Topic: The Field of Battle

Lessons Learned by the Wehrmacht, Poland (1939)

The German Campaign in Poland (1939), by Robert M. Kennedy, Major, Infantry US Army, April, 1956

Bock expressed the opinion that the old adage "The infantry must wait for the artillery" should be changed to "The artillery may not delay the infantry."

Conclusions; General

The German campaign in Poland in 1939 has been regarded by many as little more than a maneuver for the youthful Wehrmacht. However, the casualty figures and losses in materiel for the period of combat show that the campaign was more than an exercise with live ammunition. Rundstedt supported this view on operations in Poland in one of his rare commentaries following World War II. The bulk of the German armed forces had to be committed to overcome the Poles, and the expenditure in ammunition, gasoline, and materiel was such as to preclude concurrent German operations on a similar scale in the west or elsewhere.

The unrealistic impression of the campaign was heightened by the German propaganda effort that proceeded apace with operations in the field. The German armies were depicted as highly motorized, with tank support out of proportion to the actual number of armored vehicles they had available, and with fleets of aircraft supporting ground units on short notice with maximum efficiency. Little mention was made of the horse drawn supply columns, of the infantry divisions which often marched on foot at the rate of 30 miles per day, or of the repeated Luftwaffe bombings of advance German units.

The exaggeration of the picture of the new German war machine should not be construed to mean that the Wehrmacht was not a most effective fighting organization and had not accomplished much in putting the theory of mobile warfare to the test of battle. "Panzer" division and "Luftwaffe" soon became familiar terms in English and other foreign languages. It was obvious even to those not versed in military affairs that the era of trench warfare on the World War I pattern had ended. The element of movement had been restored to war, even though fewer than one in six of the German divisions mobilized during the period of the Polish Campaign were Panzer or motorized divisions. Except for the XVI and XIX Corps, the German Panzer force had also been committed piecemeal, and full ad vantage was not taken of the shock power of the Panzer division in the campaign in Poland.

The opportunity for a successful Allied attack against the Westwall had passed by the time the Polish Campaign ended. Hitler and his generals were well aware of the risk they had taken in throwing almost all their resources into the gamble for a quick victory in the east, as exemplified in their redeployment of divisions and higher commands from the Polish theater to the Westwall before operations in Poland had been completed.

The situation faced by the British and French in October 1939 was that of a fait accompli. Germany had defeated Poland completely and redeployed to the Westwall forces sufficient to withstand a belated Allied offensive. Adolf Hitler's success in Poland also enhanced the Fuehrer's opinion of his own abilities as a strategist and further encouraged him to deprecate the advice of his military staff and senior commanders. Germany's increasing strength and the continued in activity of the Western Allies soon inclined Hitler to order planning to commence for a fast-moving campaign to subjugate France and destroy the British Expeditionary Force. Only the onset of winter and the strongest objections from his military advisers prompted Hitler to delay his campaign until the following spring.

Lessons Learned by the Wehrmacht

The German forces took advantage of the opportunity to observe the effectiveness and utility of their new weapons and other materiel, organization, and tactics in combat operations in Poland and a number of improvements were found necessary. Some changes could be made before the campaign in France the following spring, while others would have to wait.

Materiel

Among the infantry weapons, the Model 1934 machine, gun was found to be subject to frequent stoppages in rugged field use, particularly in muddy or dusty areas. Research on a new machine gun was accelerated, and the Model 1942 that evolved would continue to operate despite exposure to many of the conditions that hampered the use of the Model 1934 weapon.

The higher rate of fire of the 1942 machine gun was to be of considerable significance in later operations. The effort expended by Germany in the development of artillery of all types was found to be justified. According to Colonel Blumentritt, operations officer for Rundstedt, the Poles themselves testified to the effectiveness of the German artillery fire in the attack on War saw. The defenders had received warning of air attacks with the appearance of German aircraft and the bombing had been of limited duration. The sustained artillery fire, however, wore down the resistance of the garrison of the Polish capital.

