Writes From Somme of the Big Fight

Topic: CEF

Writes From Somme of the Big Fight

Dawson Daily News, 5 February 1917

Harold Jukes Marshall, assayer of B.N.A. of this city, has received the following interesting letter from his brother, Major W.A.J. Marshall, of the Seventy-second Highlanders, who were recruited at Vancouver, and who have done some of the heavy fighting at the Somme:

Harold Jukes Marshall, assayer of B.N.A. of this city, has received the following interesting letter from his brother, Major W.A.J. Marshall, of the Seventy-second Highlanders, who were recruited at Vancouver, and who have done some of the heavy fighting at the Somme:

"Guernsey, December 6, 1917—When we first went to France, we landed at La Havre, and after two days' wait went on trains to Ypres, where we had a couple of days in the trenches, and then moved on to Kimmelle, where we spent a month and thought the trench life, with the rats and other discomforts, very hard, but find it was nothing compared to where we were going.

"Near to the end of September we moved back to a little place near St. Omer. It was a very hard march of about fifty miles, which we covered in three days.

"There we went into training for the special kind of warfare in use on the Somme, and after a week there were moved down to the well-known Somme.

"On arriving there we were camped first outside Albert, in a sea of mud. The men had tarpaulins and the officers tents. We did not go into action for some time, though. Our work consisted of supplying working parties at night to fig new trenches when advances had been made, and carry up all kinds of material to the men in the trenches.

"This was particularly nasty work, because we were not fighting, but were always under fire and were continually losing men. Even in camp we were not free from shells, as the Boche often dropped a few close to us, and once in the middle of the camp, but no one was hurt.

"After that we went to the trenches to hold them, and, unfortunately, it was a new trench and when it rained the sides fell in and for three days out of seven we stood in mud up to and above our knees. The men we relieved had to dig out and when our men came out they were absolutely all in.

"It is impossible to imagine what it was like, and no matter how well it is told to you, you cannot realize what it was like, but you can think it was bad when I say the man and officers after the trip looked like walking ghosts—thin and weak. The trenches were in such a bad condition that it was hard to get food up to them, and water was scarce, too.

"The next time we went in was for forty-eight hours and the weather conditions were much better. I had then taken command of C Company and my job at that time was to go up and dig a new trench and occupy it, which we did. This had to be done under fire, and until the men had dug down to a depth sufficient to give them some cover we had quite a lively time, and never saw anything like the way they dug. The Boche was about 500 yards away. On the second morning, the thirteenth, I was hit in the arm.

"The day opened with our artillery starting a 'Hymn of Morning Hate,' as we call it, which is nothing but a heavy bombardment lasting about one hour. The Germans came back on our line with the same, as they probably thought we were coming over, and I got a piece of their shell.

"After things had become quiet and breakfast was over I went to the dressing station, and would have gone from there to the hospital only I saw the colonel, who told me we were to go over the top and take the German trench beyond Regina, which we held. So after being dressed I went back to the line and arranged everything for the attack in the afternoon.

"However, about noon it was all called off and we were relieved that night.

"After another rest of about five days we went back for a trips of forty-eight hours at most and had another trench to dig, but we did not come out for six days, the relief being postponed each day. You cannot imagine the strain of sitting in the trench with then Boche pounding you all the time with his artillery. The only thing we could do was a little sniping to help break the monotony, and we got many of his men at this game. The last day we were in it rained and we were over our knees in no time and were all soaked to the skin before we came out.

"That was our last trip on the Somme and after we started away from this area leave opened, and, being the senior married officer outside the colonel, I was first on the list, and very glad to get it.

"I will probably get back about the 15th and spend Christmas in the trench.

"I had my wound examined here yesterday and find the bone was cracked, but will be O K soon.

"I think I have covered most of my trip and all I can add would be horrors, and if you see the Somme pictures you will have a small idea of what goes on there nearly every day. Wishing you both a Merry Christmas and Happy New Year."

Posted by regimentalrogue

at 12:01 AM EDT

Harold Jukes Marshall, assayer of B.N.A. of this city, has received the following interesting letter from his brother,

Harold Jukes Marshall, assayer of B.N.A. of this city, has received the following interesting letter from his brother,

