Ragging in the British Army

Topic: Officers

Ragging in the British Army

1903

Ragging a Colonial

Court Martial in Dublin Against Certain Officers of the 21st Lancers

Ottawa Citizen, 14 May 1903

London, May 12.—A court-martial is in progress at Dublin against certain officers of the 21st Lancers. They are accused of "ragging" a brother officer, Lieutenant Willows. Lord Roberts is in Dublin today and is especially interesting himself in the trial. Williams is a colonial ranker who gained his commission through heroism displayed in the South African war. He takes his profession seriously. His brother officers ragged him first because he had risen from the ranks, and secondly because he is a colonial. This kind of a scandal is common in many regiments where commissions are held by colonial rankers. The ordinary English soldier considers the army a social preserve and not a public service.

London, May 12.—A court-martial is in progress at Dublin against certain officers of the 21st Lancers. They are accused of "ragging" a brother officer, Lieutenant Willows. Lord Roberts is in Dublin today and is especially interesting himself in the trial. Williams is a colonial ranker who gained his commission through heroism displayed in the South African war. He takes his profession seriously. His brother officers ragged him first because he had risen from the ranks, and secondly because he is a colonial. This kind of a scandal is common in many regiments where commissions are held by colonial rankers. The ordinary English soldier considers the army a social preserve and not a public service.

1904

"Ragging" in the Army

A Threat of Cashiering

The Age, Melbourne, 9 May 1904

London, 7th May.—The disclosures made some months ago in connection with the occurrences of serious "ragging" scandals amongst the officers in certain British regiments have led the Army Council to issue a strong memorandum on the subject, in which it threatens that if there is any repetition of "ragging" the names of the perpetrators will be submitted to His Majesty the King, with a view to their removal from the army.

Rites of the Military "Rag"

A Cure for Ambition

The Age, Melbourne, 17 March 1903

(From Our Correspondent)

London, 13th February.—The whole absurd story of how the fashionable young bloods of the Grenadier Guards maintain what they conceive to be "good form" is now public property. It is a present to the comic playwrights. They will not be able to make use of it in London, for London has a mysterious reverence for bear skins and pipeclay and a not very robust sense of humor, but some travesty of the affair may be expected to find its way on to the stage of Paris or new York before long. Hitherto we have depended mainly upon the gossip of West End clubs for accounts of the mock inquisition, the arrests, farcical charges, and disciplinary flagellations practiced in the regiment. Fuller details have now been collected, drawn up in deliberate form and circulated among the members of both Houses of Parliament and the press.

London, 13th February.—The whole absurd story of how the fashionable young bloods of the Grenadier Guards maintain what they conceive to be "good form" is now public property. It is a present to the comic playwrights. They will not be able to make use of it in London, for London has a mysterious reverence for bear skins and pipeclay and a not very robust sense of humor, but some travesty of the affair may be expected to find its way on to the stage of Paris or new York before long. Hitherto we have depended mainly upon the gossip of West End clubs for accounts of the mock inquisition, the arrests, farcical charges, and disciplinary flagellations practiced in the regiment. Fuller details have now been collected, drawn up in deliberate form and circulated among the members of both Houses of Parliament and the press.

The most astonishing narrative is that supplied by Rear Admiral Basil Cochrane, whose nephew, Mr. J.H. Leveson-Gower, and exceptionally promising young officer, has been compelled to resign from the regiment in consequence of the tyrannies inflicted upon him—partly, it would seem, because, like Lieutenant Gregson, the victim of the Life Guards' "rag" at Windsor, he showed an unseemly desire to attend to his work. Rear Admiral Cochrane explains that his story has been most carefully written; every important statement it contains can be sworn to, if necessary. When "ragging" in the Brigade of Guards (in which the Grenadiers are included) has come under public notice, it has been the custom of those who try to excuse it—for it has its apologists in certain newspapers which cater to the old fogeydom of the military profession—to allege that the commanding officers were not aware of the practice. The bulk of the evidence produced in these recent cases, however, disposes of that assertion pretty conclusively. Indeed, it now appears that it has been the habit of the senior officers—at least of those in the Grenadiers—to encourage "ragging." Subalterns' court-martials have existed for some years for the trial of young officers on any charges brought against them, either of a social or military character.