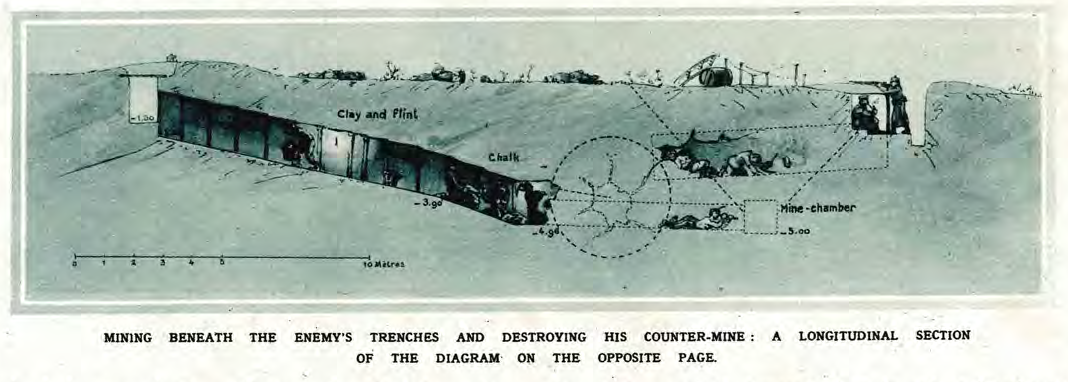

The 88mm antiaircraft gun was found to be especially effective in engaging bunkers and prepared fortifications. The VIII Corps made reference to this of the new gun in attacking the Polish fortifications at Nikolai. According to the VIII Corps account, the gun could penetrate the walls of bunkers and buildings reinforced as strongpoints.

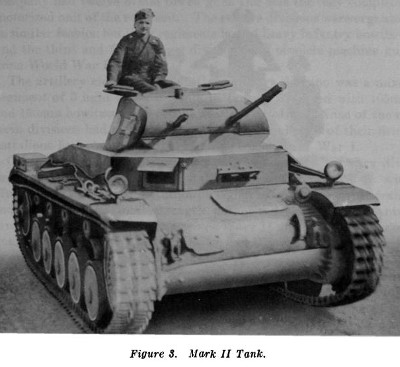

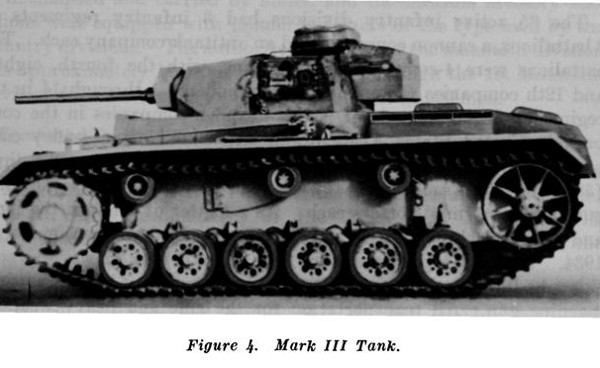

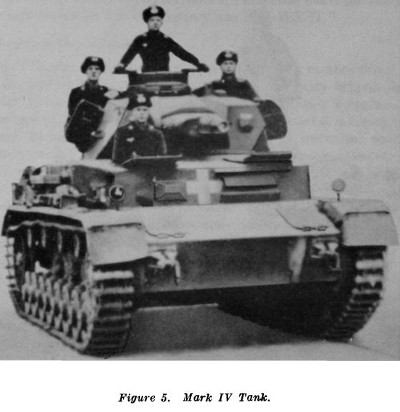

The German Mark I tanks were found to be unsatisfactory in operations, and the Mark II tanks were useful only for reconnaissance. This served to confirm the belief that these tanks were too light for operations and should be replaced by heavier types. Panzer units were henceforth equipped with a larger proportion of Mark III and Mark IV tanks. The heavier of the two, the Mark IV tank, was singled out by Guderian as a highly effective weapon to be produced in quantity. The Mark II tank was utilized for a time as a reconnaissance vehicle, and eventually the Mark I and II tank chassis were utilized as gun platforms for the self-propelled gun units organized for assault operations. In general, the supply of spare parts and system of maintenance for tanks was found to be inadequate for the needs of Panzer units in combat.

