Forfeiture of Medals

Topic: Medals

Once a soldier has earned an honour or award, whether that be a decoration for valour or a service medal for service abroad of long service, it is perceived that there will always be an attendant respect for his accomplishments. But the challenge of what to do with a soldier whose later actions undermine that desired perception of respect and honour has long confronted authorities. In recent years in Canada, the

medals awarded to Col Russell Williams were taken back by the Canadian military after his conviction for murder. This is not a new practice, the following extract from General Orders shows that it is a long established practice in the British Empire and was formally recognized by Canada well over a century ago.

Militia General Orders

Ottawa, 15th June, 1888

General Order, No. 3

Forfeiture and Restoration of Medals

The following Imperial Regulations apply in all cases where medals have been granted to miltiamen in Canada:—

The following Imperial Regulations apply in all cases where medals have been granted to miltiamen in Canada:—

Paragraphs 982, 983 and 984, Royal Warrant, 1887, Part 1, section 6, Rewards, etc.:

982. Every soldier who is found guilty by a Court Martial of the following offences: desertion, fraudulent enlistment, any offence under section 17 or 18 Army Act, 1881, and every soldier who is sentenced by a Court Martial to penal servitude, or to be discharged with ignominy; shall forfeit all Medals and Decorations (other than the Victoria Cross, which is dealt with under special regulations) of which he may be in possession, or to which he may have been entitled, together with any annuity or Gratuity thereto appertaining.

983. Every soldier show:—

(a) is liable on confession of desertion or fraudulent enlistment, but whose trial has been dispensed with;

(b) is discharged in consequence of incorrigible and worthless character; or expressly on account of misconduct; or on conviction by the Civil Power; or on being sentenced to penal servitude, or for giving a false answer on attestation;

(c) is found guilty by a Civil Court of an offence which, if tried by Court Martial, would be cognizable under section 17 or section 18, Army Act; or is sentenced by a Civil Court to a punishment exceeding six months imprisonment;

Shall forfeit all Medals (other than the Victoria Cross, which is dealt with under special regulations) granted to him subsequently to the date of Our Warrant of 25th June, 1881, together with the annuity or gratuity, if any, thereto appertaining.

984. Any General or District Court Martial may, in addition to or withour any other punishment, sentence any offender to forfeit any Medal or Decoration (other than the Victoria Cross, which is dealt with under special regulations), together with the annuity or gratuity, if any, thereto appertaining which may have been granted to him; but no such forfeiture shall be awarded by the Court Martial when the offence is such that the condition does of itself entail a forfeiture under Articles 982 and 983.

Paragraph 12, Section–XX–Medals—The Queen's Regulations and Orders for the Army, 1885:—

12. When Medals are forfeited they are to be transmitted to the Adjutant General for disposal. The same course is to be followed in case of Medals, which may have been recovered after a soldier has been convicted of making away with them. Letters containing Medals when forwarded through the post, are to be registered.

Paragraphs 17 and 18 of the Army Act, 1881

The following text of paragraphs 17 and 18 of the Army Act, 1881 are taken from the 1907 edition of the Manual of Military Law.

17. Every person subject to military law who commits any of the following offences; that is to say,

Being charged with or concerned in the care or distribution of any public or regimental money or goods, steals, fraudulently misapplies, or embezzles the same, or connives at the stealing, fraudulent misapplication, or embezzlement thereof, or wilfully damages any such goods on conviction by court-martial be liable to suffer penal servitude, or such less punishment as is in this Act mentioned.

18. Every soldier who commits any of the following offences; that is to say.

(1.) Malingers, or feigns or produces disease or infirmity or

(2.) Wilfully maims or injures himself or any other soldier, whether at the instance of such other soldier or not, with intent thereby to render himself or such other soldier unfit for service, or causes himself to be maimed or injured by any person, with intent thereby to render himself unfit for service; or

(3.) Is wilfully guilty of any misconduct, or wilfully disobeys, whether in hospital or otherwise, any orders, by means of which misconduct or disobedience he produces or aggravates disease or infirmity, or delays its cure; or

(4.) Steals or or embezzles or receives, knowing them to be stolen or embezzled any money or goods the property of a comrade or of an officer, or any money or goods belonging to any regimental mess or band, or to any regimental institution, any public money or goods; or

(5.) Is guilty of any other offence of a fraudulent nature not before in this Act particularly specified, or of any other disgraceful conduct of a cruel, indecent, or unnatural kind,

shall on conviction by court-martial be liable to suffer imprisonment, or such less punishment as is in this Act mentioned.

