Training a Citizen Army (1939)

Topic: Drill and Training

Training a Citizen Army (1939)

Recruit to Finished Soldier

The Militia Learns Its Job

The Sydney Morning Herald, Sydney, Australia, 1 November 1939

By a Special Correspondent

The Australian citizen soldier, who is now being trained in the military art in a score of camps throughout the Commonwealth, is undergoing a type of training which will produce materially different results from those which characterise the French, British and German armies which face each other in Europe.

The military training which is being accorded to the 80,000 members of the Militia, and the 20,000 men of the Second A.I.F., is not an ephemeral product of haphazard thinking, hastily applied to meet some nebulous or unexpected military situation. Australia's defence authorities, and the British Army experts who have advised them for more than 30 years, have tried to shape the training to meet specific Australian needs and problems, the chief of which is the problem of resisting an invasion from the sea.

Australia is an island continent. It is, of course, impossible to invade out shores in the manner in which the Germans invaded France in 1914, and Poland in 1939—by mobilising 1,000,000 men and vast quantities of artillery behind a land frontier, and suddenly giving them the order to march. No enemy forces can occupy Australia without first effecting a landing in boats, preferably at a number of points simultaneously, in order to divide the defenders. The prime need of the defending forces, taking naval action out of account, is, therefore, to meet the attacks wherever they may occur, and the availability of highly mobile reserves to reinforce the defenders wherever the pressure is greatest.

The Australian soldier need not expect to face an enemy massed in overwhelming numbers, since the size of an invading army would be strictly limited by the number of transports which could be assembled, nor would he expect to deal with anything like the concentration of heavy artillery and mechanised equipment employed in military operations in Europe. His superiority over such an enemy would rest with his prepared position, his power of concealment, his land (instead of sea) communications, and his intimate familiarity with the terrain. In all of these respects the enemy would be at a serious disadvantage.

Training to Timetable

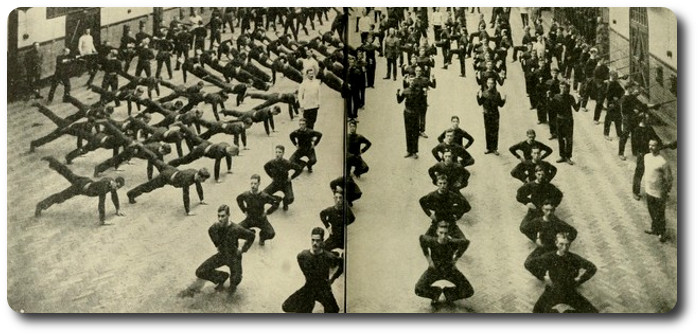

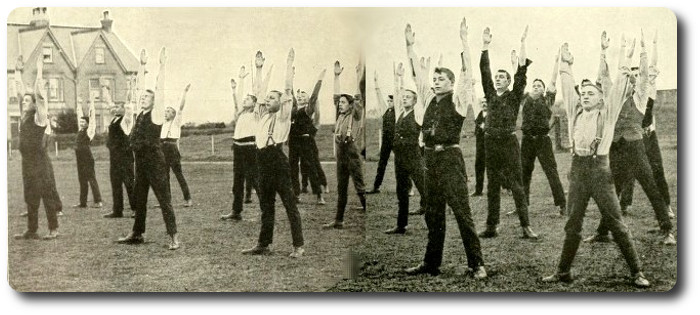

It is with such factors as these in mind, that the Australian army training system has been devised. It aims at providing the militiaman with a complete all-round training system has been devised. It aims at providing the militiaman with a complete all-round training in four months, a tall order, it is true, but one from which there can be no escape in the immediate future.

