Recon Patrol Tips, Vietnam, 1970

Topic: Drill and Training

Recon Patrol Tips

Combat Recon Manual, Republic of Vietnam; 1970

Combat Recon Manual, Republic of Vietnam; 1970

Prepared by Project (B-52) Delta, H.Q. NhaTrang

Detachment B-52; 5th Special Forces Group (Abn), 1st Special Forces

1. When making VRs always mark every LZ within your AO and near it, on your map. Plan the route of march so that you will always know how far and on what azimuth the nearest LZ is located.

2. Don't cut off too much of the map showing your recon zone (RZ). Always designate at least 5-10 kilometers surrounding your RZ as running room.

3. Base the number of canteens per man upon the weather end availability of water in the AO. Select water points when planning your route of march.

4. Check all team members' pockets prior to departing home base for passes, ID cards, lighters with insignias, rings with insignias, etc. Personnel should only carry dog tags while on patrol.

5. If the team uses a grenadier armed with rifle grenades, hare him place a crimped cartridge as the first round in each magazine carried. After firing the grenade, he can use the rifle normally. When the magazine is empty and a new one inserted the grenadier can then quickly fire another grenade.

6. Always carry maps and notebooks in waterproof containers.

7. Use a pencil to make notes during an operation. Ink smears when it becomes wet whereas lead does not.

8. Inspect each team member's uniform and equipment, especially radios and strobe lights prior to departure on a mission

9. If you use the Hanson Rig, adjust your harness and webbing before leaving on patrol.

10. During the rainy season take extra cough medicine and codeine on patrol.

11. The location and proper use of morphine should be known by all team members.

12. All survival equipment should be tied or secured to the uniform or harness to prevent loss if pockets become torn, etc.

13. Each US or key team member should carry maps, notebooks, and SOI in the same pocket of each uniform, for hasty removal by other team members if one becomes a casualty.

14. Take paper matches to the field in waterproof container. DO not take cigarette lighters as they make too much noise when opening and closing.

15. Tie panel and mirror to pocket flap to prevent losing.

16. Always carry rifle cleaning equipment on operations, i.e., brush, oil and at least one cleaning rod.

17. Each team should have designated primary and alternate rally points at all times. The team leader is responsible for ensuring that each team member knows the azimuth and approximate distance to each rally point / LZ.

18. Never take pictures of team members while on patrol. If the enemy captures the camera, they will have gained invaluable intelligence.

19. At least two penlights should be taken by each team.

20. While on patrol, move 20 minutes and halt and listen for 10 minutes. Listen half the amount of time you move. Move and halt at irregular intervals.

21. Stay alert at all times. You ore never 100% safe until you are back home.

22. Never break limbs or branches on trees, bushes, or palms, or you will leave a very clear trail for the enemy to follow.

23. Put insect / leech repellent around tops of boots, on pants fly, belt, and cuffs to stop leeches and insects.

24. Do most of your moving during the morning hours to conserve water, however never be afraid to move at night, especially if you think your RON has been discovered.

25. Continually check your point man to ensure that he is on the correct azimuth. Do not run a compass course on patrol, change direction regularly.

26. If followed by trackers, change direction of movement often and attempt to evade or ambush your trackers, they make good Pws.

27. Do not ask for a "fix" from FAC unless absolutely necessary. This will aid in the prevention of compromise.

28. Force yourself to cough whenever a high performance aircraft posses over. It will clear your throat, ease tension and cannot be heard. If you must cough, cough in your hat or neckerchief to smother the noise.

29. Never take your web gear off, day or night. In an area where it is necessary to put the jungle sweater on at night, no more than two patrol members at a time should do so. Take the sweaters off the next morning to prevent cold and overheating.

30. If you change socks, especially in the rainy season, try to wait until RON and have no more than two patrol members change socks at one time. Never take off both boots at the same time.

31. When a team member starts to come down with immersion foot, stop In a secure position, remove injured persons boot, dry off his feet, put foot powder on his feet and place a ground sheet or poncho over his feet so that they can dry out, Continued walking will make matters worse, ensuring that the man will become a casualty, thereby halting the further progress of the team.

32. Desenex or Vaseline rubbed on the feet during the rainy season or in wet weather will aid in the prevention of immersion foot. It will also help avoid chapping if put on the hands.

33. Gloves will protect hands from thorns and aid in holding a weapon when it heats up from firing.

34. Place a plastic cover on your PRC-25 to keep it dry in the rainy season.

35. When using a wiretap device, never place the batteries in the set until needed. If the batteries are carried in the device they will lose power even though the switches are in the off position.

36. If batteries go dead or weak do not throw them away while on patrol. Small batteries can be recharged by placing them in armpits or between the legs of the body. A larger battery can gain added life by sleeping with the battery next to the body. Additional life can also be gained by placing batteries in the sun.

37. If possible, carry an extra hand set for the PRC-25 and ensure that it is wrapped in a waterproof container.

38. Always carry a spare PRC-25 battery, but do not remove the spare from its plastic container prior to use or it may lose power.

