Canadians sink four German warships

Topic: The Field of Battle

A Universal Carrier of The Lake Superior Regiment, Cintheaux, France, 8 August 1944. Photographer: Ken Bell. MIKAN Number: 3396172. From the Library and Archives Canada Faces of the Second World War Collection.

Canadians sink four German warships with fire from tanks and infantry weapons

The Maple Leaf; 10 November, 1944

By: Capt. Jack Golding

Canada's soldiers have been credited with many bizarre accomplishments in their scrapping throughout France, Belgium and Holland but one of the most unique operations to date happened very recently when men of the Lake Superior Regiment and the 28th CAR (British Columbia Regiment) engaged four naval vessels in the little harbor of Zijpe on Duiveland, east of Steenbergen, and sank them with tank and infantry weapons.

They licked the Jerry patrol ships on their own home waters in one of the most lustrous actions f the Canuck fight along the uncomfortable Dutch front. All this happened amid the wild acclaim of a liberated and cooperative Flemish population at St. Phillipsland, where an old world atmosphere of costume and custom made the incident seem like a nebulous tale from Henty, the Arabian Nights or Edgar Allen Poe.

A company of the Lake Superiors with some BCRs had finished their push to Bruges. They had been engaged in infantry work, uncommon to their role, and were assigned the task of moving out the St Phillipsland isthmus to take a look-see.

St Phillipsland they found to be a quaint Dutch village, bubbling with hilarity at liberation.

Here it was learned that German gunboats were across a 1,300 yard stratch of water opposite the tiny town of Sluis a bit farther up the isthmus. So Lieut Buck Wright, Kenora, was sent ahead by Capt Roy Styffe, company commander, Port Arthur.

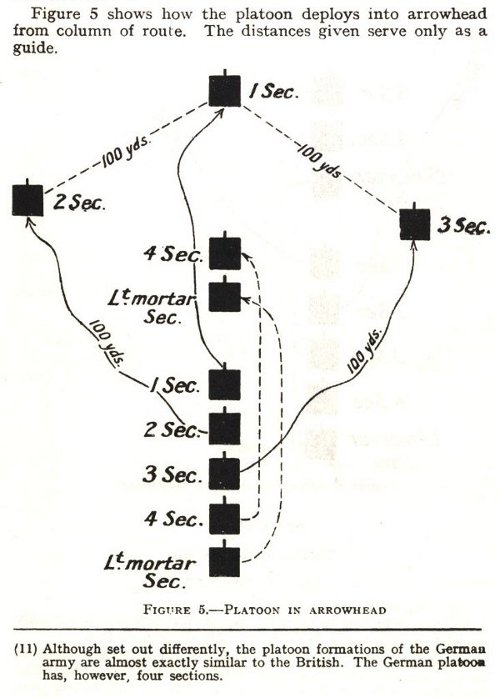

Wright found a water tower at Sluis and clambered up to do a bit of O-pipping. To his amazement he saw men in German naval uniforms walking about blandly, Nazi ensigns flapping and leisurely activity in progress. He couldn't see all the scene for the little harbor was in two parts, divided in the center.

He reported back with the dope but his comrades thought the story a little tall. Finally they checked again and moved up a scout platoon, a troops of tanks, two six pounders and two three inch mortars. There weren't many men involved but the firepower was potent. The balance remained in Phillipsland.

Sgt Curley McLean, Fort William, and Sgt Reg Bullough handled the six pounders and mortars and Lieut Dusty Gopele of the BCR's growled his tanks into position. They estimated ranges and let go!

Plenty of stuff crossed the water to the Jerry navy for five minutes, then reprisal began. They poured it back in a hurry, for each of the four boats there, one like a small corvette and the other three converted landing craft, carried two 88's, two 20 centimeter guns, plenty of machine guns and were manned by 50 to 60 men apiece.

The Canadian regrouped their tanks behind dykes; used indirect fire on corrected ranging and kept the barrels hot for 10 minutes.

Then the enemy stopped suddenly.

All that night the Canadians kept the sky alight with mortar flares for they didn't want the pint-sized flotilla to escape. No move to depart eas in evidence. The boys thought they had gone, however, for they received a civilian report to that effect.

Capt Styffe decided it was time to investigate matter so he, Lieut Bernard Black, Fort William, and Lieut Tommy Henderson, Winnipeg, plus 40 men set sail on their own private invasion in three small boats. One was a cutter, one a fishing schooner and the other a police boat. They needed the latter for there weren't enough Mae Wests to go around.

Capt Styffe had a radio aboard and he kept contact with Wright and Gopele on the front at Sluis. They landed to the left of Zijpe; slipped around toward the back of the harbour under covering fire by Henderson and his men at the beach head and kept their fingers crossed.

On entering the town the first place they struck was the naval commander's billets. Warm food was on the table and there was every evidence of a hurried departure. They ran into four Jerries in the street and relegated them to their forefathers. They thought they saw some masts sticking up at the outer part of the harbor, shielded from view of the force near Sluis.

Black, Cpl M.M. Shaw, Chatham, Ont., and Cpl T.E. Mitchell, Toronto, got a rubber dinghy and paddled out. It was cold and wet and a high November wind whipped the water into a choppy surge. It was true! The three converted landing craft were sunk and the corvette was afire. No-one would believe this. The just had to get proof.