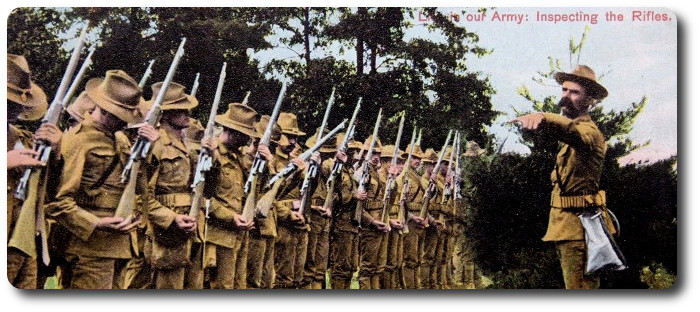

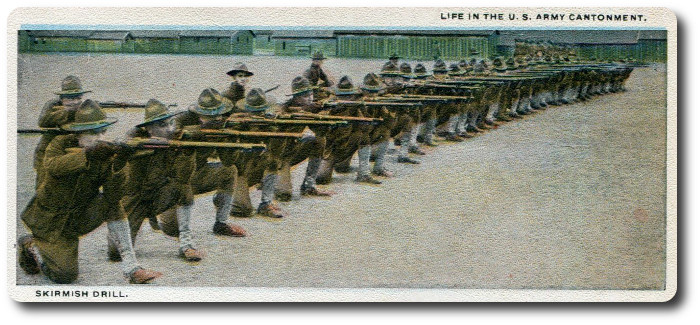

The work is divided into sections, and it is performed to a time schedule. Thus the first month is devoted to elementary instruction in arms, musketry, close order dill, and a general shaking down to camp routine. The only team work accomplished in this month is restricted to company drill. In the second month, more complicated tasks are undertaken. The soldier may be introduced to bayonet practice, musketry instruction, moves from the short range to the longer rifle range, and from company drill the men graduate to battalion drill, undertaking field exercises on a miniature scale. At the same time all the work done in the first month is revised.

When the third month is reached the soldier moves on to more advanced work. In this period, brigade field exercises may have a place. Route marches may be undertaken now that muscles have become hardened, instructions may be given in trench digging and wiring, and simple tactical exercises may be practised under active service conditions. As before, there is a good deal of repetition of the second month's work on the principle that practice makes perfect.

In the fourth month, the earlier instruction is supplemented by divisional field exercises. The soldier at last rehearses complicated battle manoeuvres on a scale comparable with what might be expected in war. The route marches are now carried out in full service kit, there are exercises in which co-operation is lent by the Navy, artillery and Air Force, and the men learn the difference between manoeuvres carried out by day and under cover of night.

Field Manoeuvres

By now the soldier has made the acquaintance of the entire training manual, he is physically fit and seasoned, he understands the meaning of discipline, and he appreciates the value of individual resource. He knows what is expected of him, and if lacks the complete efficiency and versatility of the European soldier, trained to arms over a period of years, rather than months, the deficiency can be repaired by a few months of intensive training, if the need should arise. Or at any rate by an additional period of training in the second year.

The more advanced stage of militia training includes exercises for the repulse of beach landings. As a result of careful staff work, these exercises have attained a high degree of efficiency. They are usually carried out at night and involve the close co-operation of artillery, machine-guns, reconnaissance planes, Signal Corps, transport, and commissariat department.

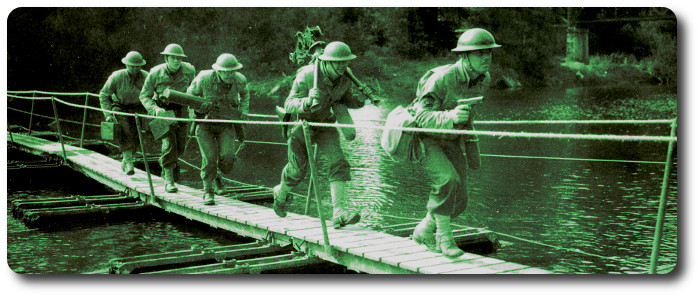

Another exercise which is now a regular part of militia training involved the crossing of unbridged rivers at night. It is an infantry as distinct from an engineers' operation. The instrument used for effecting the crossing is a kapok bridge or pontoon, which is assembled a short distance from the river bank at about 3 a.m. the floats, carried up the communication lines by the men, are lashed together with lengths of decking, so that long before dawn the finished bridge lies on the bank ready for launching. The operation is carried out in complete darkness and silence to conceal the manoeuvre from the enemy.

