Officer's Right to Wear His Uniform

Topic: Discipline

Officer's Right to Wear His Uniform

Case Against Major ("Foghorn") MacDonald Opened in Police Court

Disputed Regulation

Defence Contended That Major Could Not Be Discharged During Duration of War

The Montreal Gazette, 14 September 1918

Questions as to the legality of the act of the Adjutant-General of Canada in striking Major Neil Roderick ("Foghorn") MacDonald from the strength of the active list of the Canadian Expeditionary Forces and transferring him to the reserve of officers were set by Mr. W.K. McKeown, K.C., counsel for the defence, when the trial charging Major MacDonald with wearing a uniform without permission when off duty opened in the Police Court before Judge Leet yesterday.

Mr. McKeown, throughout the course of the proceedings, declared that it was the intention of the defence to prove that the act was not in conformity with the agreement entered into between the King and major MacDonald, when the latter enlisted as a private in the Canadian Army. Another serious question raised by the attorney for the defence was whether the Canadian Expeditionary Force is part of the Canadian Militia and governed by the King's regulations for the Canadian Militia, or whether it was part of the British army and governed by the King's regulations for the Imperial army. The legal points were the subject of much debate among the lawyers and Lieut.-Col. Hill. G.S.O., who was the star witness for the for the prosecution.

When the case was opened Mr. M.L. Gosselin, K.C., acting for the prosecution, declared that Major MacDonald had been struck off the strength of the Canadian Expeditionary Force on December 14, 1917 and that by routine order of march 18, 1918, Major MacDonald was transferred to the reserve of officers. He was off duty since December 14, and had been warned to take off his uniform, which he had been wearing in public. Mr. McKeown, however, contended that Major MacDonald had enlisted for the duration of the war and six months after it had concluded if necessary, and had made a contract with the King. He went overseas as a private and rose to the rank of major. Application was then made for his transfer to the Forestry Corps, and after serving for three years in France he was successful, last fall, in securing a furlough for three months. While in Canada, he was struck off the strength without his request. The defence, therefore, contended that a man could only be struck off the strength for three reasons, viz., death, discharge, and the stopping of pay.

Liable for Service

Judge Leet then asked Mr. Gosselin if Major MacDonald could be called upon to render military services while a member of the reserve of officers, and Mr. Gosselin replied in the affirmative, stating that any man is liable to be called up. In the meantime, however, he is not serving. "If they had needed Major MacDonald's services," said Mr. Gosselin, "they would have kept him on active service. This man has tendered his resignation."

Judge Leet—"Has it been accepted?"

Mr. McKeown—"No. My Lord, that's what we contend."

Lieut.-Col. Hill was then called to the stand to give evidence. He explained that Major MacDonald had no right to wear the King's uniform after December 14, when he was struck off the strength of the C.E.F., and his pay stopped. When asked who issued the order regarding Major MacDonald's discharge, Col. Hill said that it came from the Adjutant-General at headquarters.

At this point the question whether the C.E.F. was part of the Canadian Militia or the British army was raised. Col. Hill declared emphatically that the C.E.F. was part of the Canadian Militia, while Mr. McKeown was of the opinion that it was part of the British army, and Judge Leet seemed to think along the same lines as the lawyer.

"While in England," said the colonel, "they come under the direct control and supervision of the Overseas Minister of Militia. When in France they come under the British army."

Col. Hill, in continuing his evidence, said that Major MacDonald had received forms from the Adjutant-General asking him to fill them in if he desired to be placed on the Reserve of Officers. Instead of that Major MacDonald said he wished to return to the infantry.

Mr. Gosselin—"Did you see Major MacDonald last February?"—"In February or early in March."

"In connection with the uniform?"—"Yes. It was reported to me that this officer was appearing in public in uniform. I had written to him on February 28 about this matter, and had advised him not to wear it again. After he received the letter he came to see me. He gave me to understand that he was shortly to get his civilian clothes, and as soon as they were ready he would discontinue wearing his uniform.

