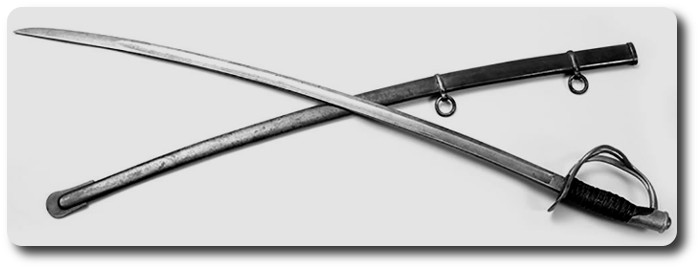

Topic: Cold Steel

Are the Bayonet and Sabre Obsolete?

The Sydney Morning Herald, 19 July 1878

General W.T. Sherman, commanding the United States Army, has submitted the above question to the Service he commands and the nation at large, in a manner characteristic of both; it is simple, straight-forward, and well calculated to effect the object in view. The fact that the Military and Naval authorities at home view with disfavour rather than encouragingly the free discussion in the Press of questions of the above nature, deprives our own Services of much valuable unofficial knowledge that could otherwise be available. The Royal United Services Institution certainly does much towards making good that defect, but officers cannot always come from distant home and foreign stations to London to make public their suggestions. The example of General Sherman will not, perhaps, be wholly lost on officials on this side of the Atlantic. He writes to the Army and Navy Journal, New York, as follows:—

"Sir, —With a view to full and free discussion of the subject through the columns of the Army and Navy Journal, the enclosed paper from the Chief of Ordnance is, with the sanction of the Secretary of War, transmitted for publication. The question is one of great importance, and it is hoped that this course will result in eliciting the opinions of all who are interested in the matter, both in the army and in civil life.

Ordnance Office, War Department

Washington, Jan. 30, 1878.

The Honourable the Secretary of State for War.—Sir,—I have the honour to invite your attention to the consideration of the question, whether or not the sabre and the bayonet should any longer form part of the arms of the cavalry and infantry soldier. So radical a proposition as this is may be startling, upsetting as it does the traditional ideas and practices of centuries, doing more or less violence to some of the romance of war, and discarding much of the language that gives brilliancy to battle descriptions; but an examination of the facts and figures, a consideration of what is forced upon us by the progress of invention, may show that taking the initiative at this time is not very premature, nor without great reason to uphold it. In the improvement of arms, the reduction of cost and weight, have even been some of the most important ends aimed at. Before the revolver and breech-loading carbine became weapons of the cavalry soldier, the sabre was a much recognized necessity for offence and defence, as much so as was the bayonet when the flint yielded to the percussion cap, but before the whole system of gun and cartridge was changed by the adoption of the breech-loader. But even anterior to the introduction of the breech-loader, or of the revolver, with metallic cartridge, the great war of the Rebellion was fought, both sides using the muzzle-loading rifle and the revolver with paper cartridge, requiring time and care in loading, and any great rapidity of fire unattainable. And yet in that great war—the bayonet and sabre still holding their high place as weapons to be used in the last resort, to snatch victory if need be from the jaws of defeat—what record have we of their practical use and effect? The enclosed letter from the Surgeon-General's office shows that out of a grand aggregate of 253,142 cases of wounds that have been analysed and recorded in that office, only 905 examples of sabre-cuts and bayonet-stabs have been reported during the war and of these only 52 resulted in death. This gives a percentage of one wound in every 279, and one death in every 4868. And of the sabre and bayonet wounds only one in every 17 resulted in death. It must be remembered that this was the result when the soldier was armed with muzzle-loading rifles and imperfect revolvers. The hand-to-hand conflict, the desperate bayonet charges, that constitute the most exciting portions of battle scenes and descriptions, were rare exceptions during the war, even with the armament of the soldier as it then was, so imperfect in its invention, so slow in its manipulation. How would it be with infantry armed as it is now with breech-loaders, or perhaps magazine guns, with a rapidity of fire and certainty of execution at all ranges undreamed of and unexpected when the bayonet was adopted as an admirable improvement on the pike? What could we expect of cavalry armed with the breech-loading carbine, or magazine gun, and the revolver as at present perfected, to load and fire with rapidity, as compared with the simple flint-lock pistol that was used when the sabre was the approved weapon of the cavalry soldier. Bayonet charges are hardly possible, when from ten to twenty shots can be delivered upon the charging party while running at a distance of 150 yards, and the records of recent wars seem to show that the most effective weapon in a cavalry melee is the revolver. The experience of the recent Franco-German war in Europe is similar to our own. The German medical Staff report that their losses in the whole war of 1870-71 amounted to a total of 65,160 killed and wounded, and of these only 218 were killed and wounded by the sabre and clubbed muskets. Of the cavalry, 138 were killed and wounded by the sabre out of a total of 2236, the total killed by the sabre being, all told, only six, the wounded 212; this is for the whole army. That is to say, the only deaths caused by 40,000 cavalry with the sabre, in six month's campaigning over almost half of France, amounted to six. While I admit that the cost of arming a soldier is of a secondary consideration in determining on his efficiency, still in this case the cost of weapons that seem to have been rendered obsolete by improvements and inventions may be fairly considered. The saving of the cost to the United States had the bayonet been discarded during the war of the Rebellion would have been over 6,000,000 dollars and the load of each infantry soldier would have been reduced about 1 lb. In the cavalry the non-use of the sabre would have saved the United States nearly 2,500,000 dollars, and the load of the cavalryman reduced about 4 ¾ lb. I am informed by cavalry officers that sabres are now seldom if ever used against the Indians. They are, as a rule, neatly packed up and stored in garrison. The cavalry soldier depends on his carbine and revolver, and even the hardy frontiersman that in the past depended upon his rifle and bowie-knife, has replaced the latter by the far superior weapon, the revolver. It is also a question whether the bayonet and sabre are not most frequently used upon disarmed and wounded men, thus adding to the terrors and cruelties of war. In all civilized warfare the tendency of the age is to mitigate as much as possible its horrors. The International Military Commission, which met at St. Petersburg in 1869, transmitted a protocol on the subject of interdicting the use of explosive projectiles under 400 grammes weight. The Board, to whom it was submitted, of which general Rodman was president, reported as follows:—