Ensigns as Evidence.

So the intrepid three sailed the bumpy water and grabbed some Nazi ensigns. Then the assault force returned to St Phillipsland with the tale of their success.—and the white hooded Dutch women and their husbands were delighted.

Lieut Blackwas itchy the next day and he persuaded his OC to let him go back again. This time he took Cpl Mitchell, Pte R.A. Cox, Saskatchewan, and Pte L.M. Seeley, Snowden, Sask. What they didn't find wasn't worth finding. Fire had reached the ship's magazine and shrapnel was flying about.

The corvette type craft yielded full length leather suits, silk underwear and champagne. Twenty Germans had been killed and 80 wounded. The rest had flown to the nethermost part of the island. It had been an "Iron Cross" ship with a kill to its credit. The citizens rounded up five Hun sailors and two collaborators.

Another of the patrol vessels had two aircraft to its credit.

Captain's Body Found

At 1,300 yard the Canuck mortars, six pounders and 17 pounders had smacked their targets on the button. The tank fire had sunk the boats. One shell went through four and a half inches of steel and a half inch of concrete on the bridge of the larger vessel to kill the captain. His body was found lying in the wheelhouse with his hands still in his pockets. It was the AF 92.

Prisoners told the Canadians that they, too, had seen them early in the show when neither side knew the other was near. They had reported seeing Allied soldiers but were "pooh poohed" and told they were Nazi paratroopers. They claimed not to like the Nazi regime, but were reported to be well trained men.

The Canadians didn't have a single casualty.

When Capt Styffe received the ship's log, he made the last entry: "Gersunken by Lake Superior Regiment—Canadian Army."

Posted by regimentalrogue

at 12:01 AM EDT

Extracted ftom the Canadian Army Manual of Training; Survival Operations (1961), (Revised May 1962); CAMT 2-91

Extracted ftom the Canadian Army Manual of Training; Survival Operations (1961), (Revised May 1962); CAMT 2-91

The Evolution of Weapons and Warfare,

The Evolution of Weapons and Warfare,  The front gates of Fort Frontenac, Kingston, Ontario,

The front gates of Fort Frontenac, Kingston, Ontario,

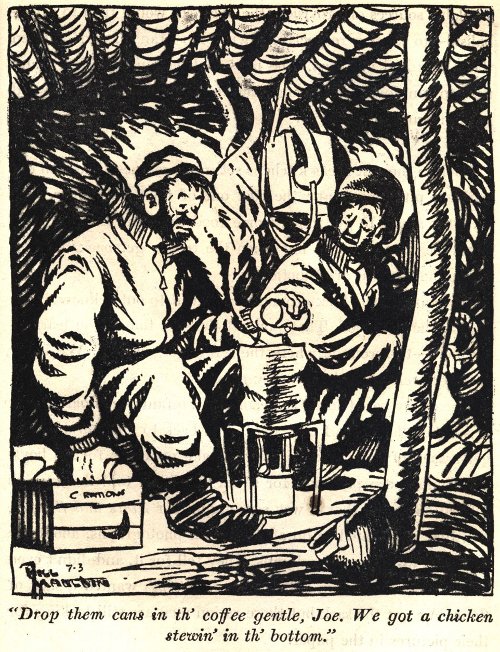

a. The garrison ration is that which the Government prescribes in time of peace for all persons entitled to a ration except under special circumstances when other rations are prescribed. The different items such as meat, fresh vegetables and fruit, beverages, bread, and other articles of food which make up that ration are called "ration components." The number af components and the amount of each required to give a soldier a well-balanced and nourishing daily diet have been carefully determined by food experts. The money value of the ration is figured each month from the wholesale costs of food to the Government, and your organization mess account is credited with the total amount required to feed a1l the men in your unit. The meals served by your organization mess sergeant in time of peace, and while Your organization is in a post, camp, or cantonment, will usually be prepared from the components of the garrison ration. After the mess sergeant has made up his menus he will buy the various articles of food required from the money which the Government has credited to your organization mess account. Some of these items he may buy from the quartermaster commissary. Others he may buy from local markets or farmers, in order to take advantage of certain foods in season or because the commissary may not have them in stock. Any savings which he makes are called "ration savings'' and become part of your unit mess fund, to be expended by your organization commander on extras for the mess on holidays or other special occasions.

a. The garrison ration is that which the Government prescribes in time of peace for all persons entitled to a ration except under special circumstances when other rations are prescribed. The different items such as meat, fresh vegetables and fruit, beverages, bread, and other articles of food which make up that ration are called "ration components." The number af components and the amount of each required to give a soldier a well-balanced and nourishing daily diet have been carefully determined by food experts. The money value of the ration is figured each month from the wholesale costs of food to the Government, and your organization mess account is credited with the total amount required to feed a1l the men in your unit. The meals served by your organization mess sergeant in time of peace, and while Your organization is in a post, camp, or cantonment, will usually be prepared from the components of the garrison ration. After the mess sergeant has made up his menus he will buy the various articles of food required from the money which the Government has credited to your organization mess account. Some of these items he may buy from the quartermaster commissary. Others he may buy from local markets or farmers, in order to take advantage of certain foods in season or because the commissary may not have them in stock. Any savings which he makes are called "ration savings'' and become part of your unit mess fund, to be expended by your organization commander on extras for the mess on holidays or other special occasions.