The rapid and overwhelming successes and light personnel losses of the new German tank force in the Polish Campaign, as illustrated by the movements of the XIX Corps across the Polish Corridor and from East Prussia to Brzesc, convinced Hitler of the effectiveness of this new weapon. In 10 days of operations the XIX Corps covered 200 miles in its drive on Brzesc. Polish reserve units still assembling in the rear areas were completely surprised and destroyed before they could organize a defense. In an action at Zabinka, east of Brzesc, elements of the XIX Corps interrupted the unloading of tanks at a rail siding and destroyed the Polish armored unit before is could deploy and give battle. The corps' losses totalled 2,236, including 650 dead, 1,345 wounded, and 241 missing, less than 4 percent of Guderian's entire force. Henceforth, as in the coming French Campaign, Panzer units were to play an increasingly important part in German planning.

Organization

Guderian recommended that battalion and regimental headquarters of Panzer units be located farther forward to direct the battle. Headquarters should be more mobile, restricted to a few armored vehicles, and well equipped with radio communication. The XIX Corps commander also recommended better communication with the supply columns and trains of the armored and motorized units.

The light divisions were found to have little staying power in sustained operations in Poland. These divisions already had at least one tank battalion each. The addition of a sufficient number of tanks to form a tank regiment for each division made it possible to complete the planned conversion of all four light divisions to Panzer divisions, bearing the numbers 6 through 9.

The motorized infantry divisions were found to be unwieldy in operations in Poland. To permit better control, one motorized infantry regiment was detached from each of the motorized divisions.

Equipment

Some infantry commanders complained of the awkward and heavy packs carried by the troops, recommending changes to permit the individual soldier greater freedom of action and more comfort. One commander recommended the carrying of machine gun ammunition by the ammunition carriers of gun crews in containers similar to those used by mortar crews, i.e., in a special pack carried by the individual soldier rather than in boxes carried by hand. This would permit the ammunition bearer to operate a rifle, giving the gun crew more protection and fire power. In addition a special grenade sack was recommended for the individual soldier. It was also requested that one rifleman in the infantry squad be provided with a telescopic sight to permit accurate fire on small or more distant targets.

