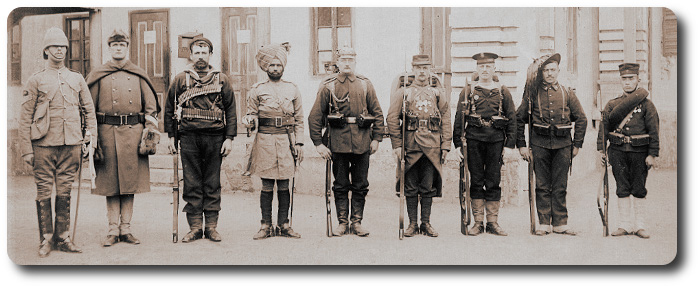

Color Sergeant Thompson of 40 Gwynne Avenue, [Toronto], now with the Second Battalion, Royal Canadian Regiment, in South Africa, writes home:

Color Sergeant Thompson of 40 Gwynne Avenue, [Toronto], now with the Second Battalion, Royal Canadian Regiment, in South Africa, writes home:

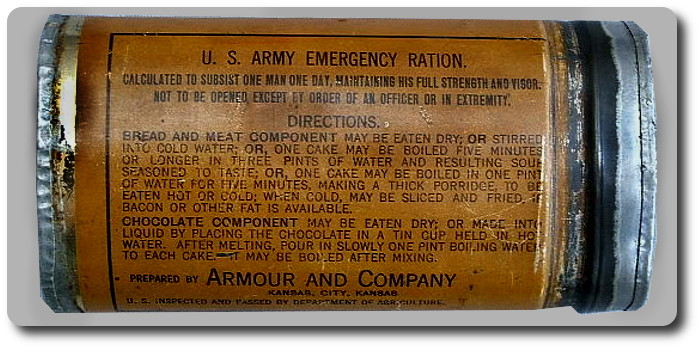

Frozen meat at present constitutes 60 per cent of the total meat issued to the British army. The remainder is made up of preserved meat of several varieties. The most familiar form is the well-known "bully beef," which is corned beef packed in small oblong tins, each containing 12 ounces. Some units cook their bully beef, other prefer it just as it comes from the tin. In comprised the principal article of diet for the army at Gallipoli.

Frozen meat at present constitutes 60 per cent of the total meat issued to the British army. The remainder is made up of preserved meat of several varieties. The most familiar form is the well-known "bully beef," which is corned beef packed in small oblong tins, each containing 12 ounces. Some units cook their bully beef, other prefer it just as it comes from the tin. In comprised the principal article of diet for the army at Gallipoli.

The Age, Melbourne, Australia, 17 June 1960

The Age, Melbourne, Australia, 17 June 1960