Serve During War

Mr. Mckeown—By the declaration made by officers do they engage to serve during the war similar to the men?—I think so.

Do you know of any document signed by Major MacDonald which would modify those attestation papers?—he was notified that he was struck off the strength and was transferred to the reserve of officers. He acknowledged this and thereby accepted it.

Do you refer to the document regarding the transfer in which he stated that he wished to be transferred to the infantry?—Yes.

You referred to this as an application of transfer to the reserve. Is it not true that this document shows nothing of the kind, that there is nothing said in it indicating that Major MacDonald thereby applied to be transferred to the reserve? Is there any mention of the reserve in this document?—Not on the face of it.

Have you any other documents to indicate whereby Major MacDonald in any way modified the terms of the original attestation in December, 1914?—No, there is no record. There is a record of his having signed a document promoting him for commissioned rank.

You have stated, Col. Hill, that Major MacDonald was struck off the the strength on December 14, 1917, what was the procedure by which major MacDonald was struck off the strength at that time?—A letter from the Adjutant-General at headquarters to the O.C. of Military District No. 4 informing him that in accordance with his request Major MacDonald had been struck off the strength.

How long have you been with the Militia?—Twenty-two years.

Are you conversant with the King's regulations and orders which govern the Canadian Militia, which govern the British army?—We have the King's regulations for the Canadian Militia and there are also the King's regulations for the Imperials.

Which apply to members of the Canadian Militia?—Both.

Which has the precedence?—In Canada, the Canadian, overseas the Imperial.

From Adjutant-General

Are you familiar with these two sets?—Fairly well.

Can you indicate to the court the authority for the letter dated Ottawa, December 28, 1917, purporting to report that Major MacDonald had been struck off the strength from December 14, 1917?—That's a letter from the Adjutant-General or one of his deputies. That letter was written under the authority given the Adjutant-General,

Which set?—General order No. 1 of 1905, under the duties of the Adjutant-General.

Is there anything in the King's regulations and orders for the Canadian Militia giving authority for the letter, apart from section 11, paragraph c.?—Undoubtedly, I don't happen to know it.

I mean is there any other order which will justify this letter?—Not that I know of.

Can you indicate anything in the King's regulations and orders authorizing the striking off strength of officers and their transfer to the reserve list?—Paragraph 26.

Are there any other provisions in the King's regulations and orders dealing with the transfer of officers to the reserve?—Not that I know of.

According to you, under which set of these regulations does Major MacDonald fall?—The regulations for the Canadian Militia.

Is it not a fact that the officers are struck off the strength only in virtue of district orders, and not by letters?—Not necessarily. A letter from the Adjutant-General is sufficient authority.

Now is there any cause assigned anywhere for the action in striking Major MacDonald off the strength?—yes.

The witness then produced a letter from the Adjutant-General to major-General Wilson, dated November 14, 1917, stating that Major MacDonald's leave expired on December 13, 1917, and that a communication had been received from overseas saying his services would be more valuable in Canada than overseas. The letter informing the Adjutant-General of this was written by Major Moorhead, director-general of timber operations.

In continuing the cross-examination, Col. Hill said that Major MacDonald's record was a clean one, and that he had risen from the ranks to a high post in the army.

Mr. McKeown told Judge Leet that there was absolutely no power or authority by which the militia could discharge Major MacDonald from the active force and transfer him to the reserve list.

Col. Hill also admitted that the transfer to the reserve did not change Major MacDonald's status, and that being struck off the strength did not affect his standing as an officer. It merely meant that he was not a member of the active force.

Capt. J.S. Livingstone, provost-marshal, was the second and last witness to be called by the prosecution.

Did you see him in the month of August in connection with the wearing of his uniform?—I did.

What was your object in speaking to him?—To have him take it off.