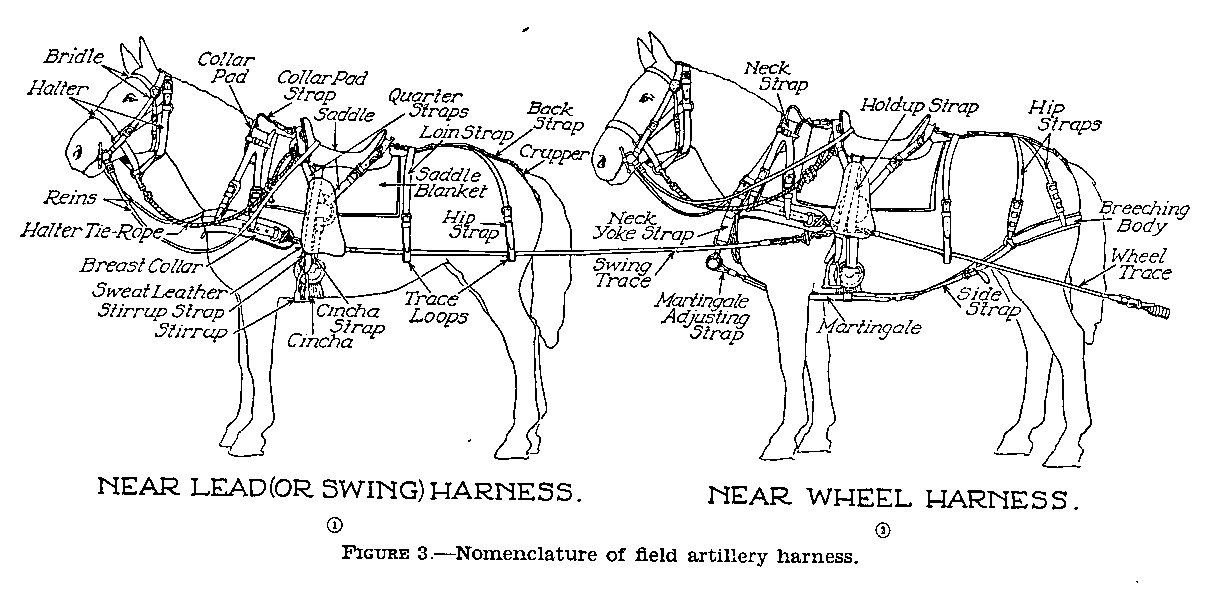

The 57th Infantry Division prepared a report on its experiences illustrating a number of the small oversights that added to the problems of the commanders of lower units. The division was a Wave II organization composed largely of reservists who had recently completed their periods of active service. During their two years of active duty, the men had been trained on the Model 1934 machine gun. When they were mobilized for the campaign in Poland, many did not know how to operate the older World War I type weapon with which some Wave II units were still equipped. Another oversight was the supply of horseshoes, made to a size common to military horses but far too small for the splayed hooves of many farm horses requisitioned at the time of mobilization.

Some fault was found with the equipment carried by assault engineers. Their heavy gear made it difficult for the engineers to carry out their assault role with the infantry. It was recommended that their equipment be so distributed that the engineers would be able to operate effectively as part of the infantry-engineer team in assault operations.

Training and Tactics

The infantry tactics of the Germans were criticized by Bock, who felt that too much was sacrificed to caution. This may seem somewhat contradictory, in view of the brief period of time in which the Ger mans destroyed a Polish force almost as strong as their own numerically and captured a number of heavily fortified areas that the Poles defended stubbornly. Bock actually had reference to the frequent delays incurred when artillery had to be brought forward to the sup port of infantry units. The general felt that some artillery batteries should always be attached directly to infantry units, to give close support in an attack or movement forward. The remainder of the artillery should be sufficiently mobile to move forward to support at tacking infantry with little delay. Bock expressed the opinion that the old adage "The infantry must wait for the artillery" should be changed to "The artillery may not delay the infantry."

Bock further felt that the German infantry training directives were obsolete and verbose. The commander of the northern army group was of the opinion that these regulations should be shortened and should stress the mission and aggressive action to accomplish it. Brief and pertinent regulations would be easier to remember and would impress on the officer, noncommissioned officer, and soldier the all-important task he was to perform in combat, with minimum distraction.

Another characteristic of warfare in eastern Europe as learned by the Germans was the considerable guerrilla activity in rear areas. As a consequence, it was recommended by a number of commanders that supply trains, workshops, and other rear installations be better equipped with weapons, particularly automatic weapons, and support personnel trained in their use.

The successful night attacks of the Poles made a considerable impression on the Germans. Although already aware of the advantage of moving by night, a device they used repeatedly, the Germans did not fully appreciate the potentialities of attacking under cover of darkness until shown by the Poles. With adequate security, these operations could cause considerable confusion when launched at the boundaries between units, as demonstrated by the Polish night attack of 12 September at the junction of the 207th Infantry Division and Brigade Eberhard lines before Gdynia.

Air Support

The Luftwaffe in Poland succeeded in proving its offensive power as an attack weapon, despite the protests of some senior army commanders whose troops had been bombed in close support operations. The Luftwaffe demonstrated its capabilities in isolating the Polish front by bombing bridges and rail lines, and preventing the movement of Polish supplies and troops by bombing and strafing truck columns on the roads. The Luftwaffe also rendered material assistance to advancing German armored columns and dive bombed Polish fortifications prior to attack by the ground forces. From this point the Luftwaffe was to have an important role as part of the German attack team.

The complete cover given ground forces by the Luftwaffe in Poland worked a disservice to the Army as far as camouflage was concerned. Despite instructions, there was little actual need for advancing units to utilize available cover and concealment at halts; for artillery to put up camouflage nets to hide guns, ammunition, and prime movers; or for command posts to limit vehicular traffic in their immediate vicinity. The Polish Air Force was unable to take advantage of this laxity on the part of many units, and the pace of the campaign made it impossible for higher commanders to take corrective action while operations were still in progress. As a consequence, a poor start in camouflage discipline was made by many units, and the lack of offensive action by the Polish Air Force made it impossible to point out examples of what might occur were the Wehrmacht to be committed against an enemy possessing an air force comparable to the Luftwaffe.