Special Provisions for the Victoria Cross

Special Provisions for the Victoria Cross

The special provisions for the Victoria Cross were provided in the Fifteenth article of the original Warrant for the award, published in the London Gazette on 5 February 1856:

Fifteenthly. In order to make such additional provision as shall effectually preserve pure this most honourable distinction, it is ordained, that if any person on whom such distinction shall be conferred, be convicted of treason, cowardice, felony, or of any infamous crime, or if he be accused of any such offence and doth not after a reasonable time surrender himself to be tried for the same, his name shall forthwith be erased from the registry of individuals upon whom the said Decoration shall have been conferred by an especial Warrant under Our Royal Sign Manual, and the pension conferred under rule fourteen, shall cease and determine from the date of such Warrant. It is hereby further declared that We, Our Heirs and Successors, shall be the sole judges of the circumstance demanding such expulsion; moreover, We shall at all times have power to restore such persons as may at any time have been expelled, both to the enjoyment of the Decoration and Pension.

Her Majesty Queen Victoria reserved the right to determine if any soldier should be required to forfeit the award for valour fashioned in her name.

Posted by regimentalrogue

at 12:01 AM EDT

In Australian there is a gentleman, Lieutenant Colonel Glyn Llanwarne, OAM, who is also a "medal rescuer." LtCol Llanwarne's commendable approach to this activity is best describe in his own words:

In Australian there is a gentleman, Lieutenant Colonel Glyn Llanwarne, OAM, who is also a "medal rescuer." LtCol Llanwarne's commendable approach to this activity is best describe in his own words:

On a popular

On a popular  There were hundreds of medals to Canadians on ebay that month. Why that particular medal. The soldier's unit is one that evokes sentimental feelings, a book has been written about them, and doing good for a worthy cause never falls short of gaining support. The rescuer and the media milked that angle for all it was worth and let momentum take its course. As soon as the media spotlight turns on a particular auction, there's no guessing where it will go. Other medals to soldiers of that unit have sold since at market values without the media attention. Perhaps it was a well-intentioned plan, but the way it was executed in the public eye, with emotional media support derailed any good intentions in the result. Yet somehow we always seem to see the "rescuer" lauded, even when a charitable organization has to raise

There were hundreds of medals to Canadians on ebay that month. Why that particular medal. The soldier's unit is one that evokes sentimental feelings, a book has been written about them, and doing good for a worthy cause never falls short of gaining support. The rescuer and the media milked that angle for all it was worth and let momentum take its course. As soon as the media spotlight turns on a particular auction, there's no guessing where it will go. Other medals to soldiers of that unit have sold since at market values without the media attention. Perhaps it was a well-intentioned plan, but the way it was executed in the public eye, with emotional media support derailed any good intentions in the result. Yet somehow we always seem to see the "rescuer" lauded, even when a charitable organization has to raise

