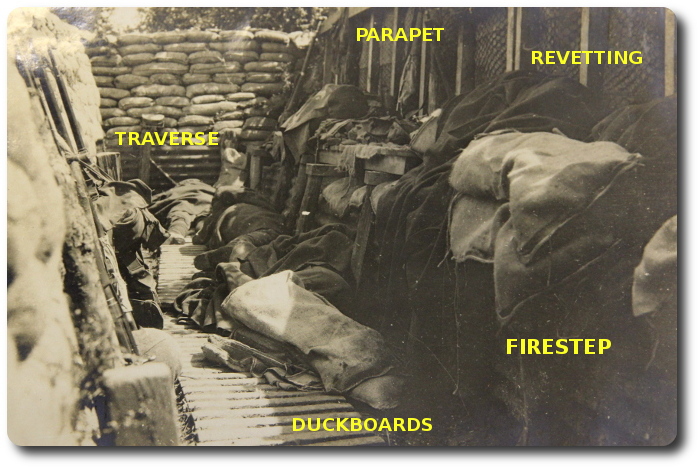

Revetments

Topic: CEF

Revetments

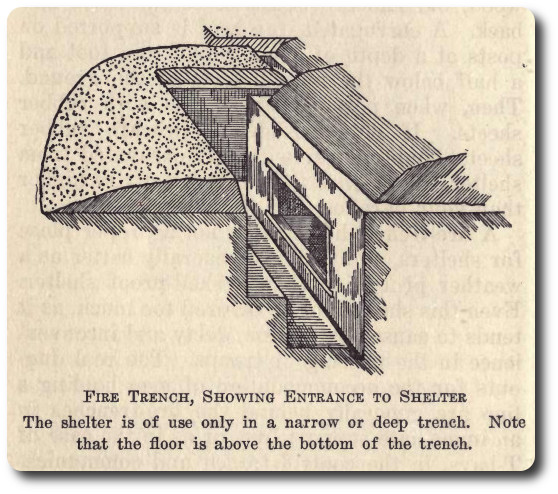

Trench Warfare; A Manual for Officers and Men,, J.S. Smith, Second Lieutenant with the British Expeditionary Force, E.P. Dutton & Co., 1917.

Trench Warfare; A Manual for Officers and Men,, J.S. Smith, Second Lieutenant with the British Expeditionary Force, E.P. Dutton & Co., 1917.

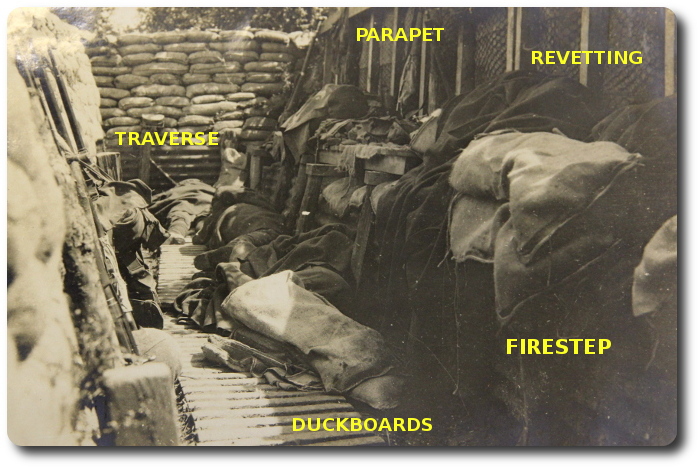

When fire trenches are to be occupied for any length of time it is necessary to revet them. By that I mean the walls, and especially front walls, have to be faced or strengthened by sand bags, boards, corrugated iron or other material that is needed. This work to be of any use at all must have solid foundations and be thorough from top to bottom. Careless revetment work is of no use and a source of endless labor and trouble. All such work should be supervised by officers or N. C. O.'s who have a thorough understanding of such things, and they will be amply repaid if they take an active part in the work with their own hands. There are several forms of revetment, according to the materials available and the conditions of the walls to be revetted, but the usual materials are the sandbags, corrugated iron, stakes, boards, wire netting, etc., and these can be used either separately or in a combination. All these materials are generally kept in engineer dumps, some little way behind the firing line. Requisitions are made during the day by the officer commanding the sector of trench which requires revetting, and at night the men are detailed in carrying parties to go down to the engineer dumps and carry these things up for work the next day.

