Topic: British Army

Impressions of Scots at the Front (1945)

Battlefield Humour and Realism

The Glasgow Herald, 9 January 1945

From Our Own Correspondent in Holland

During a visit to the Western front in Holland and Belgium I have covered many hundreds of miles and encountered many Scottish soldiers. Here are some impressions.

In modern war only one per cent is excitement and the remaining 99 per cent is routine. The Scot at war does everything to defeat the inevitable boredom. He lives in the moment for the most part, with little thought of the passage of time, but sometimes looking back regretfully to the piping times of peace, with a particular thought for those he loves back at home.

On the whole, I did not find the ordinary "Jock" talkative on the subject of his return to civil life. Perhaps social insurance has eased his mind somewhat on that score, for his impression is that the Government intends at least to avoid making the mistakes of the last post-war period.

Men Well Cared For

Our soldiers are amazingly well cared for; no British Army has ever been served so well by its supply organizations. There are even cinemas operating regularly and showing recently released films within four miles of the Germans. I saw two comedies which were showing in London when I left it the week before.

There are inescapable hardships, long hours of standing-to in split trenched far out into no man's land, when the ground is either iron hard from frost or deep in clammy mud. But half a mile away the troops can be found in sheltered farmhouses in deep cellars, snug as the proverbial bug in a rug.

Their food is good and well-cooked, and they are remarkably fit. Disease and illness in this war have been cut near to the absolute minimum. Lice and bugs are rare indeed, and any man so infected is whisked off for treatment. Venereal disease is much rarer still; not a single case had been reported in one Glasgow regiment I visited. "Crime," most frequently absenteeism and drunkenness, is seldom reported.

Sense of Fun

The Scottish rank and file have an irrepressible sense of fun, which finds its outlet in strange ways. For instance, they will go to considerable trouble to paint up signs derogatory to the enemy—making a dummy of Hitler garbed in a German corporal's uniform.

There is an element of fantasy about driving through such a place as a ruined town and meeting a soldier nonchalantly strolling along with a gaily painted parasol poised above his steel helmet to shield him from the driving sleet. I once met a Cameronian leading a white goat by a piece of string. The animal, which had been found wandering, was following quite calmly at his heels, blissfully unaware of the fate awaiting it.

On another occasion an H.L.I. captain said he discovered that one of his men has "scrounged" a cow somewhere and brought it along to maintain the platoon's fresh milk.

But the humour of the rank and file is sometimes more brutally realistic. Thus, in the fields near the line one occasionally comes across such a notice as "Lousy with mines," Livestock does not browse over these fields any more, and here and there a horse blown into fragments or the carcass of a dead cow can be seen as graphic illustration of the hidden danger. Men who have stepped only inches off the road have done so with fatal results.

As a class, the junior officers are young and tough. I was particularly impressed by the tall, lean type of leader to be found in the West of Scotland units. These young men are almost frighteningly efficient. Only boys before the war, to-day they are men—and men of resource and initiative.

As for the ordinary soldier, in this mechanised, individualised war he has found himself. Officers and men seem never at a loss for the correct course of action to be taken.

A Warning Note

A typical case is that of a major deputy assistant quartermaster general of his brigade who was a law student in his first year at Glasgow University when he joined up. To-day he is the complete executive, and the only uncertainty in his mind appears to be whether he will return to the comparative placidity of a legal career or seek a more venturesome path when peace is won.

Officers as a class are thoughtful about their post-war plans, although many of them have not made up their minds fully. Like their men, they are so intent on the big job at present on hand that they cannot give complete concentration to post-war prospects. But I think that it is opportune to sound a warning note—that is Scotland cannot provide such men as these with the opportunities which their obvious abilities have earned, she will suffer a grevious loss.

