The Victoria Cross for Heroes Only (1900)

Topic: Medals

The Victoria Cross for Heroes Only (1900)

How the Most Coveted Decoration in England is Won and How it is Bestowed

The Deseret News, Salt Lake City, Utah, 26 January 1900

By Curtis Brown in the St. Louis Globe*#8211;Democrat.

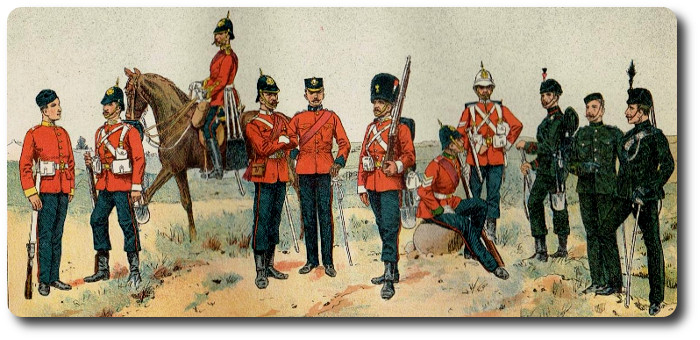

London, Jan. 11.—Lord Roberts of Kandahar, who will arrive at the Cape in a few days to take charge of the biggest British army that ever took the field, is a little man, as everyone knows, and there is not much room left on his coat for additional medals. You can see that for yourself by studying the accompanying picture of him, taken only a few weeks ago. But of all the honors betokened there, and all the others which a genuinely fond public has given him and will shower upon him later if he fulfils their hopes in the Transvaal, the simplest, the least expensive intrinsically, and by far the most democratic, is the one for which, if necessary, you may be sure he would sacrifice all others.

London, Jan. 11.—Lord Roberts of Kandahar, who will arrive at the Cape in a few days to take charge of the biggest British army that ever took the field, is a little man, as everyone knows, and there is not much room left on his coat for additional medals. You can see that for yourself by studying the accompanying picture of him, taken only a few weeks ago. But of all the honors betokened there, and all the others which a genuinely fond public has given him and will shower upon him later if he fulfils their hopes in the Transvaal, the simplest, the least expensive intrinsically, and by far the most democratic, is the one for which, if necessary, you may be sure he would sacrifice all others.

It is the Victoria Cross, the first in the row upon his breast.

Some of the humblest men, socially and financially, in the empire have decorations just like it. But general and private, white man and black, each had the proudest moment of his life when that little bronze cross was laid upon his breast. And Lord Roberts, sailing away to fight on the field where his only son had just been slain, probably was supported in his sense of loss by the consensus of opinion that the action in which the young man lost his life would would have won for him also the Victoria Cross if he had lived.

Lord Roberts won his V.C. in the Indian Mutiny, when only a lieutenant, forty-one years ago, in the course of an action that was unpleasant enough to be named Khodagunge. While the fighting was going on, he saw two of the enemy—Sepoys—making off with the British colors. He was on horseback, and started after them, when they turned on him and aimed their muskets at him. One missed him, the other's gun missed fire, and by that time he was on them, slashing away with his sword. He killed one. The other took to his heels, and the standard was safe. Only a few minutes before the lieutenant had saved the life of one of his men by cutting down a Sepoy who was about to kill him with a bayonet.

Lord Roberts wears nine decorations on his breast on dress occasions, as the illustration shows, and how many more he may have no one feels sure; even the religiously exact army list contents itself with naming five, and then says, breathlessly, "etc., etc."

In the picture one sees the general's six medals in a row, and three others beneath them. Of the medals, following from left to right, the first is the Victoria Cross; the second, the India Mutiny decoration, with three bars, one for Delhi, one for Lucknow, and one for the relief of Lucknow; the third is the Indian medal for 1854, with three claps for Burmah, Umbeylah and Looshai, meaning that this officer has distinguished himself afresh in each of these; the fourth is the Abyssinian medal; the fifth, the Afghan, and the sixth that of Kabul-Kandahar, in recognition of his remarkable march and victorious battle with Ayub Khan. The large decorations beneath are orders—two above and one below. Those above again from left to right, are the Order of the Bath and the Star of India, that below, the Order of the Indian Empire.