39. Do not send "same" or "no charge" when reporting team location. Always send your coordinates. Keep radio traffic at a minimum.

40. Avoid over confidence, it leads to carelessness. Just because you have seen no sign of the enemy for 3 or 4 days does not mean that he isn't there or hasn't seen you.

41. A large percentage of patrols have been compromised due to poor noise discipline.

42. Correct all team and / or individual errors as they occur or happen.

43. All personnel should camouflage faces and bocks of hands in the morning, at noon and at RON or ambush positions.

44. Never cook or build heating fires on patrol. No more than two persons should eat chow at any one time. The rest of the team should be on security.

45. When team stops, always check out to 40-60 meters from the perimeter.

46. All team members should take notes while on an operation and compare them nightly. Each man should keep a list of tips and lessons learned and add to them after each operation.

47. Each man on a team must continually observe the man in front of him and the men behind him, in addition to watching for other team members' arm and hand signals.

48. A recon team should never place more than one mine. AP, or AT, in one small section of o road or trail at a time. If more than one is set out the team is just resupplying the enemy, because when a mine goes off, a search will be made of the immediate area for others and they will surely be found.

49. During the dry season, do not urinate on rocks or leaves but rather in a hole or small crevice. The wet spot may be seen, and the odor will carry further.

50. When carrying the M79 on patrol, use a retainer band around the stock to hold the safety on safe while moving.

51. When crossing streams, observe first for activity, then send a point man across to check the area. Then cross the rest of the patrol, with each taking water as he crosses. If in a danger area, have all personnel cross prior to getting water. Treat all trails (old and new), streams, and open areas as danger areas.

52. Carry one extra pair of socks, plus foot powder, on patrol, especially during the rainy season. In addition, each team member should carry a large sized pair of socks to place over his boots when walking or crossing a trail or stream.

53. During rest halts don't take your pack off or leave your weapon alone. During long breaks, such as for noon chow, don't take your pack off until your perimeter has been checked for at least 40 to 60 meters out for 360 degrees. During breaks throw nothing on the ground. Either put trash in your pocket or spray it with CS powder and bury it.

54. In most areas, the enemy will send patrols along roads and major trails between the hours of 0700-1000 and from 1500- 1900. Since most of the enemy's vehicular movement is at night, a team that has a road watch mission should stay no less than 200 meters from the rood during the day and move up to the road just prior to last light. When the enemy makes a security sweep along a road, usually twice a week, he normally does not check further than 200 meters to each flank.

55. If you hear people speaking, move close enough to hear what they are saying. The reason is obvious. The VN team leader should make notes.

56. While on patrol, don't take the obvious course of action and don't set a pattern in your activities, such as, always turning to the left when "button hooking to ambush your own back trail.

57. A dead enemy's shirt and contents in pockets, plus pock, if he has one, are normally more valuable than his weapon.

58. If the enemy is pursuing you, you should deploy delay grenades and/or delay claymores of 60-I20 seconds. In addition, throw CS grenades to your rear and flanks. Give he enemy a reason and or excuse to quit.

59. Do not fire weapons or use claymores or grenades if the enemy is searching for you at night. Use CS grenades instead. This will cause him to panic and will not give your position away, you can move out In relative safety while they may end up shooting each other. If claymores become necessary, use time delayed claymores or time delayed WP.

Posted by regimentalrogue

at 12:01 AM EDT

Combat Recon Manual, Republic of Vietnam; 1970

Combat Recon Manual, Republic of Vietnam; 1970

It's the Army's revolutionary new way of dealing with rations.

It's the Army's revolutionary new way of dealing with rations.

The Army formally adopted a set of Principles of War in 1921 that endure today. Briefly stated they are:

The Army formally adopted a set of Principles of War in 1921 that endure today. Briefly stated they are:

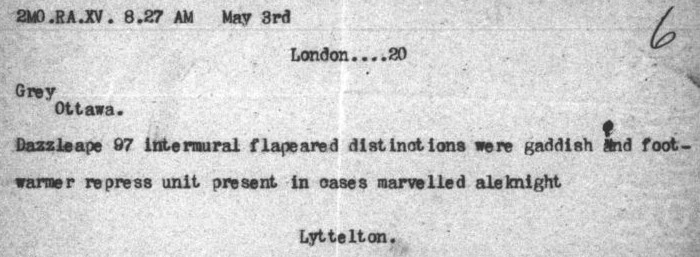

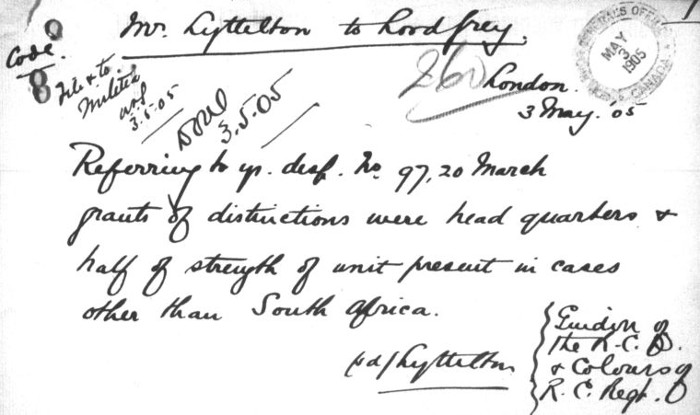

I have the honour to inform you that in considering the historical significance of the cap badge of the

I have the honour to inform you that in considering the historical significance of the cap badge of the

In a war of revolutionary character, guerrilla operations are a necessary part. This is particularly true in a war waged for the emancipation who inhabit a vast nation.