The general procedure is described as follows:—"The court consists of a president (the senior subaltern) and two members, the attendance of all other subalterns being exacted. They were held much more frequently in the 1st battalion than in the others, and in the 1st battalion the colonel was in the habit to use the consecrated term, of 'handing over' young officers to be dealt with by the senior subaltern, which nearly invariably resulted in their being sentenced by this irregular tribunal to be flogged. This flogging was administered over the lower part of the back, which was bared for punishment by the removal of their nether garments, and blows of great severity applied with a cane or stick in numbers varying from six to forty. A young officer last year who received the latter number fainted under the cruel severity of the punishment; but even six blows with the instrument employed were sufficient to make blood flow, as was constantly the case. What greatly added to the inhumanity of these proceedings was that all officers present were compelled to administer their share of the strokes if numbers permitted, and comrades were obliged to apply blows to their own personal friends under threats of receiving similar punishment themselves. If a young officer, in commiseration of his friend, applied a stroke considered too light by the president, he was called upon to repeat the blow."

On entering the army, fresh from Oxford, about two years ago, Mr. Leveson-Gower threw himself with ardor into his work. He read military history, took up the study of the Russian language, and went through a special course of signalling. A battalion trained by him obtained the highest position as signallers in England. Presently he became himself acting signalling officer for the Home District, and in this capacity took a large share in the management of last year's royal processions in London. In the midst of his work he tripped simply, yet grievously, from the red tape and pipeclay point of view. Wishing to go up to Scotland for a few days he asked and obtained leave from the chief staff officer under whose immediate orders he was then serving. But he omitted to obtain leave also from Colonel Kinloch, the commanding officer of his battalion. When he had been two days absent the colonel recalled him by telegram, reprimanded him for being "absent without leave" and finally (his uncle states) "told him he would be handed over to the senior subaltern." Knowing that this meant a flogging, Gower asked to see General Sir Harry Trotter, on whose staff he was serving. Kinloch, it is stated, then put him under arrest.

The next stage of this farce may be given in Rear Admiral Cochrane's own language:—"Brought before the subalterns' court-martial, the president told him that he had been handed over to him by the commanding officer. Evidence on oath as to this can be obtained from many of the officers present. He was found guilty of causing trouble to his commanding officer, and sentenced to be beaten. Whether the members of the court disapproved of flogging for military offences and considered the colonel's punishments already quite sufficiently severe, or whether they were influenced by the character of my nephew as a good comrade, it is a fact that unusual consideration was displayed in his case. He was not subjected to the degrading removal of his dress, and the blows which he received were of no excessive severity." A "knotted cane" was used in inflicting the punishment. Gower's real troubles, however, began after this incident. He tried to get redress from Kinloch's superiors, but they stood by the colonel to a man on grounds of etiquette and for the protection of then "ragging" machine. The senior subalterns appear to have been emboldened by this support, for a little later they warned Gower and two other juniors that "unless they rode with the brigade 'drag' at Windsor, they would be flogged." It will be seen that the statements made in this case put an entirely different aspect on Colonel Kinloch's position from that which it bore when the announcement was first made of his compulsory retirement from the regiment. It was said then, and by most people believed, that he was not aware of the practices of the subalterns' court-martial. Evidently Lord Roberts knew better; hence his peremptory punishment of the colonel. This punishment, and what it implies—coming from a man who is by no means a martinet—will doubtless remain, whatever may be said on the subject in Parliament. Possibly Gower broke regimental rules in one way or another, though this is not admitted by his uncle. At least it is clear that nothing was conceded to him by any of his superiors on the score of youth and inexperience. The regiment became intolerable to him, as his persecutors probably intended that it should, and he accordingly sent in his papers.