At zero hour the bridge is launched and the infantry crosses the river with its machine-guns, taking the enemy by surprise. Rivers 80 ft wide have been crossed successfully in this way, the troops being equipped with full war kit, including gas masks. As a substitute for the kapok bridge recourse is sometimes made to collapsible pontoons, each holding eight men.

Practising Retreat

It is proposed this year to devote considerable attention to the operations involved in tactical withdrawal. This form of field exercise, possibly the most difficult of all, has been neglected in Australia, except on paper, although it is a necessary part of army training in every other country in the world. With the extension of camp periods from 18 days to four months, it will now be possible to devote some useful time to this important manoeuvre.

The practice of tactical withdrawal, or retreat, is difficult, not only because its component operations are in reverse movement, but also because its success depends on even more careful timing than is involved in an offensive action. The essence of the plan is to withdraw the defending force at such time, at such speed, and with such measure of concealment that the enemy is not aware of the manoeuvre until his forces have moved forward to the assault. It has its maximum effect when, at the moment the enemy has gathered himself to advance, he finds that the defenders have vanished, confronting him with the fresh and laborious task of locating them and preparing other plans for attacking new and unmapped positions.

Such a movement imposes considerable strain upon the retreating forces, and calls for a high degree of discipline and resource. Men who are unfamiliar with the manoeuvre, and who may be left behind to act as a covering force, with orders to increase their rate of fire to deceive the enemy, are apt to fire so so rapidly that the curiosity of the enemy is aroused and the whole stratagem is defeated. The withdrawal will be jeopardised, too, if one battalion delays its retirement, necessitating a modification of the manoeuvre while the unit is relieved and extricated.

The new camp training schedule is designed to give militiamen, and especially officers and non-commissioned officers, a clear understanding of the intricate operations involved in withdrawal and, at the same time, fill in a hitherto conspicuous gap in military practice in Australia.

School for Officers

The improved efficiency which may be expected from officers and N.C.O.'s as a result of the extension of the camp training period is, indeed, one of the hopeful aspects of the new training scheme. For the task is not merely to train 100,000 clerks, labourers, farmers, miners, professional men, and so on, and to become good soldiers, but to increase the competency of the young militia officers and N.C.O.'s who will be the Army leaders and instructors of to-morrow.

Great importance, therefore, attaches to the officers' training school which has ben established at Studley Park, Camden, under the revised Army system. Here the officers attached to militia units in the Eastern command, including subalterns, warrant officers, and senior non-commissioned officers, are receiving advanced training in arms and military tactics. Instruction in the three wings of the school, namely, infantry, artillery, and cavalry, is given by Staff Corps officers, assisted by sergeant-majors drawn from the Australian Instructional Corps. Each course of training lasts for two weeks, and the school is so busy that it is open continuously, one batch of officers going in as the other goes out.

The Studley Park establishment is an extremely valuable adjunct to the training scheme. It will quickly improve the capabilities of militia officers and inspire renewed confidence and enthusiasm in the ranks of the men whim they will lead.