In a war of revolutionary character, guerrilla operations are a necessary part. This is particularly true in a war waged for the emancipation who inhabit a vast nation.

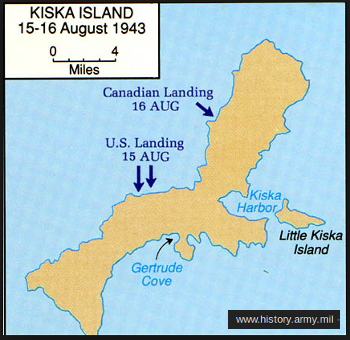

U.S. rations used by the Canadian troops during

U.S. rations used by the Canadian troops during

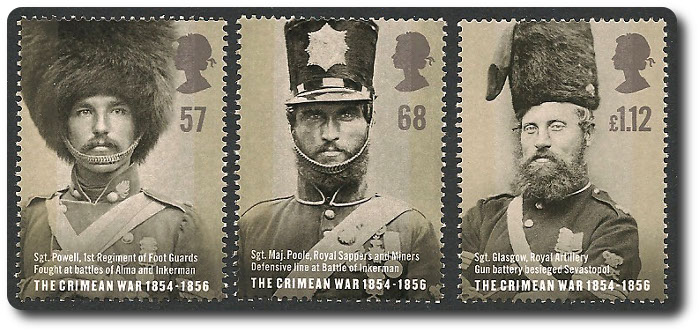

London, Sep. 22.—A worthless scoundrel, who deserted to the enemy from the English ranks when before Sebastopol, and by his treachery caused the slaughter of a number of his comrades, has just been captured, and awaits sentence of a court-martial. On the 22d of March, 1855, the 7th Regiment of Fusiliers were performing trench duty, when two of the men, Private Thomas Tole, and a companion named Moore, left the lines under pretence of searching for fuel, and instead of returning, went over to the enemy. The treacherous information they gave of the position of the company they had deserted from, proved a guide to the Russians, who, making a determined attack upon them the same night, killed Captain the Hon. Cavendish Brown and thirty men. Tole was not given up with the exchange of prisoners at the end of the war, but went to St. Petersburg. Desiring, subsequently, to return to England, he contrived to obtain a passport, and has been for some time in York. More recently he took up his quarters in old Mount Street, Manchester. Several months ago, Mr. Leary, superintendent of the B division, had him taken into custody on suspicion of being guilty of this heinous and disgraceful offence, but the evidence failed to prove his desertion. Later correspondence with the commanding officer, however, led to the production of witnesses who could speak more positively; and on Monday Tole was again placed before the city magistrate, when two of his former comrades in the same company, to whom he was personally known, gave evidence regarding his going over to the enemy, and he was ordered to be delivered over to the military authorities. Tole is a native of Ireland, and 24 years of age. A man of the same regiment, named Dennis Cleary, who was wounded, and has since received his discharge, is now a police officer in the B division. Tole states that his companions, Moore, died in two days after they joined the Russians. (Manchester Examiner)

London, Sep. 22.—A worthless scoundrel, who deserted to the enemy from the English ranks when before Sebastopol, and by his treachery caused the slaughter of a number of his comrades, has just been captured, and awaits sentence of a court-martial. On the 22d of March, 1855, the 7th Regiment of Fusiliers were performing trench duty, when two of the men, Private Thomas Tole, and a companion named Moore, left the lines under pretence of searching for fuel, and instead of returning, went over to the enemy. The treacherous information they gave of the position of the company they had deserted from, proved a guide to the Russians, who, making a determined attack upon them the same night, killed Captain the Hon. Cavendish Brown and thirty men. Tole was not given up with the exchange of prisoners at the end of the war, but went to St. Petersburg. Desiring, subsequently, to return to England, he contrived to obtain a passport, and has been for some time in York. More recently he took up his quarters in old Mount Street, Manchester. Several months ago, Mr. Leary, superintendent of the B division, had him taken into custody on suspicion of being guilty of this heinous and disgraceful offence, but the evidence failed to prove his desertion. Later correspondence with the commanding officer, however, led to the production of witnesses who could speak more positively; and on Monday Tole was again placed before the city magistrate, when two of his former comrades in the same company, to whom he was personally known, gave evidence regarding his going over to the enemy, and he was ordered to be delivered over to the military authorities. Tole is a native of Ireland, and 24 years of age. A man of the same regiment, named Dennis Cleary, who was wounded, and has since received his discharge, is now a police officer in the B division. Tole states that his companions, Moore, died in two days after they joined the Russians. (Manchester Examiner)