At a time when the base rates of pay for the Permanent Force infantry sergeants, corporals and privates were $1.00, $0.80, and $0.50, respectively, the opportunities to be appointed to work with extra duty pay was not to be overlooked. Men with appropriate civilian skills who decided to enlist in The Royal Canadian Regiment (or other Permanent Force units), or who achieved the necessary certificates in military training, could supplement their pay well with available extra duty pay. The 1906 regulations regarding Extra Duty Pay show the range of duties which might be available to an N.C.O. or man and the daily rates (i.e., p.d. – per diem) he would be paid in addition to his regular pay.

Canadian Militia

Regulations Respecting Pay and Allowances

Canada Gazette; Ottawa, Saturday, May 4, 1906

Extra Duty Pay

126. Soldiers temporarily performing the duties or acting in the situations specified in paragraphs 128 to 144 shall be granted in addition to ordinary regimental pay, extra duty pay at the rates laid down in those paragraphs.

127. Extra pay shall not be issued to a N.C.O. or man in receipt of engineer pay, corps pay or working pay except as otherwise provided in these regulations, nor shall two rates of extra duty pay be drawn unless specifically authorized by the Minister in Militia Council.

128. N.C.O, and men acting as pay-sergeants or accountants:—

- For an establishment of eighty rank and file.

- If above rank of corporal – $0.25 p.d.

- If corporal or below that rank – 0.40 p.d.

- For an establishment less than eighty rank and file and over twenty-five.

- If above rank of corporal – $0.15 p.d.

- If corporal or below that rank – 0.25 p.d.

- For an establishment of over nine and less than twenty-six – $0.10 p.d.

129. The N.C.O. or man keeping the accounts of special bodies or detachments of troops shall be paid the rates according to the establishment as above.

130. The non-commissioned officers and men acting as provost sergeants, orderly room clerks, sergeant trumpeters and sergeant drummers. – $1.10 p.d.

131. The non-commissioned officers and men acting as riding instructors, rough riders, or instructor in trumpeting. – $0.10 p.d.

132. Carpenters, painters, plumbers, and other artificers when employed as such at infantry and cavalry depots for each working day of seven hours. – $0.25 p.d.

133. Pioneers, whose duty is the care of wash houses and latrines. – $0.20 p.d.

(a) One painter or plumber for the performance for necessary painting and plumbing, is allowed for each company of the Royal Canadian Regiment.

(b) The hours during which work shall be performed are detailed in orders by the officer commanding at each station, and the acting quartermaster shall be required to certify to the number of working days each month for which extra pay is demanded.

134. The N.C.O. and men doing duty as garrison police:—

- If of the rank of sergeant. – $0.25 p.d.

- If of the rank of corporal. – $0.20 p.d.

- If of the rank of private. – $0.15 p.d.

135. The N.C.O. and men doing duty as assistant prison warders:—

- If of the rank of sergeant. – $0.30 p.d.

- If of the rank of corporal. – $0.25 p.d.

- If of the rank of private. – $0.20 p.d.

136. The N.C.O. and men doing duty as assistant gymnastic instructors. – $0.25 p.d.

137. The N.C.O. and men doing duty as telephonists, according to the amount of work, from 5¢ to $0.20 p.d.

138. Extra instructors when absolutely required in large course of instruction at the Royal Schools. – $0.25 p.d.

139. The N.C.O. and men who are thoroughly qualified to instruct drill and musketry according to the arm of the service to which they belong and are capable of imparting the instruction in both French and English. In addition to any other pay:—

- First class instructors. – $0.20 p.d.

- Second class instructors. – $0.10 p.d.

(a) The syllabus and dates of examination shall be published from time to time in Militia Orders.

140. The N.C.O. and men employed as assistant instructors in signalling for corps of Active Militia, while so employed:—

- Holding Grade “A” certificate. – $0.50 p.d.

- Holding Grade “B” certificate. – $0.40 p.d.

(a) Of the staff of assistant instructors in signalling in each unit of the Permanent Force, the best five of the rank and file may be classified as paid signallers and receive throughout the year. – $0.10 p.d.

(b) No signaller shall be qualified for the above extra pay unless re-examined every year and in possession of an assistant instructor's or grade “A” certificate.

141. N.C.O.'s performing the duties of other N.C.O.'s of higher grade undergoing a long course of instruction in gunnery. – $0.10 p.d.

142. The N.C.O. or man employed to attend fires or a furnace:—

- For the period so employed. – $0.20 p.d.

- After two years service if found thoroughly efficient and attentive. – $0.30 p.d.

143. The N.C.O. or man whose duty it is to attend to a lawn:—

- For the days so employed. – $0.20 p.d.

Band Pay

144. The following rates of band pay may be drawn in addition to ordinary regimental pay:—

- Bandmaster. – $1.50 p.d.

- Band sergeant. – $0.25 p.d.

- Band corporal. – $0.15 p.d.

- Bandsman. – $0.10 p.d.

With two grease boxes, pole draught, M.D. No. 1; two

With two grease boxes, pole draught, M.D. No. 1; two

For most conspicuous bravery on 15th June, 1915, during the action at Givenchy. Lt. Campbell took two machine-guns over the parapet, arrived at the German first line with one gun, and maintained his position there, under very heavy rifle, machine-gun and bomb fire, notwithstanding the fact that almost the whole of his detachment had then been killed or wounded. When our supply of bombs had become exhausted, this officer advanced his gun still further to an exposed position, and, by firing about 1,000 rounds, succeeded in holding back the enemy's counter-attack. This very gallant officer was subsequently wounded, and has since died.