Posted by regimentalrogue

at 12:01 AM EDT

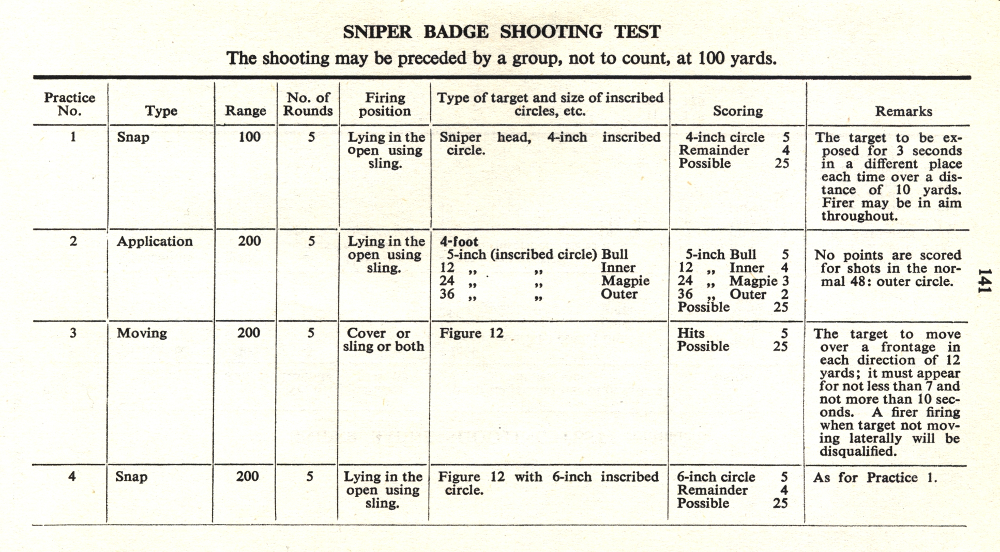

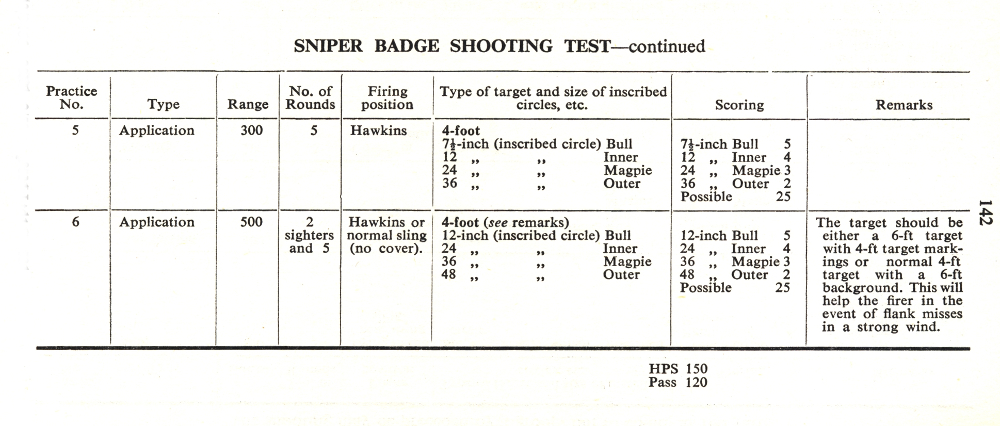

Sniper Badge Shooting Test (1951)

Sniper Badge Shooting Test (1951)