Gen. Sir Redvers Buller is another Victoria Cross man. His decoration was granted to him for saving three lives in a retreat after a battle with the Zulus. He was then a captain and a brevet lieutenant colonel. The Zulus were pressing the British troops hard, when an officer's horse was killed and its rider left in fearful danger. Buller galloped back, took the officer up behind him and carried him to a place of safety. Returning, he found a young lieutenant in precisely the same fix, and he did the trick over again. When he got back a trooper's animal had just fallen, exhausted, and for a third time Buller's horse carried a double load, and Buller exposed himself to the enemy to save a comrade although the Zulus were not a hundred yards away.

Sir George White, so long "bottled up" in Ladysmith, won the Victoria Cross under Lord Roberts in Afghanistan, by charging a fortified hill and taking it, backed by only a few men, at this time he was only a major in the famous Gordon Highlanders. They advanced under a racking fire, and on reaching the top of the slope found themselves outnumbered ten to one. Quick as a wink White grabbed a rifle from one of his men and shot the Afghan chief. His followers became demoralized, and the Gordons routed them. Later in the same campaign, on the march to Kandahar Roberts named White a second time in his despatches for having rushed on ahead of his men and captured a gun. He ended by succeeding his superior officer in becoming commander-in-chief in India.

I asked the officer in charge of the medal branch of the war office how a Victoria Cross was obtained after it had been won.

"Why, there isn't as much red tape about it as you would fancy," he said. "The action as a reward for which the cross is given must be performed 'in the presence of the enemy,' and it is desirable that the superior officer of the man who distinguishes himself should have witnessed it. It happens sometimes, however, that no officer is present, and in a case like that the candidate must prove by his companions that he really did do what he asserts that he did. When his immediate superior is satisfied that he ought to be rewarded he writes an account of the business and hands it to the officer in command of the forces and he indorses the papers and sends them on to the war office. Here they are laid before Lord Wolseley, the commander-in-chief, who passes upon them and decides to which applicants the cross shall be given.

"Of course, the cross goes most often to a soldier, sailor or marine, and when it happens that the fortunate man is in England he receives hi medal from the hand of the Queen herself. If he is in the field, however, or on ship board, he receives his decoration from the general or admiral in chief command on the semi-annual inspection day and in the presence of the men who were at the scene of the exploit."

"Then the men who have done brave things do apply personally?"

"Certainly they do. That is in keeping with the spirit of the warrant which the queen first issued in 1856, and which says that he majesty desires that the new decoration should be 'highly prized and eagerly sought after.' In that warrant she said that as the third class Order of the Bath was limited to officers in the higher branches of the service, and as no way then existed to reward heroes adequately for meritorious actions—for army medals of the ordinary kind are given only for long service and exceptional conduct—the Victoria Cross was instituted.

"Sometimes it has happened that several men have done a deed deserving of the cross, without any one of them having distinguished himself above his comrades. In that case the several officers meet and select one officer to be decorated; the non-commissioned officer to be decorated, and the soldiers, marines or seamen also gather an appoint two of their number to receive the crosses.

"Besides the ceremony of presentation in the presence of his comrades," he went on, "the Victoria Cross man has his name mentioned in a general order from the war office, with the particulars of his heroism, and his name also appears in the London Gazette, likewise with an account of what he did, and the original papers are kept sacredly forever afterward. That register is probably the most democratic roll in Great Britain, for upon it the names of nobles and highly placed officers precede and follow those of lowly privates and drummer boys, the one as much honored as the other.

"There have been erasures from that roll, but they can only be made by direct order of the queen, who decides personally all cases where charges are made against V.C. men. Treason, cowardice, felony or other infamous crime are the causes for which a former hero can lose his place in the register. The queen says in her warrant: "We, our heirs and successors shall be the judges of expulsion or restoration."

"Winning a Victoria Cross means a pension of $50 a year from the date of the act for which the cross is bestowed. Then, in cases where the holders of the cross become deserving of it once more, a clasp is added, and each clasp means an increase of $20 a year in the pension. Of course, dishonorable conduct on the part of a V.C. man deprives him of his pension, as well as his place on the register."

The number of crosses bestowed is kept down by a strict observance of the specification which the queen made in her original warrant in 1856, and made emphatic by another in 1881, that the cross should be given not on account of "rank, long service, nor wounds, nor any other service, circumstance or condition save the merit of conspicuous bravery." Politics, said the officer, never is allowed to play a part in the matter.

The queen arranged for the establishment of the cross in 1856, the nineteenth year of her reign, and signified in another royal warrant in 1867 that crosses would be distributed to officers and men who had distinguished themselves in the insurgent wars in New Zealand. In 1857 a second royal warrant had made members of the East India service eligible, and in 1881 came a third warrant, making stronger the phrase "conspicuous bravery," and stating that the warrant was issued as "some doubts had arisen" as to the exact qualification for the cross.

