Topic: Canadian Militia

Canada's Militia; Thoroughly Demoralized

The Service in a Thoroughly Demoralized Condition

The Result of Departmental Mismanagement

What Militia officers Say Borne out by a Chicago Critic

The Montreal Herald and Daily Commercial Gazette, 29 January 1890

Some five or six weeks ago there appeared in the local columns of The Herald several articles, the substance of interviews with militia officers, pointing out the demoralized condition of the militia service, the unpreparedness of the men for active service at short notice, the unserviceableness of their equipment, including their rifles, and the consequent general waste of money spent by the Militia Department. No one has undertaken to call the statements made in question, simply because they were true, as many of our most public-spirited officers are quite ready to admit. A clipping bearing on this question, and which was published in a Chicago paper ten years ago, is appended. It is somewhat overdrawn, but, making allowance for exaggeration, it fully bears out the statements made in this paper referred to above. The clipping is as follows:—

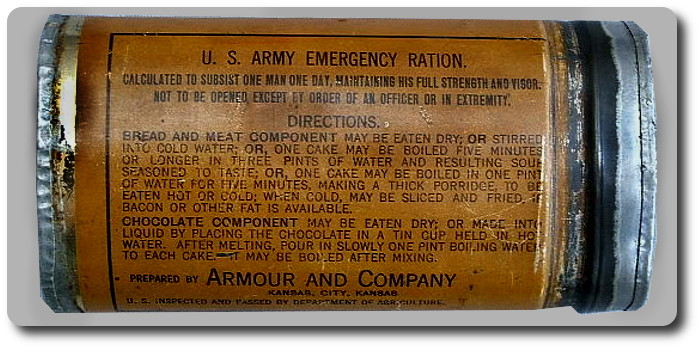

"The Canadian Militia [circa 1880] is divided into two parts, the active and what is called the reserve. The total number of the active militia is about 42,000 men. Of this number about one half drill for twelve days each year, for which each militiaman receives $6. the corps are made up of city and country battalions, and as the authorities think the city corps are the most useful, they always give them the preference, and all the city corps are allowed to put in their annual drill. These corps, in round numbers, muster about 10,000 men, and thus the remaining 11,000 who are entitled to drill are selected by rotation, year after year. No country corps drill two years in succession, and many of them have been three, or even four years without having a muster. In the cities some of the corps are fairly efficient in drill. The men are clean, well dressed, obedient and willing. No one can find a reasonable fault with the rank and file of the Canadian militia, and in physique they stand comparison with any troops in the world. The climate makes them hardy, and more than once they have proved themselves of use to the State. But here it ends. Of internal economy the majority of the corps know nothing. There is not a semblance of a commissariat in the whole Dominion. There are simply 21,000 good men in uniform provided each year, put through a few evolutions, and there is the beginning and end of it. The officers make heroic sacrifices the keep their corps efficient; the State makes political capital out of the service, and so it goes on from one year to the other. There is not an ambulance wagon in Canada, and the medical staff is a fiction. In the principal city in the Dominion the militia are without a drill-shed, and the men are obliged to drill in places which, in your country, would only be regarded as fit for hen-roosts. With all this there are some good corps—the Queen's Own, of Toronto, undoubtedly coming first; then there is the Montreal brigade, the Eighth Quebec, the Governor-general's Guards and a couple of other troops in Ontario. But still these 21,000 are, all things considered, fairly efficient. Now, as for the country corps in general, they are, in most cases, men in uniform—nothing more and nothing less. The money spent on them is too often money thrown away. They meet, they love, and they are parted, knowing no more of their duties than could be gathered by two days' drill under the hands of an experienced instructor. This is no assertion of mine. It is almost word for word what the General in command (Luard) told a country corps near Quebec a few days ago. But they are there, and they are ready, and if required could soon be equipped into shape, but at present they count for little and they show for less. The officers are miserably deficient in their duties, the arms are in bad order, the equipment is far from serviceable and none of the troops are supplied with the Martini-Henry rifle. But let us grant that there are 42,— fairly equipped men. If put to the test no doubt these men would respond with alacrity and would submit to the discipline necessary to get them into shape with resignation. But here is the beginning and the end of the Canadian militia. As for reserve, there is none. When I say none, I mean none—not one mother's son. The reserve of the Dominion is a delusion, and it has no more existence than the man in the moon. But in order to impose on themselves, or the outside world, I know not which, a number of colonels, majors, captains and others appear in the army list as belonging to the reserve militia, while of that militia there is not, I venture to say, a muster-roll in the country. It does not exist even on paper, except that the officers are duly gazetted. These officers never had a uniform on their backs, never saw the men they are supposed to command, and they laugh at the thing as a huge joke. Marshal Saxe once said that it was legs, not arms, that won campaigns, but the Canadian militia reserve has neither legs nor arms. A stranger to the country who takes up the army list and counts 250 men for each Lieutenant Colonel on the reserve militia might, I suppose, count 400,000 or 500,000 men, but if a militia reserve can be manufactured by simply placing a certain number of names on the army list, then good-bye statistics for ever. Here is the condition of the Canadian militia. There are 42,000 men, all told. If these 42,000 there are about 21,000 fairly efficient, while the remaining 21,000 drill, on an average, six days in two or say three years. But to put it in round numbers, we call out 42,000 men, and good men too, but that is the strength, stock, lock, and barrel of the service, and it is to that that the 600,000 vanish like a dream."