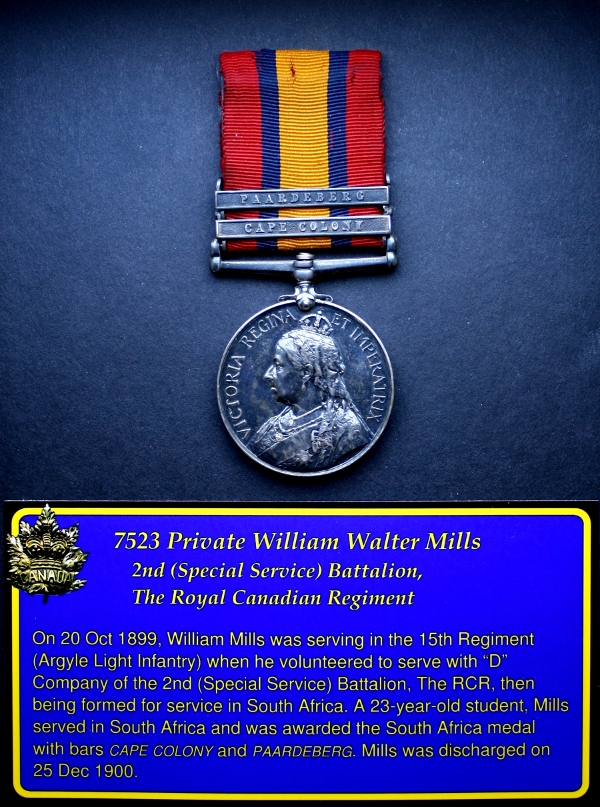

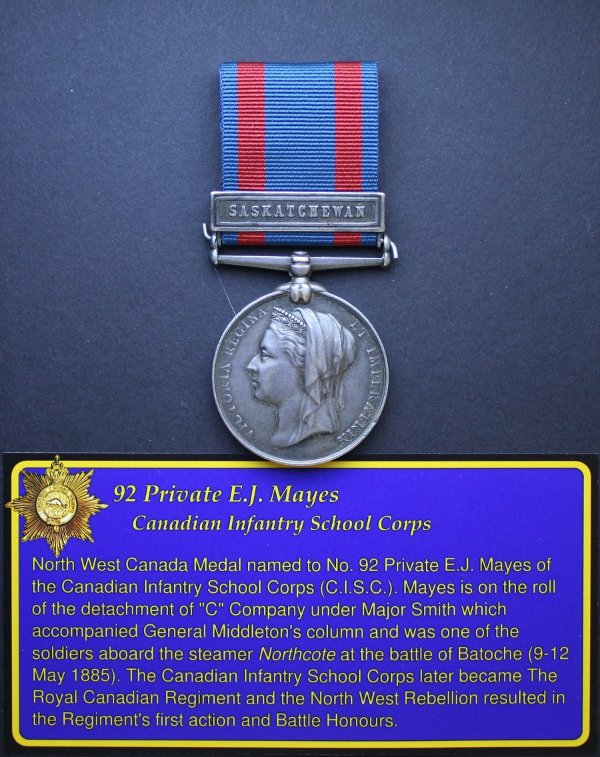

As a dedicated collector to a very narrow theme (medals to soldiers of a single regiment with a main focus on one war), I simply don't have time to be available in multiple places in case a family member brings a medal in for sale, or to watch dozens of militaria shows and auctions, or to advertise my specific desires in hopes that I can find matching first order sellers. Instead, I must rely upon, and I welcome the participation of, dealers who do all of those things. They deal in medals with a generalist intent, resorting the items they gather and enabling me to pick and choose the single items that match my theme, as they similarly provide for the collecting desires of hundreds or thousands of other theme based collectors. Without the great support of dealers, some of who become friends and will contact specific collectors directly when they receive something they know fits a unique collection, I, for one, could never have amassed the modest collection I have and display. The dealers, those so-called "profiteers," are an essential part of this collective endeavour called medal collecting that leads to the preservation and research of individual medals by collectors.

As a dedicated collector to a very narrow theme (medals to soldiers of a single regiment with a main focus on one war), I simply don't have time to be available in multiple places in case a family member brings a medal in for sale, or to watch dozens of militaria shows and auctions, or to advertise my specific desires in hopes that I can find matching first order sellers. Instead, I must rely upon, and I welcome the participation of, dealers who do all of those things. They deal in medals with a generalist intent, resorting the items they gather and enabling me to pick and choose the single items that match my theme, as they similarly provide for the collecting desires of hundreds or thousands of other theme based collectors. Without the great support of dealers, some of who become friends and will contact specific collectors directly when they receive something they know fits a unique collection, I, for one, could never have amassed the modest collection I have and display. The dealers, those so-called "profiteers," are an essential part of this collective endeavour called medal collecting that leads to the preservation and research of individual medals by collectors. There always seems to be someone ready to denigrate the collector of military medals. "Profiting off their honour," they'll say, or "dishonouring the heroes." Sometimes, it's snide remarks inferring that the medals held by collectors must have been received via nefarious means, either stolen from families or swindled from poor widows. Collectors have even been called the "