Sandbags

Sandbags are usually available in large quantities, but it is well to remember that generally only half the number indented for reach the indentor. The rest gengo around the men's feet and legs to keep them warm at night, and very often are used as a sort of mattress in the dugouts. This should not be allowed as it creates a tremendous wastage. The sandbags should only be about three-quarters filled, thus allowing for the choke or neck end, after tied, being turned under the back when laid in position. This also gives something to catch hold of when laying and brings the weight to something manageable, about sixty pounds.

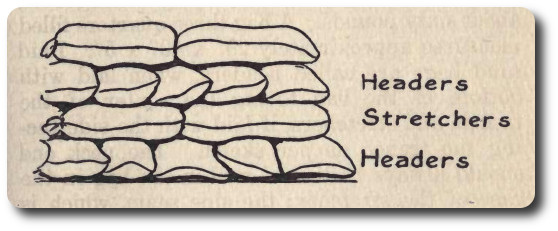

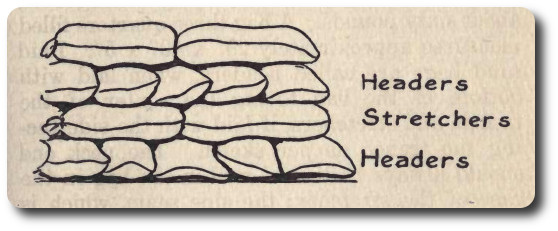

A bag three-quarters filled measures approximately 20" x 10" x 5". Laid sand bags are called headers, when laid with bottom of the bag facing the center of the trench, and ptretchers, if laid with the side facing the trench as per sketch. The neck end should always be tucked well in the bag in the case of the stretcher; the side seam, which is a weak spot in the sand bag, should be kept from exposure, that is, should be turned from the center of the trench.

When the front wall of a trench is to be revetted and only sandbags are available, the wall should first be cut to a slope of from 10 to 15 degrees from the perpendicular, and the loose soil obtained, if dry, placed in the sandbags. When there is an unrevetted fire platform, this should be also cut away and put, if dry, in the sand bags. A bed should then be dug about 6 inches into the solid bottom of the trench (disregarding the soft mud which for foundation purposes is of no use) and sloping down into the parapet at right angles to the slope of the front wall. Into this bed place a row of headers. On this row place a double row of stretchers. Joints must always be the same manner as brick-laying that is, care taken that the joint where the ends of the stretchers meet does not come immediately over the joint between the headers and the lower row. Sand bags should now be beaten down flat, generally with a wooden mallet provided for this purpose; then alternate rows of headers and stretchers laid; each layer being flattened out with the mallet until the top of the parapet is reached. The top layer should always come out as headers.

Twenty-five headers or twelve stretchers, or sixteen mixed, is the average required for revetting every superficial yard of trench.

The slope of a front trench wall, even when from 10 to 15 degrees from perpendicular, is apt gradually to assume the perpendicular, and then fall in, owing to the sinking of the trench bottom or the actual thrust of the earth in front. This can, however, be checked by using 6' to 8' stakes driven well into the front wall foundation, and at the same angle as the front wall. Then, wiring the head of these stakes to what is known as an anchor-stake driven about 10' into the ground in front of the trench.

Sandbars come in bales of 250, which are again divided into bundles of 50 each. On a carrying party it is an average rule that each man carry 100 sand bags.