Although no official statement has been made on the subject, it is fair to assume that Lord Wolseley has already decided on a few, at least, of the V.C. winners of the Transvaal war. Winston Churchill has been declared by the public to be deserving of one for his efforts in behalf of the wounded when the armored train was attacked. Trumpeter Sherlock, the boy who shot three Boers with a revolver, and whose example every English boy is dying to emulate—some of them having run away from school with that project in mind—has established a clear claim to one.

More people than he himself will be disappointed if the "bugler boy of Elandslaagte" is not made a V.C. the story of his deed has travelled faster than his name, but he is true to the type of Napoleon's drummer boy who "didn't know how to beat a retreat." Attached to the Gordon Highlanders, who seem always to be prowling around when there is any storming of heights to be done, be it in Europe, Asia or Africa, he and they mounted the slope—at the crest of which the Boers had their stronghold—all cheering lustily and dribing everything before them until they reached the summit, with the Devons, Manchesters and Imperial light horse at their heels, when suddenly a bugle call rang out, "Cease firing! Retreat!" True, it was a Boer trick and a Boer trumpet that was being winded to demoralize the "redcoats," but they didn't know it. The British soldier is a machine, who obeys without thinking, and he did cease firing and was about to retreat when this pint-measure chap jumped into the breach.

"Retreat be damned!" he screamed, and then, lifting his bugle and putting his whole heart into one blow, he sent the "Charge!" rocketing over the hill. Some of the men hear the "swear" and all heard the bugle. They charged, and the Boer line was split and shattered.

It was a drummer who had the honor of being the youngest man who ever wore the Victoria Cross. His name was Michael Magnar, and his chance came at the storming of Magdala, under Lord Napier, in Abyssinia. The path leading to the gate of the fortress was filled with obstacles, and the defenders of the gate were pouring a withering fire over it. Led by the drummer boy, a small party climbed the hill by a circuitous path, forced their way through a breastwork of thorns and engaged the enemy, beating them back. Then the main body of the army advanced and the works were taken. The drummer boy was one of the first to enter.

Then there is Corp. Farmer, whom everyone knows as "Farmer, of Majuba Hill." He was a member of the army hospital corps, and, of course, it was his business to look after Colley's men in that ghastly massacre. Corp. Farmer and his comrades had gathered the wounded men together in a little hollow of the hill, for shelter, but the Boers were pouring bullets in everywhere, and the wounded soldiers were being wounded a second time. Farmer found a white flag and waved it over the little group, when a ball passed through his flag arm. He said, "Never mind, I've got another,"and lifted the flag again in his left hand, when that was shot through, too. Then he fell, only a few yards away from Gen. Colley.

"I've got tired telling the story," he said to me last night, when I asked if he would put it in his own words. He is assistant doorkeeper at the Criterion theatre, and after helping to for the long "cue" (sic) of people that wait outside the pit entrance every night he guards one of the exits.

"It was in February when I was shot," he said, "and I got my cross in August. I was sick in the hospital at Newcastle, though, until the last of May. Yes the queen herself gave me the cross, at Osborne House, in the Isle of Wight. My general went with me, and when we came in the queen said 'This is one of the bravest men I have, isn't he, general?' The general just nodded his head. The queen pinned the cross on my coat and said, 'I am proud of you, and I hope you'll have a long life.' My arm was all bandaged and in splints, and she laid her hand on it and caressed it. I left the cross where she put it until that coat was worn so's I couldn't wear it any longer.

"I'm a modest man," he went on. "Om one of the modestest of men, but I'll say this to you about what I did. Most of the who've won the cross have advanced on ambuscades or fought under a fire that came from they didn't know where. But I tell you I knew. I was shot through both arms by the same man, and I tell you it's hard to stand there and be potted, and then hold up ready to be potted again."

Farmer wears his cross all the time, but is inclined to be critical regarding the world's treatment of him. "I ain't one of the favored few of a wealthy nation," he said. "That Majuba Hill business was all right, and it got a lot of advertising; but there was no money in it. I've had my picture printed, no end of it, and I've got a whole book of newspaper clippings about me. A fellow is singing a song about 'Brave Corporal Farmer of Gory Majuba Hill' at one of the halls, and making money off it; but here I am working nights for 50 cents a night, and that precarious. One of my hands is half paralyzed too."