There always seems to be someone ready to denigrate the collector of military medals. "Profiting off their honour," they'll say, or "dishonouring the heroes." Sometimes, it's snide remarks inferring that the medals held by collectors must have been received via nefarious means, either stolen from families or swindled from poor widows. Collectors have even been called the " "Ban the sale of medals!" is an occasionally heard rally cry, one sometimes taken up by politicians seeking favour with constituents who might support such a measure. But this argument also is seldom fully developed; emotional cries for change seldom are. Should medals cease to be personal property, returned to the Crown on the death of the recipient? Would that not also prevent them passing to direct descendants? Or should families be required to register and retain them, releasing them only back to the Government to be held in an approved repository like a museum? How would we track such things, with a medal registry? What would we do with current collectors, seize their collections or grandfather them without allowance to resell ever?

"Ban the sale of medals!" is an occasionally heard rally cry, one sometimes taken up by politicians seeking favour with constituents who might support such a measure. But this argument also is seldom fully developed; emotional cries for change seldom are. Should medals cease to be personal property, returned to the Crown on the death of the recipient? Would that not also prevent them passing to direct descendants? Or should families be required to register and retain them, releasing them only back to the Government to be held in an approved repository like a museum? How would we track such things, with a medal registry? What would we do with current collectors, seize their collections or grandfather them without allowance to resell ever?  While some collectors may hoard and keep secret their collections and the research they have gathered, often it is because they have found that tactic protects them from the very accusations identified above. But in this increasingly connected world, more collectors are speaking out and sharing the knowledge they have about individual recipients, about the units and battles they have researched, and about the techniques they use both to find information and to preserve and display their collections.

While some collectors may hoard and keep secret their collections and the research they have gathered, often it is because they have found that tactic protects them from the very accusations identified above. But in this increasingly connected world, more collectors are speaking out and sharing the knowledge they have about individual recipients, about the units and battles they have researched, and about the techniques they use both to find information and to preserve and display their collections.

The

The

Militia General Orders

Militia General Orders

For guidance on wearing of medals and ribbons, see the following guide:

For guidance on wearing of medals and ribbons, see the following guide:

It was during the first Fenian raids in 1866, that the only Victoria Cross to be awarded for actions in Canada was granted. This award, for an act of gallantry not in the presence of the enemy (which was allowed by the terms and conditions for the VC for a brief period) was earned by

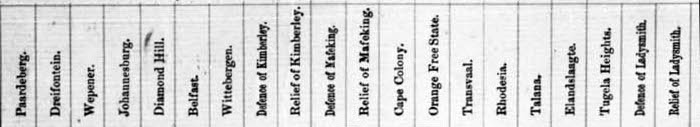

It was during the first Fenian raids in 1866, that the only Victoria Cross to be awarded for actions in Canada was granted. This award, for an act of gallantry not in the presence of the enemy (which was allowed by the terms and conditions for the VC for a brief period) was earned by  From the excellent British service medals reference "

From the excellent British service medals reference " The following Imperial Regulations apply in all cases where medals have been granted to miltiamen in Canada:—

The following Imperial Regulations apply in all cases where medals have been granted to miltiamen in Canada:— Special Provisions for the Victoria Cross

Special Provisions for the Victoria Cross

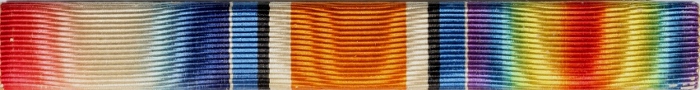

The first medal that many Canadian soldiers might have been eligible to receive for their First World War service was the

The first medal that many Canadian soldiers might have been eligible to receive for their First World War service was the