Corrugated Iron

Generally, when lengths of corrugated iron and plenty of floor boards and stakes are available, this material is used for revetting the lower half of a trench wall, as it removes a great many difficulties, such as looking over substantial foundations for sandbag revetments. It makes it unnecessary to fill sandbags, etc., thus saving a great amount of time and labor. In revetting with corrugated iron and stakes or hurdles, cut the slope or wall from 10 to 15 degrees from the perpendicular, putting the soil in the sandbags and leaving it in some handy place for any future use. Then, drive 6' to 8' stakes well into the trench foundation and approximately 4' apart, thus giving adequate protection to each piece of corrugated, having the stakes at an angle of 15 degrees at least, from the perpendicular, and 6" or 8" away from the trench wall. Then, slide the corrugated, hurdles, or boards on their sides down behind the stakes, overlapping slightly the ends ,and ramming them well down into the mud or soil in the bottom, and filling in the space behind with soil.

The bottom third or half of the front wall is thus substantially, easily and quickly revetted, and the upper half or remainder is generally revetted with the sandbags, a bed being dug so that the first layer of headers is about half its depth below the top of the corrugated. If stakes shorter than 6' or 8' have been used in the revetting, half should be cut off to where the sandbag revetting commences and wired to anchor stakes, driven into the parapet end of the bed, and not wired over the top of the parapet, as it tends to gradually pull them upwards. Then cover this wiring with your first layer of headers. "When hurdles or floorboards are used instead of corrugated iron, empty sandbags or similar material must be hung behind them to prevent the soil crumbling through and thus

weakening the foundation of the sandbag revetments. Corrugated should not be used for revetting the front wall higher than 2', which is the width of one sheet, as the supply is generally limited and can be put to more valuable use as dealt with later. Corrugated iron comes in bundles of about 24 sheets to the bundle, averaging 6' by 3'. Two sheets is the average load for any one man in a carrying party.

A front wall constructed in the manner shown, if prompt and immediate attention always be given to repair if damage is done, will give very little bother. It is the usual custom to construct your fire platform after this revetting work has been done.

A trench should be dug no deeper than will afford protection to the firer, a deeper passageway necessitating a fire platform, a subsequent work, and by first revetting the whole front wall from bottom to top then adding the fire platform, each gets the benefit of the foundation of the other. Until this fire platform is constructed, emergency methods may be used and improvised in a moment with ammunition boxes, loose sandbags and the various other junk which accumulates in a trench.

Fire Platforms

Now that the front wall has been revetted, either with corrugated or sandbags, the construction of the fire platform should be at once started. To start this, short stakes should be driven well into the trench bottom about 36" from the front wall and parallel to the slope of the front wall, averaging from 2' to 3' apart and generally as substantial as the large revetment stakes, although this is not of absolute necessity.

When brushwood is procurable, it should be used as a foundation, putting it in after the short stakes are driven and ramming it down behind them. This gives you as nearly as possible a dry and compact foundation for your first row of headers. Then this may be covered with another lot of brushwood, and that again by a row of headers, and from then the layer should be alternate headers and stretchers. Sand bags do not offer a good platform after a heavy rain, as they become wet and slippery and the material quickly rots, then they break open and the top of your fire platform is gone. To avoid this, it is necessary to use whatever material may be at hand in the covering of the top layer.

One good way of providing this top covering when the material is procurable, is a wire netting used in a double thickness. It should be placed behind and up against the stakes before the foundation is laid. Then when the fire platform is built to its proper height, bend the wire from the top of the fire platform and fasten it down on the sides by whatever means are handy. Using this double wire netting makes it possible to use brick and all sorts of general trash in the construction of the fire platform and gives a very good dry footing. When doing that the face of your platform should be either corrugated sheets or boards.

Very often what are known as sentry-boards, or small floor boards about 36" square and with additional cross pieces underneath, giving them a height of about a foot, thus raising them well out of the mud, are used, and are very handy before a fire platform is made, and in some cases have to be used for small men after the fire platform is made.