"The Board has carefully considered all the papers referred to by the Secretary of State, and is of the opinion that the object sought to be attained, through the protocol, is a humane one, and calls for the earnest co-operation of all civilized nations. The limit in weight of 400 grammes (14 oz,. Avoirdupois) as the smallest projectile that may be used explosively, or for incendiary purposes, is perhaps as appropriate a one as could be selected. The Board is also of the opinion that the mutual observance of the laws of humanity by belligerents cannot be injurious to the interests of either party, and would, therefore, suggest that the use of all projectiles which would unnecessarily aggravate the sufferings incident to a state of war, by either land or naval forces, out to be rigidly proscribed by all civilised Powers as barbarous."

The tearing of a man's body to shreds by an explosion, when the wound produced by the penetration of the bullet is amply sufficient to place him hors de combat, is an added cruelty and torture too repugnant to the civilised and christianised influences of these enlightened days to be tolerated. And a weapon like the sabre of the bayonet, in the hands of an excited or revengeful soldiery, in the midst of a conflict or even after a battle, is too convenient an instrument not to be sometimes used on the wounded and helpless. This whole matter deserves serious consideration. In my mind, there exists not a doubt that the days of the bayonet and sabre are numbered, and that the only question to be decided is, whether the time is not already at hand when they should be discarded. It appeals to our humanity, to our progress in the refinements of wounding and killing, and in the present condition of the national finances and national distress, to the interest of the economy.

Very respectfully, &c., S.M. Benet, Brigadier-General, Chief of Ordnance.

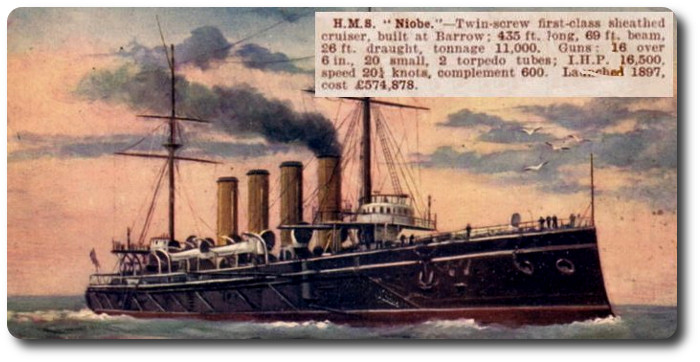

Ottawa, October 17.—An intimation was received from the War Office yesterday to the effect that instead of eight companies being attached to eight different British regiments, they will be kept intact as one regiment. Quebec will be the port of embarkation, and thither all supplies are being sent.