1906

Army "Ragging" Case

Six Officers Punished

The Age, Melbourne, 24 April 1906

London, 22nd April.— In conformity with the instructions given by Mr. Haldane, Secretary of State for War, a strict investigation has been made into the circumstances of the case of "ragging" which occurred last month in consequence with the First Battalion of the Scots Guards, stationed at Aldershot. A young lieutenant was seized by other officers and smeared with motor oil, while his hair was covered with jam, and he was otherwise so maltreated as to cause a nervous breakdown.

London, 22nd April.— In conformity with the instructions given by Mr. Haldane, Secretary of State for War, a strict investigation has been made into the circumstances of the case of "ragging" which occurred last month in consequence with the First Battalion of the Scots Guards, stationed at Aldershot. A young lieutenant was seized by other officers and smeared with motor oil, while his hair was covered with jam, and he was otherwise so maltreated as to cause a nervous breakdown.

As a result of a court martial, Colonel C.J. Cuthbert has been relieved of his command, and Captain R.G. Stracey of his adjutancy. Four lieutenants who were arrested at the time of the discovery of the outrage will each lose a year's seniority.

The lieutenant who was "ragged" has left the regiment. It is now evident that the treatment to which he was subjected was not, as was first reported, owing to his being unable to live in the same expensive manner as his colleagues, but was provoked in consequence of a doctor's report that the young officer was suffering from an unpleasant disease, due to his personal habits.

There is a consensus of opinion on the part of the newspapers in discussing the Scots Guards scandal, that the judgment given by the court-martial will operate effectively in the suppression of "ragging."

"Ragging" in the British Army

The Age, Melbourne, 29 May 1906

(From Our Correspondent)

London, 27th April.— Caste influence in the army has always been, either tacitly or openly, on the side of ragging as a means of inculcating the gospel of good form, including the good form which consists in avoiding hard work. That is why it seemed natural to Colonel Cuthbert to hand over Lieutenant Clark Kennedy "to be dealt with by his brother subalterns" in the Scots Guards, in spite of an order issued some time ago by the Army Council (which has found that it cannot afford to represent society feeling in such matters), making it clear that commanding officers would be held to strict account for the maintenance of discipline in their regiments. The colonel should have reported the case to headquarters. Had he done so the offence alleged against Kennedy, which was not clearly proved, and was not a breach of military discipline, might have been visited only with a reproof, and in that case the other lieutenants whose over-refined susceptibilities he had ruffled might have been obliged to tolerate his society for a further period. At the official inquiry the colonel professed surprise at what had happened, but naturally this did not much impress anyone. He had practically sanctioned the degrading attack on Kennedy, and it took the form rendered familiar by scores of previous examples of private punishment and coercion in fashionable regiments.

London, 27th April.— Caste influence in the army has always been, either tacitly or openly, on the side of ragging as a means of inculcating the gospel of good form, including the good form which consists in avoiding hard work. That is why it seemed natural to Colonel Cuthbert to hand over Lieutenant Clark Kennedy "to be dealt with by his brother subalterns" in the Scots Guards, in spite of an order issued some time ago by the Army Council (which has found that it cannot afford to represent society feeling in such matters), making it clear that commanding officers would be held to strict account for the maintenance of discipline in their regiments. The colonel should have reported the case to headquarters. Had he done so the offence alleged against Kennedy, which was not clearly proved, and was not a breach of military discipline, might have been visited only with a reproof, and in that case the other lieutenants whose over-refined susceptibilities he had ruffled might have been obliged to tolerate his society for a further period. At the official inquiry the colonel professed surprise at what had happened, but naturally this did not much impress anyone. He had practically sanctioned the degrading attack on Kennedy, and it took the form rendered familiar by scores of previous examples of private punishment and coercion in fashionable regiments.