Issue of Battle Lists

Issue of Battle Lists

Ottawa, Oct. 5.—The South African mail, which arrived to-day, brought several reports to the Militia Department.

Ottawa, Oct. 5.—The South African mail, which arrived to-day, brought several reports to the Militia Department.

Reports from various parts of the country state that a larger percentage of native born Canadians are enlisting in the second contingent than went out with the first. In the first contingent it is said that only thirty per cent. of those who volunteered were native born Canadians, the remainder being British born, many of whom had some previous military training. Another factor noticeable in connection with the recruits for the second contingent is that they are a better type of men. The first contingent was largely made up of adventurers, while the recruits for the second contingent consist very largely of men holding responsible positions, who are throwing these up and going to the front from a sense of duty. Hundreds of college men will go out with the second contingent, while numbers of college professors from different universities have enlisted and are taking their places in the ranks. Business men from big corporations, banks, farmers' sons and others are vieing with one another in rallying to the call for men.

Reports from various parts of the country state that a larger percentage of native born Canadians are enlisting in the second contingent than went out with the first. In the first contingent it is said that only thirty per cent. of those who volunteered were native born Canadians, the remainder being British born, many of whom had some previous military training. Another factor noticeable in connection with the recruits for the second contingent is that they are a better type of men. The first contingent was largely made up of adventurers, while the recruits for the second contingent consist very largely of men holding responsible positions, who are throwing these up and going to the front from a sense of duty. Hundreds of college men will go out with the second contingent, while numbers of college professors from different universities have enlisted and are taking their places in the ranks. Business men from big corporations, banks, farmers' sons and others are vieing with one another in rallying to the call for men.

Rum as a Stimulant

Rum as a Stimulant

Next to the forming of troops, military discipline is the first object that presents itself to our notice. It is the soul of all armies; and unless it be established amongst them with great prudence, and supported with unshaken resolution, they are no better than so many contemptible heaps of rabble, which are more dangerous to the very state that maintains them, than even its declared enemies.

Next to the forming of troops, military discipline is the first object that presents itself to our notice. It is the soul of all armies; and unless it be established amongst them with great prudence, and supported with unshaken resolution, they are no better than so many contemptible heaps of rabble, which are more dangerous to the very state that maintains them, than even its declared enemies.

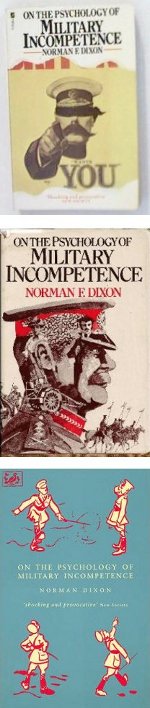

Norman Dixon's book looks at incompetence in military leaders throughout history and considers whether, rather than being random occurrences, they are, in fact, a result of the military system. In particular he considers whether people with certain psychological characteristics are drawn to a military career, and whether the military insulates and exacerbates these characteristics in them.

Norman Dixon's book looks at incompetence in military leaders throughout history and considers whether, rather than being random occurrences, they are, in fact, a result of the military system. In particular he considers whether people with certain psychological characteristics are drawn to a military career, and whether the military insulates and exacerbates these characteristics in them.

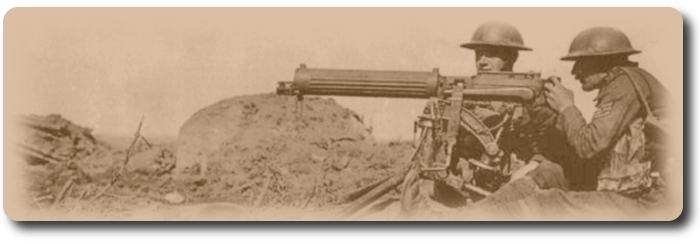

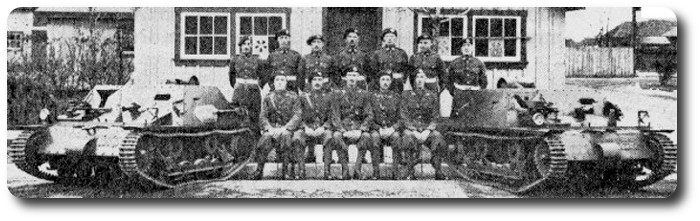

Modern weapons of war, as applicable in particular to the protection and support of infantry on the offensive, were discussed last night by

Modern weapons of war, as applicable in particular to the protection and support of infantry on the offensive, were discussed last night by