The witness declared that Major MacDonald had informed Col. Piche, acting O.C. for Military District No. 4, that he would take off his uniform.

This concluded the evidence, and Judge Leet announced that the case would be adjourned until Thursday morning next, when the defence will be heard.

Charge Against Soldier Dropped

Concerned Major ("Foghorn") MacDonald's Right to Wear Uniform New Order-in-Council Gave Power to Try By Courts Martial, But Major Appeared in Mufti

Montreal Gazette, 20 September 1918

An effective compromise in the case of Major "Foghorn" MacDonald's persistence in wearing his uniform in defiance of orders from the provost marshal and the military authorities to the contrary developed yesterday afternoon in the Police Court, when the defendant appeared for the first time in mufti and Mr. Louis Gosselin, K.C., representing the plaintiff, withdrew the case because the order-in-council under which he had been prosecuting the defendant had been superceded by a new order-in-council lately issued. Mr. W.K. McKeown, K.C., for Major MacDonald indicated that his client abated not one jot or tittle of his claims that he had the right to wear the uniform but had resumed mufti because his understood that it had been the intention to arrest him on the withdrawal of the police court proceedings in order to try the case by court martial under the new order-in-council. It was intimated by Mr. McKeown that the case would next reappear on the floor of the House of Commons.

Mr. Louis Gosselin, K.C., opened the proceedings by saying, "I wish to make a statement regarding the MacDonald case. The authority underlying the prosecution of Major MacDonald for the wearing of his uniform while not actually on active service and without permission was order-in-council, P.C. 17, dated January 4, 1918. Dince this case began the order-in-council 17 has been replaced by order-in-council P.C. 2161. The new order-in-council does not reserve any pending litigation. The authority under which this prosecution was commenced having lapsed, it had become necessary to withdraw this case. Such a case as the present one now finds authority under order-in-council P.C. 2161, which grants recourse either to a court martial under Section 40 of the Army Act or to the Civil Courts.

"I now find that since the adjournment this morning Major MacDonald has discarded his uniform and is now in mufti. This is in compliance with the law which was all we wanted. Under these circumstances, I suppose the case will be dropped.

Mr McKeown's Statement

Mr. W.J. McKeown, K.C., made the following statement on behalf of Major MacDonald:

"On behalf of Major MacDonald I wish to publicly declare that he has had no participation whatever in the move just made by the militia authorities in withdrawing the charge of wearing his uniform as a major without right.

"The proof already of record by the witnesses for the prosecution shows that from the time of his enlistment in September, 1914, to date, there has never been any charge whatever made against Major MacDonald, and that on the contrary his services to his king and country on the battlefields of Flanders earned for him successive promotion from private to the rank of major. After three years' service he applied for an was granted three months furlough and it was while Major MacDonald was here in Canada enjoying a well-earned rest, that the militia authorities took it upon themselves to dispense with his further services.

For Duration of War

"Major MacDonald's contention has always been and still is that in virtue of his attestation papers of September, 1914, and order-council No. 372, his enlistment was for the duration of the war and his status that of an officer of the British army, and that he is in no way subject to the orders of the Militia Department at Ottawa, and in any event, that no authority exists for the action of the adjutant-general taken in December last in striking him off the strength of the C.E.F. or for the routine and district orders of March following purporting to transfer him to the reserve list of C.E.F. officers.

"It having been intimated to Major MacDonald that it is the intention of militia authorities immediately upon the withdrawal of the police court proceedings, to cause his arrest for trial by court martial under an order-in-council dated the 5th of the present month, and not yet published in the Canada Gazette he has, upon advice of counsel decided to return to mufti so that the substantial question of his status and rights may be neither obscured nor jeopardized by a decision of a court martial upon a technical offence involving only the matter of his right to wear his uniform.