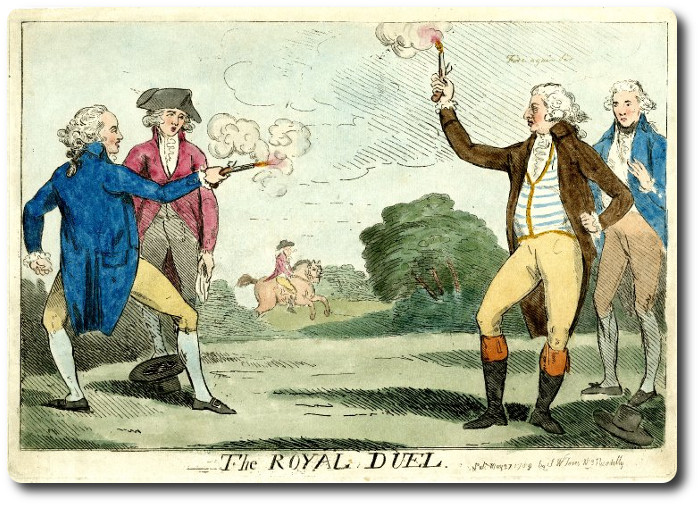

There is an obvious relation between ragging and the petty tyrannies practiced by juvenile despots (and permitted by their teachers) at Eton, Harrow and other schools through which many youths of the upper class pass before entering the army. The imposition of fagging and the birching of sturdy boys who have passed the age of sixteen seem opposed to the development of self-respect, manly spirit and a sense of fair play. If this were not so it would be hard to suggest any explanation of the extraordinarily tame fashion in which young military officers have so often submitted to organized assaults so brutal and disgusting that the victims would have been justified in shooting their tormenters.

Probably no man in the country has acquired a more intimate knowledge of such practices that Dr. Miller Macguire, the noted army coach, who is also a barrister and expert in military law. He has told Mr. Haldane that ragging is primarily an outcome of "the incredible depravity of fashionable public schools and the luxurious and base environment in which the wealthier English people waste their lives." he calls the military code "a piece of low ruffianism" and states that many of the young officers have received no proper education, have no mental curiosity, and "can only talk about sport, games and fashionable women much older and more frivolous than themselves." In support of his assertion as to their ignorance, he quotes reports written by Lord Roberts and generals Hutchinson, Smith-Dorrien and Buller. Further evidence is supplied by Mr. A.C. Benson, a former master at Eton, who states that "the intellectual standard maintained at the English public schools is low"; that it is not tending to become higher; that the indoor life of such places is a series of tedious hours beguiled with billiards, bridge or with anticipations or recollections of open-air amusements; and that unless a boy happened to have a naturally very keen intellectual bent "his interest is not likely to survive in an atmosphere where intellectual things are, to put it frankly, unfashionable."

Posted by regimentalrogue

at 12:01 AM EDT

The London Daily News says that the unsuitability of the present regulation dress of our army for fighting and campaign purposes is held by

The London Daily News says that the unsuitability of the present regulation dress of our army for fighting and campaign purposes is held by

Organization

Organization

One of our most agreeable duties [at the

One of our most agreeable duties [at the

"Let me briefly tell you how the day is passed. Early in the morning, generally at half-past four, there is a scraping at the tent door, and a voice is heard, "Signoir alzate, vi prego, in cafe a pronto," to which a lisping voice responds, "What Thpero, it ith'nt five, thurely?'…'Si, signoir, vbicino a'le cinque,' cries the faithful old idiot (our best servants have been in lunatic asylums), and the British officer is soon up and doing, his coffee is drunk, biscuit and pork are consumed, a wallet is thrown across the shoulder, containing provender for the day, and a flask of rum; the sword is girt on, and away goes out companion to the trenches, there to remain until 6 p.m., leaving us to snooze away until the sun has afforded us a cheering supply of light and heat, when we rise from our bed of blankets, and, having drunk in pure air during the night, rush to breakfast with ravenous appetites.

"Let me briefly tell you how the day is passed. Early in the morning, generally at half-past four, there is a scraping at the tent door, and a voice is heard, "Signoir alzate, vi prego, in cafe a pronto," to which a lisping voice responds, "What Thpero, it ith'nt five, thurely?'…'Si, signoir, vbicino a'le cinque,' cries the faithful old idiot (our best servants have been in lunatic asylums), and the British officer is soon up and doing, his coffee is drunk, biscuit and pork are consumed, a wallet is thrown across the shoulder, containing provender for the day, and a flask of rum; the sword is girt on, and away goes out companion to the trenches, there to remain until 6 p.m., leaving us to snooze away until the sun has afforded us a cheering supply of light and heat, when we rise from our bed of blankets, and, having drunk in pure air during the night, rush to breakfast with ravenous appetites.