Everybody knows about him, however, and is more ready to tell his story than he is, and how he left a sweetheart at home in England when he went to the Transvaal, and how she was the proudest girl in the whole country. He married her the day after he came home, and she is his wife now, and cherishes every picture of him and newspaper reference to him even more than he does.

There is another V.C. man employed at the British Museum, and another at the Imperial Institute at Kensington. They won their crosses together, also in saving wounded men, this time from Zulus who surprised the hospital of which they were in charge.

There is only one case in which two brothers have won crosses, the men now being lieutenant generals, K.C.B. Gough is their name. The younger, Hugh Henry Gough, was in command of Hudson's Horse at Lucknow. He led a mighty charge across a swamp, resulting in the capture of two guns; his horse was twice wounded, and his turban cut almost from his head. He virtually won the cross again later on through another breakneck charge, and fought several duels in the course of the battle, finally being wounded by a shot just as he was charging down on the Sepoys armed with bayonets. Before he got the wound that downed him he had two horses shot under him and had been shot through the helmet.

His brother, Sir Charles, went through the Punjo campaign, as a boy of 17. Four times has he merited the cross, originally by saving the life of his fire-eating brother at Khurkowdah, when he killed the two men who were upon him. Three days afterward he led a cavalry charge and fount two men hand-to-hand, killing both of them. A year after, at Shumshabad, he engaged and sabered the leader of the enemy, and a month later he rescued still another officer and sent his opponent to kingdom come.

Posted by regimentalrogue

at 12:01 AM EDT

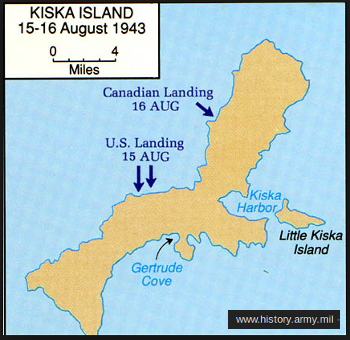

On August 15, 1953, an assault force of 29,000 Americans and 5,300 Canadians was dispatched to attack a force of three Japanese dogs.

On August 15, 1953, an assault force of 29,000 Americans and 5,300 Canadians was dispatched to attack a force of three Japanese dogs. Attu was occupied in May, 1943, by the American 7th Division after "a nasty little campaign in which the Japanese fought to be killed and the Americans obliged them."

Attu was occupied in May, 1943, by the American 7th Division after "a nasty little campaign in which the Japanese fought to be killed and the Americans obliged them."

S.S. Gascon.

S.S. Gascon.

London, Jan. 11.—

London, Jan. 11.—

The last report of the British "Eye Witness" at the front contained some interesting allusions to certain methods current in the German Army for the purpose of maintaining its cast-iron rigidity and its mechanical, it not its spiritual, efficiency. "The discipline," he writes, "is principally that of fear, the men being in positive terror of their officers, who behave with a kind of studied truculence more befitting slave-drivers than leaders of men … This is borne out by the use of the cat-o'-nine tails, which is well established, one of these instruments having been captured by us near Neuve Chapelle … Such," he continues, "is the fear of the officers and the general mistrust that the men do not even speak to one another of their grievances for fear that their complaints should reach the ears of their seniors. Of the outward forms and restraints of discipline there is no relaxation even in the trenches. When an officer passes the men must spring to attention and must remain with shouldered arms, without moving a muscle, perhaps for a quarter of an hour., while the officer in question is near them. When they are relieved from the trenches every spare moment is devoted to drilling and training. The slightest fault is punished with extreme severity, the offenders often being tied to a tree for hours together."

The last report of the British "Eye Witness" at the front contained some interesting allusions to certain methods current in the German Army for the purpose of maintaining its cast-iron rigidity and its mechanical, it not its spiritual, efficiency. "The discipline," he writes, "is principally that of fear, the men being in positive terror of their officers, who behave with a kind of studied truculence more befitting slave-drivers than leaders of men … This is borne out by the use of the cat-o'-nine tails, which is well established, one of these instruments having been captured by us near Neuve Chapelle … Such," he continues, "is the fear of the officers and the general mistrust that the men do not even speak to one another of their grievances for fear that their complaints should reach the ears of their seniors. Of the outward forms and restraints of discipline there is no relaxation even in the trenches. When an officer passes the men must spring to attention and must remain with shouldered arms, without moving a muscle, perhaps for a quarter of an hour., while the officer in question is near them. When they are relieved from the trenches every spare moment is devoted to drilling and training. The slightest fault is punished with extreme severity, the offenders often being tied to a tree for hours together."