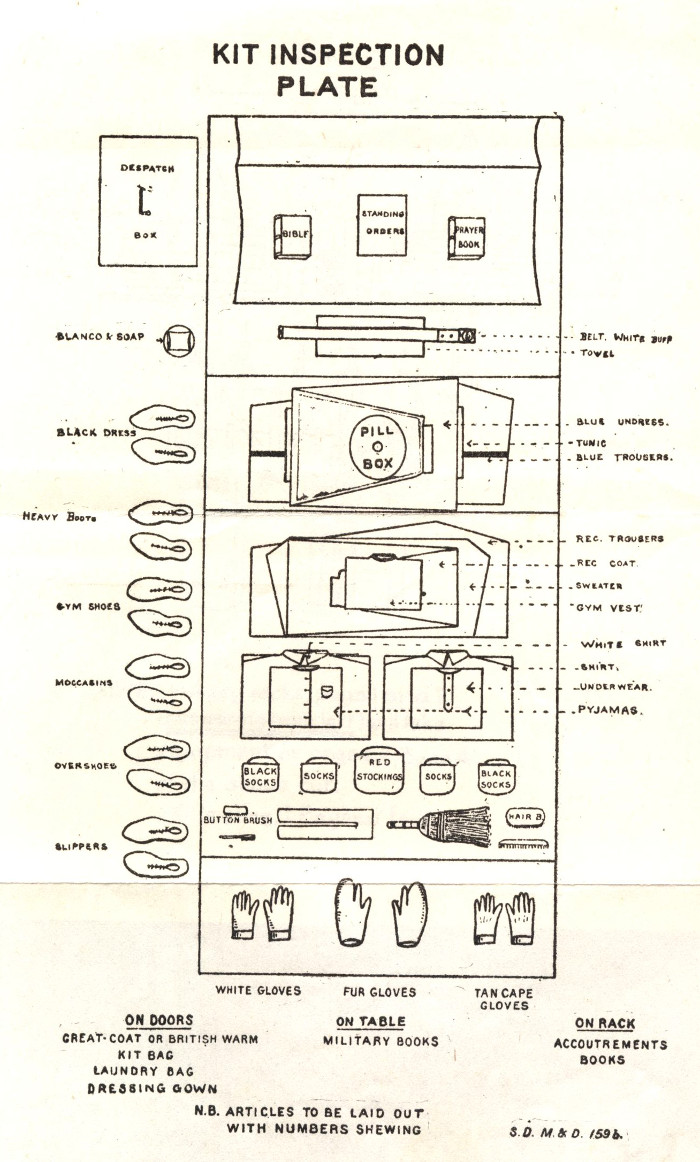

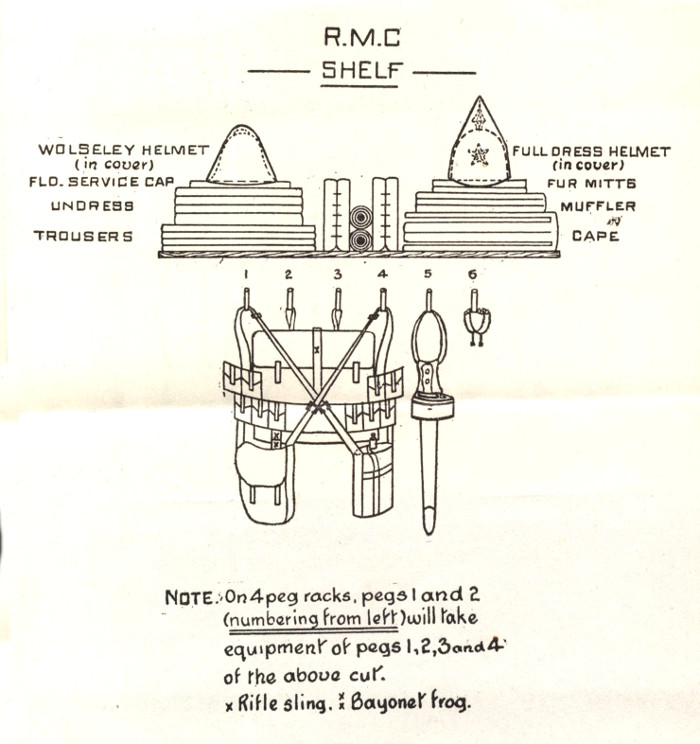

Each soldier in a modern army carries with him sufficient food, clothing, shelter, fighting arms and ammunition to take care of himself for a short period in case he should be separated from his company. The total weight of his load, in addition to the clothes he wears, is 50 to 70 pounds. The number of articles is surprisingly large. They are so devised, however, that by ingenious methods of packing and adjusting they can all be carried with the least possible effort.

Each soldier in a modern army carries with him sufficient food, clothing, shelter, fighting arms and ammunition to take care of himself for a short period in case he should be separated from his company. The total weight of his load, in addition to the clothes he wears, is 50 to 70 pounds. The number of articles is surprisingly large. They are so devised, however, that by ingenious methods of packing and adjusting they can all be carried with the least possible effort.