London, May 12.—A court-martial is in progress at Dublin against certain officers of the

London, May 12.—A court-martial is in progress at Dublin against certain officers of the  London, 13th February.—The whole absurd story of how the fashionable young bloods of the

London, 13th February.—The whole absurd story of how the fashionable young bloods of the  London, 22nd April.— In conformity with the instructions given by

London, 22nd April.— In conformity with the instructions given by

Reference Officer Retention. Instead of looking for outside influences, the Army needs to look inward. Good units with good leaders retain more soldiers. The same is true for the officer corps. When junior officers have strong, positive leadership, they are more inclined to stay in the Army. When presented with bad leadership, they want out. Talking with peers, most notably in the past 6 months, there seems to be an alarming number of bad leaders out there. Leaders who sugar coat things to higher; leaders who lie; leaders who are immoral; leaders who won't think twice about killing a career over an honest mistake or a difference of opinion; leaders who lead by fear and intimidation; leaders who care more about themselves than their soldiers/officers; leaders who look away at transgressions of others "for the good of the Army". Who wants to work under conditions where they are exposed to bad leadership? Who wants to be in an Army where the people who succeed do not fit the mold of the person you want to be? Who wants to be in a unit where the leadership would not think twice about overworking you or exposing you to unnecessary hardship and/or risk? Who wants to serve in an organization where they are disgraced by the acts of a few? While I can't voice the percentage of bad leaders, what number of examples would indicate that there are too many? I would argue that in the profession of arms, one would be too many. If in an officer's first couple of years in the Army he exposed to bad leaders without any examples/exposure to good leaders, you can bet he will leave. If exposed to an even mix of good and bad, the severity of each and/or the sequence relative to the time of the decision to stay in the army is made, will effect the decision. If exposed to only good leaders, there will still be some who elect to leave the service but at a much lower rate.

Reference Officer Retention. Instead of looking for outside influences, the Army needs to look inward. Good units with good leaders retain more soldiers. The same is true for the officer corps. When junior officers have strong, positive leadership, they are more inclined to stay in the Army. When presented with bad leadership, they want out. Talking with peers, most notably in the past 6 months, there seems to be an alarming number of bad leaders out there. Leaders who sugar coat things to higher; leaders who lie; leaders who are immoral; leaders who won't think twice about killing a career over an honest mistake or a difference of opinion; leaders who lead by fear and intimidation; leaders who care more about themselves than their soldiers/officers; leaders who look away at transgressions of others "for the good of the Army". Who wants to work under conditions where they are exposed to bad leadership? Who wants to be in an Army where the people who succeed do not fit the mold of the person you want to be? Who wants to be in a unit where the leadership would not think twice about overworking you or exposing you to unnecessary hardship and/or risk? Who wants to serve in an organization where they are disgraced by the acts of a few? While I can't voice the percentage of bad leaders, what number of examples would indicate that there are too many? I would argue that in the profession of arms, one would be too many. If in an officer's first couple of years in the Army he exposed to bad leaders without any examples/exposure to good leaders, you can bet he will leave. If exposed to an even mix of good and bad, the severity of each and/or the sequence relative to the time of the decision to stay in the army is made, will effect the decision. If exposed to only good leaders, there will still be some who elect to leave the service but at a much lower rate.

Basic School was a school in fact as well as in name, a halfway house between the campus and the real

Basic School was a school in fact as well as in name, a halfway house between the campus and the real

2. The Profession of Arms is an ancient and honorable one. The Homeric Warriors, the Knights of the Round Table, Jeanne d'Arc are part of our heritage.

2. The Profession of Arms is an ancient and honorable one. The Homeric Warriors, the Knights of the Round Table, Jeanne d'Arc are part of our heritage.

When Bobby came up from

When Bobby came up from

The

The