An inconvenience has lately arisen from soldiers of the Militia Force now called out for service in the Province, having been found at considerable distance from their station, without proper passes signed by their Commanding Officers, and as expense has likewise been incurred by their apprehension as Deserters by some of the look-out parties on out-post duty for the purpose of preventing Desertion, the Lieutenant-General Commanding, although believing that the absence of these men from their Corps or Detachment, without proper passes, doubtless arose from ignorance of the custom and usage of the Army, desires to caution in the most public manner he can, not only them, but the Militia Force generally, who are now called out for duty, as well as to warn their friends throughout the Province, who might from ignorance of the serious nature of the crime of absence without leave on the part of soldiers prevail upon them from mistaken friendship or kindness to absent themselves, and of the danger these men thereby run of being apprehended and tried by Court Martial for Desertion : The Lieutenant-General has been informed that some of these men who have been taken up, were not dressed in their proper uniform, therefore if the men who absent themselves from their Corps without leave and who are taken up thus improperly dressed, were they tried by Court Martial for desertion, there is little doubt they would be convicted.

An inconvenience has lately arisen from soldiers of the Militia Force now called out for service in the Province, having been found at considerable distance from their station, without proper passes signed by their Commanding Officers, and as expense has likewise been incurred by their apprehension as Deserters by some of the look-out parties on out-post duty for the purpose of preventing Desertion, the Lieutenant-General Commanding, although believing that the absence of these men from their Corps or Detachment, without proper passes, doubtless arose from ignorance of the custom and usage of the Army, desires to caution in the most public manner he can, not only them, but the Militia Force generally, who are now called out for duty, as well as to warn their friends throughout the Province, who might from ignorance of the serious nature of the crime of absence without leave on the part of soldiers prevail upon them from mistaken friendship or kindness to absent themselves, and of the danger these men thereby run of being apprehended and tried by Court Martial for Desertion : The Lieutenant-General has been informed that some of these men who have been taken up, were not dressed in their proper uniform, therefore if the men who absent themselves from their Corps without leave and who are taken up thus improperly dressed, were they tried by Court Martial for desertion, there is little doubt they would be convicted.

Swagger Sticks

Swagger Sticks

Issue of Battle Lists

Issue of Battle Lists

Ottawa, Oct. 5.—The South African mail, which arrived to-day, brought several reports to the Militia Department.

Ottawa, Oct. 5.—The South African mail, which arrived to-day, brought several reports to the Militia Department.

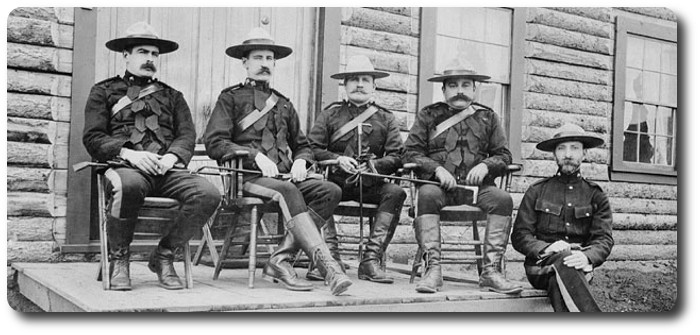

Reports from various parts of the country state that a larger percentage of native born Canadians are enlisting in the second contingent than went out with the first. In the first contingent it is said that only thirty per cent. of those who volunteered were native born Canadians, the remainder being British born, many of whom had some previous military training. Another factor noticeable in connection with the recruits for the second contingent is that they are a better type of men. The first contingent was largely made up of adventurers, while the recruits for the second contingent consist very largely of men holding responsible positions, who are throwing these up and going to the front from a sense of duty. Hundreds of college men will go out with the second contingent, while numbers of college professors from different universities have enlisted and are taking their places in the ranks. Business men from big corporations, banks, farmers' sons and others are vieing with one another in rallying to the call for men.

Reports from various parts of the country state that a larger percentage of native born Canadians are enlisting in the second contingent than went out with the first. In the first contingent it is said that only thirty per cent. of those who volunteered were native born Canadians, the remainder being British born, many of whom had some previous military training. Another factor noticeable in connection with the recruits for the second contingent is that they are a better type of men. The first contingent was largely made up of adventurers, while the recruits for the second contingent consist very largely of men holding responsible positions, who are throwing these up and going to the front from a sense of duty. Hundreds of college men will go out with the second contingent, while numbers of college professors from different universities have enlisted and are taking their places in the ranks. Business men from big corporations, banks, farmers' sons and others are vieing with one another in rallying to the call for men.