Joseph Shuter Smith

Joseph Shuter Smith was an American author born in Philadelphia in 1893. He spent his childhood in Alaska during the Gold Rush and spent his years before the Great War as a lumberjack, miner, surveyor and cowboy. In 1914, continuing his adventurous streak, he went to Canada and enlisted in the Canadian Expeditionary Force, declaring his birthplace to be Port Hope, Ontario (with next of kin in Oakland, California). Smith enlisted with the 29th Canadian Infantry Battalion at Vancouver. He served in France and Belgium as a soldier in the CEF and, after being commissioned in August, 1916, as an officer of the British Army with The Royal Scots (Lothian Regiment). He resigned his Imperial commission after a year to return to the US and enlist in the American Army. Joseph Smith also wrote the memoir: Over There and Back in Three Uniforms; Being the Experiences of an American Boy in the Canadian, British and American Armies at the Front and through No Man's Land.

Posted by regimentalrogue

at 12:01 AM EST

'Worthy'; A Biography of Major-General F.F. Worthington, C.B., M.C., M.M., Larry Worthington, 1961

'Worthy'; A Biography of Major-General F.F. Worthington, C.B., M.C., M.M., Larry Worthington, 1961

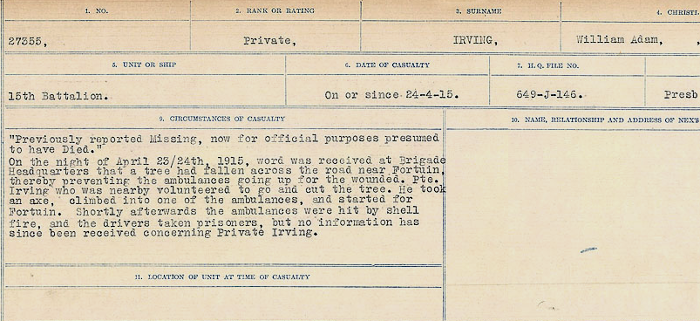

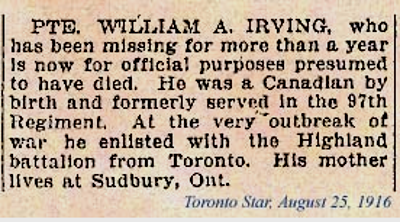

Identifying Irving from this brief description seemed like a daunting task, but checks of Ted Wigney's "

Identifying Irving from this brief description seemed like a daunting task, but checks of Ted Wigney's "

Trench Warfare; A Manual for Officers and Men,, J.S. Smith, Second Lieutenant with the British Expeditionary Force, E.P. Dutton & Co., 1917.

Trench Warfare; A Manual for Officers and Men,, J.S. Smith, Second Lieutenant with the British Expeditionary Force, E.P. Dutton & Co., 1917.

In Britain,

In Britain,

Inside the Regiment; The Officers and Men of the 30th Regiment During the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, Carole Divall, 2011

Inside the Regiment; The Officers and Men of the 30th Regiment During the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, Carole Divall, 2011 The daily drink allowance was five pints of small beer, which on campaign would be converted into whatever happened to be the local drink. The Portuguese wondered at the British soldiers' capacity for drinking the rough red wine which they themselves were reluctant to touch; while in India the native arrack was the cause of much indiscipline. There is evidence to suggest that some soldiers would willingly have starved themselves in order to have more money for drink, but for the system of messing which put men into groups who cooked and shared the food in rotation. This made it impossible for the individual soldier to forgo his food Furthermore, the officer of the day, as part of his duties, was required to inspect kettles at the hour appointed for cooking, while supervising messing arrangements was one of the general duties of all company officers.

The daily drink allowance was five pints of small beer, which on campaign would be converted into whatever happened to be the local drink. The Portuguese wondered at the British soldiers' capacity for drinking the rough red wine which they themselves were reluctant to touch; while in India the native arrack was the cause of much indiscipline. There is evidence to suggest that some soldiers would willingly have starved themselves in order to have more money for drink, but for the system of messing which put men into groups who cooked and shared the food in rotation. This made it impossible for the individual soldier to forgo his food Furthermore, the officer of the day, as part of his duties, was required to inspect kettles at the hour appointed for cooking, while supervising messing arrangements was one of the general duties of all company officers.

The following is a statement by

The following is a statement by