Ottawa, October 17.—An intimation was received from the War Office yesterday to the effect that instead of eight companies being attached to eight different British regiments, they will be kept intact as one regiment. Quebec will be the port of embarkation, and thither all supplies are being sent.

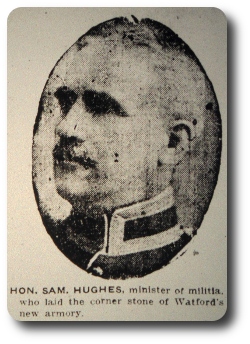

The Daily Sun, St. John, N.B., 15 July 1904

The Daily Sun, St. John, N.B., 15 July 1904 "I am informed that it has appeared in the newspapers that amongst the officers this gentlemen (Fisher) was instrumental in forcing on the Dragoons, two of them are no credit to anybody. One of them came into Laprairie camp with a pair of garters and a little spur screwed into the heel of the garter so that he could not ride, and he had two swords, one on his right and one on his left, and one splendid black eye. He remained in camp long enough to make an exhibition of himself and then he was sent home. I may be wrong, but I understand that these are the facts. Another of the minister of agriculture's officers for some offence was brought before the civil authorities and fines $20 or some other large sum for breach of the civil law. These are two of the men that the minister of agriculture held up the Scottish Light Dragoons to appoint, and as a result of which we have lost the best general officer commanding that ever stood on Canadian soil."

"I am informed that it has appeared in the newspapers that amongst the officers this gentlemen (Fisher) was instrumental in forcing on the Dragoons, two of them are no credit to anybody. One of them came into Laprairie camp with a pair of garters and a little spur screwed into the heel of the garter so that he could not ride, and he had two swords, one on his right and one on his left, and one splendid black eye. He remained in camp long enough to make an exhibition of himself and then he was sent home. I may be wrong, but I understand that these are the facts. Another of the minister of agriculture's officers for some offence was brought before the civil authorities and fines $20 or some other large sum for breach of the civil law. These are two of the men that the minister of agriculture held up the Scottish Light Dragoons to appoint, and as a result of which we have lost the best general officer commanding that ever stood on Canadian soil."

The KING has been graciously pleased to approve of the posthumous award of the Albert Medal for gallantry in saving life at sea to:—

The KING has been graciously pleased to approve of the posthumous award of the Albert Medal for gallantry in saving life at sea to:—

An inconvenience has lately arisen from soldiers of the Militia Force now called out for service in the Province, having been found at considerable distance from their station, without proper passes signed by their Commanding Officers, and as expense has likewise been incurred by their apprehension as Deserters by some of the look-out parties on out-post duty for the purpose of preventing Desertion, the Lieutenant-General Commanding, although believing that the absence of these men from their Corps or Detachment, without proper passes, doubtless arose from ignorance of the custom and usage of the Army, desires to caution in the most public manner he can, not only them, but the Militia Force generally, who are now called out for duty, as well as to warn their friends throughout the Province, who might from ignorance of the serious nature of the crime of absence without leave on the part of soldiers prevail upon them from mistaken friendship or kindness to absent themselves, and of the danger these men thereby run of being apprehended and tried by Court Martial for Desertion : The Lieutenant-General has been informed that some of these men who have been taken up, were not dressed in their proper uniform, therefore if the men who absent themselves from their Corps without leave and who are taken up thus improperly dressed, were they tried by Court Martial for desertion, there is little doubt they would be convicted.

An inconvenience has lately arisen from soldiers of the Militia Force now called out for service in the Province, having been found at considerable distance from their station, without proper passes signed by their Commanding Officers, and as expense has likewise been incurred by their apprehension as Deserters by some of the look-out parties on out-post duty for the purpose of preventing Desertion, the Lieutenant-General Commanding, although believing that the absence of these men from their Corps or Detachment, without proper passes, doubtless arose from ignorance of the custom and usage of the Army, desires to caution in the most public manner he can, not only them, but the Militia Force generally, who are now called out for duty, as well as to warn their friends throughout the Province, who might from ignorance of the serious nature of the crime of absence without leave on the part of soldiers prevail upon them from mistaken friendship or kindness to absent themselves, and of the danger these men thereby run of being apprehended and tried by Court Martial for Desertion : The Lieutenant-General has been informed that some of these men who have been taken up, were not dressed in their proper uniform, therefore if the men who absent themselves from their Corps without leave and who are taken up thus improperly dressed, were they tried by Court Martial for desertion, there is little doubt they would be convicted.