For most conspicuous bravery on 15th June, 1915, during the action at Givenchy. Lt. Campbell took two machine-guns over the parapet, arrived at the German first line with one gun, and maintained his position there, under very heavy rifle, machine-gun and bomb fire, notwithstanding the fact that almost the whole of his detachment had then been killed or wounded. When our supply of bombs had become exhausted, this officer advanced his gun still further to an exposed position, and, by firing about 1,000 rounds, succeeded in holding back the enemy's counter-attack. This very gallant officer was subsequently wounded, and has since died. Captain F. W. Campbell. – A second wave of Canadians now surged across No Man's Land, and with it went a machine-gun officer. Lieutenant (acting-Captain) Campbell, with two guns and their crews.

Captain F. W. Campbell. – A second wave of Canadians now surged across No Man's Land, and with it went a machine-gun officer. Lieutenant (acting-Captain) Campbell, with two guns and their crews.  He went at once to Valcartier and was accepted for service as Lieutenant in the 1st (Western Ontario) Battalion. He sailed with the First Canadian Contingent on September 24th, 1914, and reached France in February, 1915. His Battalion took part in the awful fighting at

He went at once to Valcartier and was accepted for service as Lieutenant in the 1st (Western Ontario) Battalion. He sailed with the First Canadian Contingent on September 24th, 1914, and reached France in February, 1915. His Battalion took part in the awful fighting at

Army Act – Discipline (Crimes and Punishments)

Army Act – Discipline (Crimes and Punishments)

The RCR began in 1883 as the

The RCR began in 1883 as the  The PPCLI, in comparison, have taken a very different path with regard to their origins and reputation. They were created in Ottawa in 1914, formed by the targeted recruitment of ex-British Army soldiers, many of whom had seen active service in the Imperial Army. In fact, the regimental history (Williams, pg. 7) states that the first recruiting posters advertised that "Preference will be given to ex-regulars of the Canadian or Imperial Forces; or men who saw service in South Africa." From that beginning, the PPCLI saw themselves as a very British regiment. They started their service in France during the First World War in the

The PPCLI, in comparison, have taken a very different path with regard to their origins and reputation. They were created in Ottawa in 1914, formed by the targeted recruitment of ex-British Army soldiers, many of whom had seen active service in the Imperial Army. In fact, the regimental history (Williams, pg. 7) states that the first recruiting posters advertised that "Preference will be given to ex-regulars of the Canadian or Imperial Forces; or men who saw service in South Africa." From that beginning, the PPCLI saw themselves as a very British regiment. They started their service in France during the First World War in the

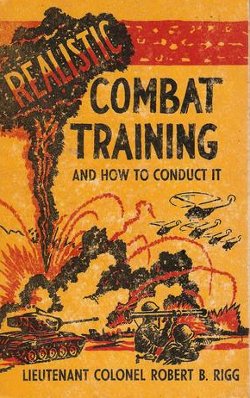

By Robert B. Rigg, Lieutenant Colonel, U.S. Army; Military Service Publishing Company, 1955.

By Robert B. Rigg, Lieutenant Colonel, U.S. Army; Military Service Publishing Company, 1955.

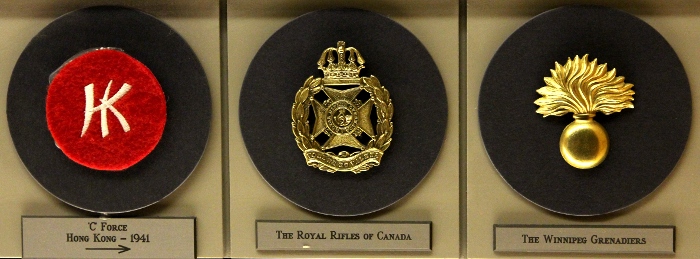

Brigadier John Kelburne Lawson

Brigadier John Kelburne Lawson William James Home, M.C.

William James Home, M.C. On 8 July 1940, the Royal Rifles of Canada (Quebec City) and the 7/XIth Hussars (Richmond) received authorization to mobilize as the 1st Battalion of the Royal Rifles of Canada. The first Commanding Officer was Lt. Colonel William James Home, M.C., E.D. The unit arrived in Hong Kong on 16 November 1941. On 8 December, Japanese forces attacked the British colony. Following ten days of continuous air and artillery bombardment, Japanese troops landed on the island during the night of 18-19 December. Despite a heroic battle to defend the island, the garrison surrendered on 25 December 1941. During the fighting, Lieutenant-Colonel W.J. Home, the commanding officer of the Royal Rifles, became the senior Canadian officer after the death of Brigadier Lawson.

On 8 July 1940, the Royal Rifles of Canada (Quebec City) and the 7/XIth Hussars (Richmond) received authorization to mobilize as the 1st Battalion of the Royal Rifles of Canada. The first Commanding Officer was Lt. Colonel William James Home, M.C., E.D. The unit arrived in Hong Kong on 16 November 1941. On 8 December, Japanese forces attacked the British colony. Following ten days of continuous air and artillery bombardment, Japanese troops landed on the island during the night of 18-19 December. Despite a heroic battle to defend the island, the garrison surrendered on 25 December 1941. During the fighting, Lieutenant-Colonel W.J. Home, the commanding officer of the Royal Rifles, became the senior Canadian officer after the death of Brigadier Lawson.

Journal of the Royal United Service Institution

Journal of the Royal United Service Institution

The mess tin ration or 48-hour ration provides subsistence for the first 48 hours after landing.

The mess tin ration or 48-hour ration provides subsistence for the first 48 hours after landing.

The 7th Fusiliers, which became the Canadian Fusiliers (City of London Regiment) (M.G.), was amalgamated with

The 7th Fusiliers, which became the Canadian Fusiliers (City of London Regiment) (M.G.), was amalgamated with