"It is, however, the intention of Major MacDonald's friends to pursue what they believe to be his rights in the connection, and to maintain the same by every legal means available and it is quite likely that the current subject will be aired upon continuance of the House of Commons in the next session. There is no objection to the withdrawal of the complaint on the present occasion."

Military Discipline

Judge Leet—"What is the distinction between the old and the new authority?

Mr. Gosselin—"The new authority provides that the man who wears the uniform without right is by that act made subject to military discipline and law and may be dealt with under Section 40 of the Army Act for conduct contrary to discipline. The fact of wearing a uniform subjects a civilian to military discipline for the purposes of that offence only. Under those circumstances I could not proceed but had to take the prosecution under the new order-in-council and that will only permit a trial before court martial. A man wearing the uniform is made subject for that purpose to a court martial. We are not after punishment of any kind but we did desire that the major should comply with orders. The theory of the Militia Department is that he is already discharged. He was requested to take his uniform off and on two occasions he promised. He is in mufti now, and we are satisfied."

Judge Leet—"As the original authority has been superseded, I don't see that there is anything to do but to allow the withdrawal."

Posted by regimentalrogue

at 12:01 AM EDT

Combat Lessons, Number 2, September 1946

Combat Lessons, Number 2, September 1946

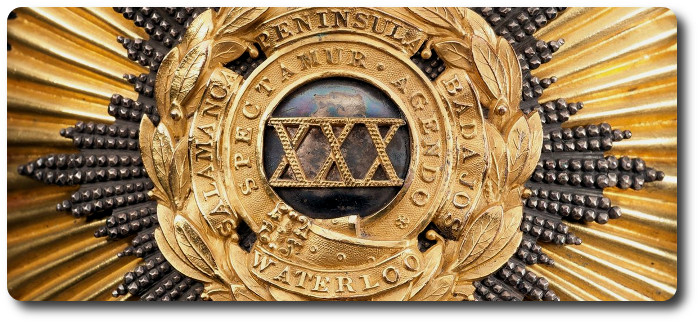

In Toronto there lives a retired colonel of the British army, staunch and loyal, who allowed a private soldier of good character, in the 30th Regiment, to marry his daughter. His regiment, soon after he marriage, was ordered to Montreal, and he took his wife with him, where he deserted both her and the Queen's service, and came across the lines to the protection of the stars and stripes. The colonel indignantly sent for his daughter, and she has continued to live with him, hearing occasionally from her husband, but refusing, or rather permitting her father to do it for her, to go to him as requested. Last week they were suddenly surprised by the appearance of the deserter, who entered the house without ceremony. His wife flew to him and her father at him, the latter arresting him as a deserter from Her majesty's service. In vain did the son-in-law argue and the daughter weepingly plead. With Roman firmness the British colonel insisting upon handing him over to the authorities, assuring him that thus he should treat his son or his brother, had either been a traitor. With an unyielding conviction of duty, the colonel dragged his erring relative to the barracks, and gave him up to the penalties of the law.

In Toronto there lives a retired colonel of the British army, staunch and loyal, who allowed a private soldier of good character, in the 30th Regiment, to marry his daughter. His regiment, soon after he marriage, was ordered to Montreal, and he took his wife with him, where he deserted both her and the Queen's service, and came across the lines to the protection of the stars and stripes. The colonel indignantly sent for his daughter, and she has continued to live with him, hearing occasionally from her husband, but refusing, or rather permitting her father to do it for her, to go to him as requested. Last week they were suddenly surprised by the appearance of the deserter, who entered the house without ceremony. His wife flew to him and her father at him, the latter arresting him as a deserter from Her majesty's service. In vain did the son-in-law argue and the daughter weepingly plead. With Roman firmness the British colonel insisting upon handing him over to the authorities, assuring him that thus he should treat his son or his brother, had either been a traitor. With an unyielding conviction of duty, the colonel dragged his erring relative to the barracks, and gave him up to the penalties of the law.