On assembling his men the officer commanding should personally inspect each man, and ascertain that he has proper articles of clothing under his uniform, and that he is provided with suitable boots for marching.

On assembling his men the officer commanding should personally inspect each man, and ascertain that he has proper articles of clothing under his uniform, and that he is provided with suitable boots for marching.

Interrogation of Fianale Fappen, of NEUENAHR.

Interrogation of Fianale Fappen, of NEUENAHR.

Combat Lessons, Number 2, September 1946

Combat Lessons, Number 2, September 1946

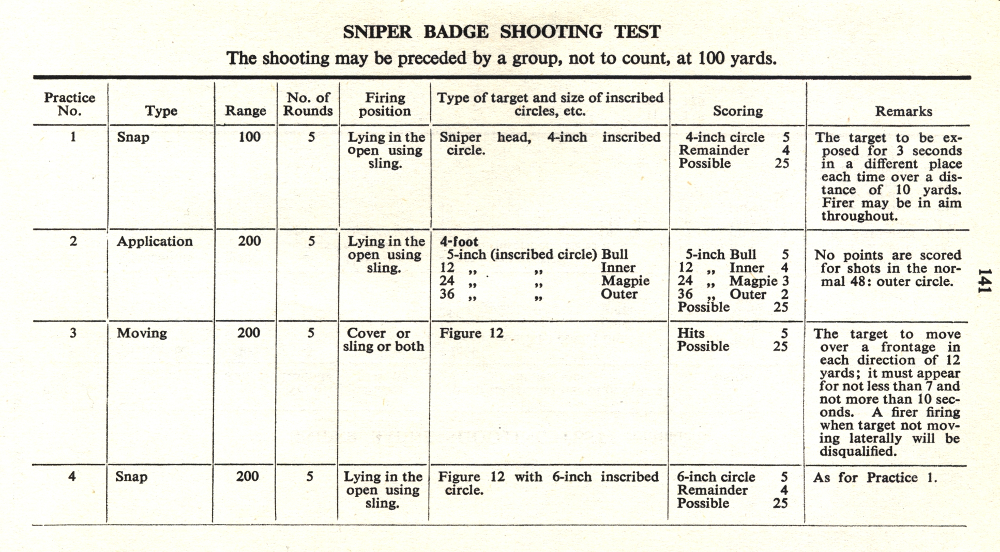

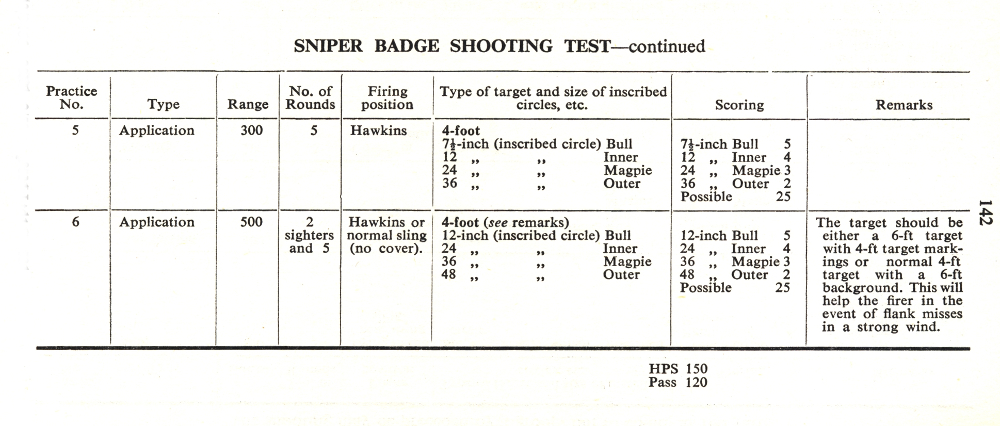

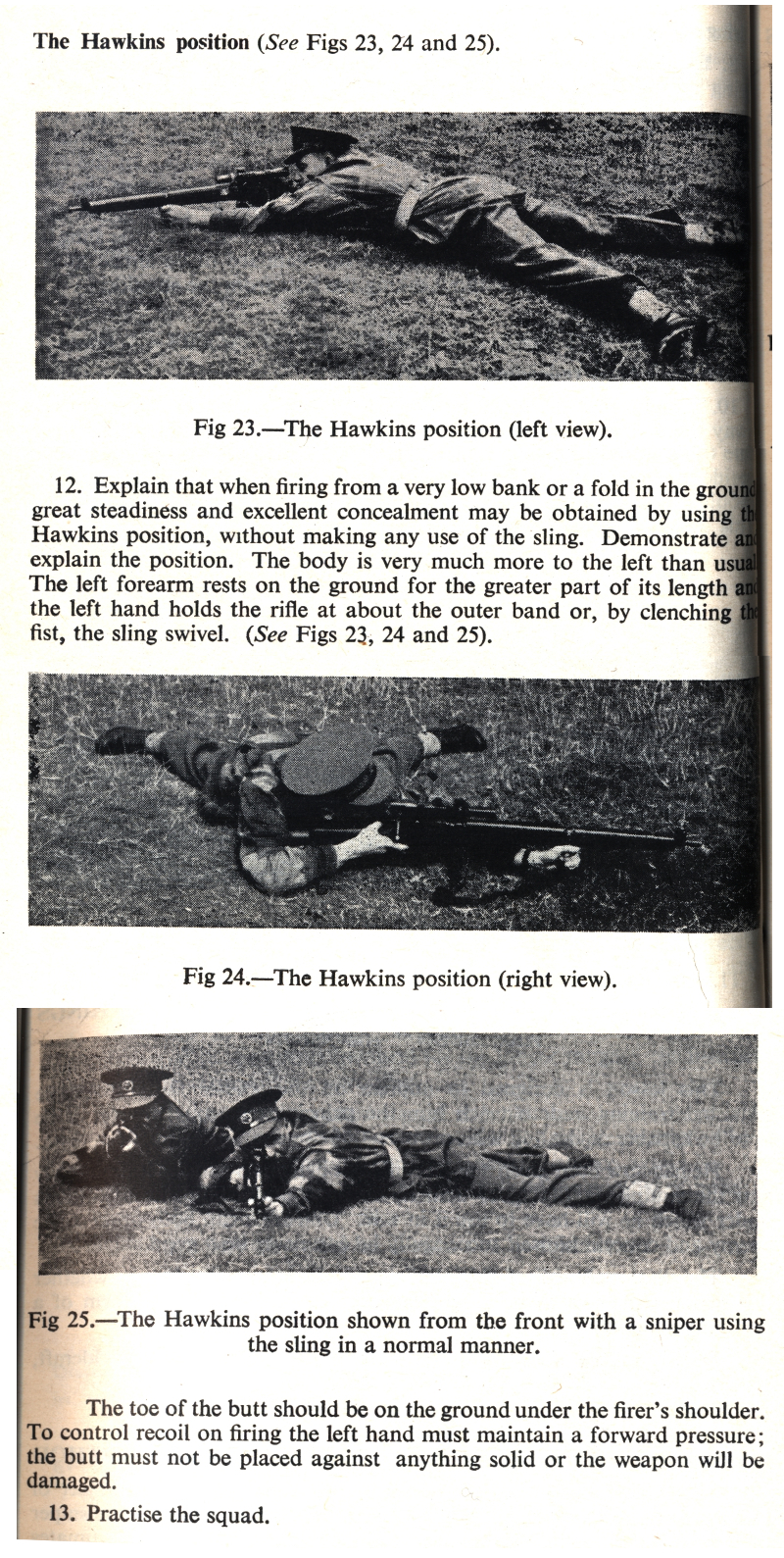

Sniper Badge Shooting Test (1951)

Sniper Badge Shooting Test (1951)