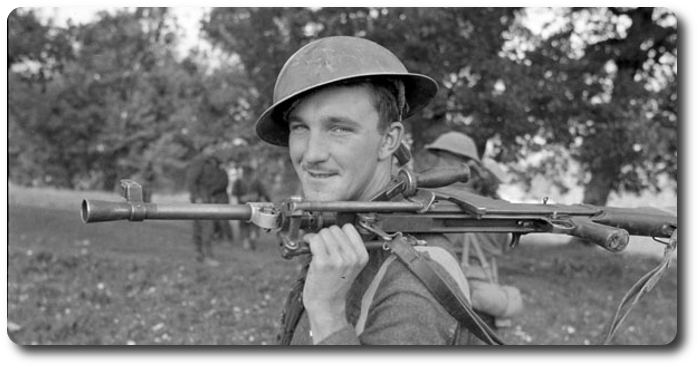

A Canadian infantry division was a large and complex body of men. Commanded by a major-general, its basic war establishment was some 18,376 men. The largest single group of those men were the 8418 infantrymen organized in nine infantry battalions (the eventual infantry battalion establishment was thirty eight officers and 812 men). Each battalion had a support company, and four rifle companies. Each rifle company was made up of a company headquarters and three platoons of one officer (a lieutenant) and thirty-six men. The support company would eventually comprise a carrier platoon, a mortar platoon, a pioneer platoon, and an anti-tank platoon. Three battalions would be joined in an infantry brigade, commanded by a brigadier; an infantry division had three infantry brigades.

A Canadian infantry division was a large and complex body of men. Commanded by a major-general, its basic war establishment was some 18,376 men. The largest single group of those men were the 8418 infantrymen organized in nine infantry battalions (the eventual infantry battalion establishment was thirty eight officers and 812 men). Each battalion had a support company, and four rifle companies. Each rifle company was made up of a company headquarters and three platoons of one officer (a lieutenant) and thirty-six men. The support company would eventually comprise a carrier platoon, a mortar platoon, a pioneer platoon, and an anti-tank platoon. Three battalions would be joined in an infantry brigade, commanded by a brigadier; an infantry division had three infantry brigades.

Every Soldier has a Story: Hercul Bureau

Every Soldier has a Story: Hercul Bureau

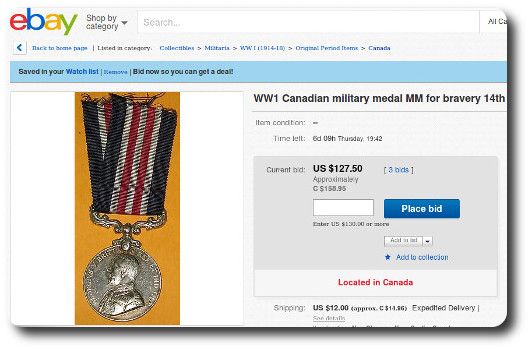

But Hercul's performance was clearly not always such to keep him in the Sergeant Major's crap list. On 7 November, 1917, the entry was made in his service record that he had been awarded the Military medal in the field. Private Hercul Bureau was not just the recipient of the Military Medal, he was actually awarded the Military Medal and Bar, which means he was decorated twice for bravery, each time being the deserving recipient of the Military Medal. The Bar to his Military Medal was recorded in his service record on 26 August 1919, catching up to him long after the end of the War as the backlog of paperwork and recommendations for awards were being cleared away.

But Hercul's performance was clearly not always such to keep him in the Sergeant Major's crap list. On 7 November, 1917, the entry was made in his service record that he had been awarded the Military medal in the field. Private Hercul Bureau was not just the recipient of the Military Medal, he was actually awarded the Military Medal and Bar, which means he was decorated twice for bravery, each time being the deserving recipient of the Military Medal. The Bar to his Military Medal was recorded in his service record on 26 August 1919, catching up to him long after the end of the War as the backlog of paperwork and recommendations for awards were being cleared away.

The law in regard to the Militia being called out in aid of the civil power wil1 be found in the Militia Act, Sections 75-85 inclusive. K.R. (Can.) 848.

The law in regard to the Militia being called out in aid of the civil power wil1 be found in the Militia Act, Sections 75-85 inclusive. K.R. (Can.) 848.

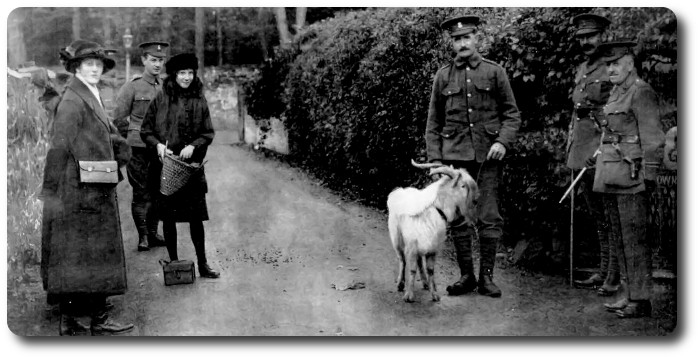

Possibly the most well-known animals of this kind are goats of

Possibly the most well-known animals of this kind are goats of  Rams seem to have some affinity to goats if only in general appearance and the 2nd Bn.

Rams seem to have some affinity to goats if only in general appearance and the 2nd Bn.

"The

"The

1. The designation of the Regiment is "

1. The designation of the Regiment is "