The average civilian, no matter how brave he might be, has little desire to go into battle. Even though he knows very well that the chances of his being killed or wounded are comparatively small, yet the thought of placing himself in a post of danger face to face with a well trained and courageous enemy is more or less terrifying to him.

The average civilian, no matter how brave he might be, has little desire to go into battle. Even though he knows very well that the chances of his being killed or wounded are comparatively small, yet the thought of placing himself in a post of danger face to face with a well trained and courageous enemy is more or less terrifying to him.

John Roach, aged 34, was indicted for the wilful murder of Daniel Maggs, in the

John Roach, aged 34, was indicted for the wilful murder of Daniel Maggs, in the

His Excellency the Commander in Chief has been pleased to direct that Captain Hanson's Company, No. 1, of the

His Excellency the Commander in Chief has been pleased to direct that Captain Hanson's Company, No. 1, of the

The most heartbreaking part of an officer's or N.C.O.'s work during the period of recruit training is to educate Australians to submit to discipline. It is almost an impossibility to teach a new man to instantly obey and order, and to get him into the soldierly habit of coming to attention when addressing anyone of superior rank, or saluting when passing him in camp or elsewhere. It necessitates a very complex knowledge of the Australian character to account for this peculiarity in the men, and a study of his individuality, descent, and all the influences at work upon the man from infancy to adult life, before an officer may consider himself qualified to handle new recruits, and change their modes of thought.

The most heartbreaking part of an officer's or N.C.O.'s work during the period of recruit training is to educate Australians to submit to discipline. It is almost an impossibility to teach a new man to instantly obey and order, and to get him into the soldierly habit of coming to attention when addressing anyone of superior rank, or saluting when passing him in camp or elsewhere. It necessitates a very complex knowledge of the Australian character to account for this peculiarity in the men, and a study of his individuality, descent, and all the influences at work upon the man from infancy to adult life, before an officer may consider himself qualified to handle new recruits, and change their modes of thought.

The last report of the British "Eye Witness" at the front contained some interesting allusions to certain methods current in the German Army for the purpose of maintaining its cast-iron rigidity and its mechanical, it not its spiritual, efficiency. "The discipline," he writes, "is principally that of fear, the men being in positive terror of their officers, who behave with a kind of studied truculence more befitting slave-drivers than leaders of men … This is borne out by the use of the cat-o'-nine tails, which is well established, one of these instruments having been captured by us near Neuve Chapelle … Such," he continues, "is the fear of the officers and the general mistrust that the men do not even speak to one another of their grievances for fear that their complaints should reach the ears of their seniors. Of the outward forms and restraints of discipline there is no relaxation even in the trenches. When an officer passes the men must spring to attention and must remain with shouldered arms, without moving a muscle, perhaps for a quarter of an hour., while the officer in question is near them. When they are relieved from the trenches every spare moment is devoted to drilling and training. The slightest fault is punished with extreme severity, the offenders often being tied to a tree for hours together."

The last report of the British "Eye Witness" at the front contained some interesting allusions to certain methods current in the German Army for the purpose of maintaining its cast-iron rigidity and its mechanical, it not its spiritual, efficiency. "The discipline," he writes, "is principally that of fear, the men being in positive terror of their officers, who behave with a kind of studied truculence more befitting slave-drivers than leaders of men … This is borne out by the use of the cat-o'-nine tails, which is well established, one of these instruments having been captured by us near Neuve Chapelle … Such," he continues, "is the fear of the officers and the general mistrust that the men do not even speak to one another of their grievances for fear that their complaints should reach the ears of their seniors. Of the outward forms and restraints of discipline there is no relaxation even in the trenches. When an officer passes the men must spring to attention and must remain with shouldered arms, without moving a muscle, perhaps for a quarter of an hour., while the officer in question is near them. When they are relieved from the trenches every spare moment is devoted to drilling and training. The slightest fault is punished with extreme severity, the offenders often being tied to a tree for hours together."