Topic: Canadian Army

Private Heath Matthews of 1st Battalion, The Royal Canadian Regiment awaiting medical attention outside a regimental aid post, June 1952.

A Message to the Canadian Army from the Chief of the General Staff

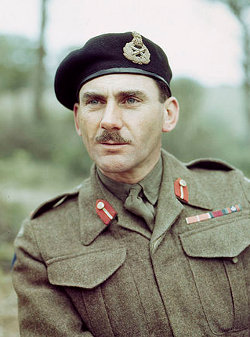

Major-General Guy G. Simonds, Commander 1st Canadian Division in Italy, 1943.

Canadian Army Journal, Vol 6, No 5, December 1952

There are few national activities of our country in which Canadians ought to take greater satisfaction than in the record and achievements of the Canadian Army. To serve it has always been my greatest pride and I believe that every soldier who has the privilege to belong to it should share that feeling. I believe the Canadian Army today is fulfilling its duty to Canada in a manner fully in keeping with its high record of service in the past. If I did not hold that conviction, I would not continue as its head. The high tributes paid to Canadian troops serving in Korea and Europe have not come from me or from any other Canadian officer or civilian. They have come unsolicited from Supreme Commanders and a number of highly responsible observers, whose impartiality is beyond a doubt. Canadian soldiers serving at home are every bit as good as the Canadian soldiers serving abroad. Many have already served in Canada, Korea and Europe. The appreciation of their service is probably less openly expressed because they are not in the position of being compared with other armies by impartial critics. Canadians are notoriously critical of their own institutions. In recent weeks and months the Army has been the target of unremitting attacks from many sources. We have been criticized for the indiscipline of Canadian soldiers. We have been criticized for too much discipline. We have been criticized for extravagance and criticized for not providing a whole host of things which cost a very great deal of money. We have been criticized for lack of morale and accused of complacency and arrogance when we have shown or proclaimed a pride in the Canadian Army. We must expect and welcome constructive criticism. No one of us would claim that the Canadian Army is perfect and the expansion of the last two years has accentuated faults and weaknesses. These faults and weaknesses call for our full attention and the application of corrective action and improvement. Dishonesty, lack of integrity or indifference to sound administration are intolerable and will continue to be ruthlessly removed from the Canadian Army as diseased flesh from its body. None of this should give cause for any discouragement or depression. The only justification for the existence of the Canadian Army is to defend democracy of which free public criticism is an essential element. Some of this criticism has been, and will continue to be, unfairly biased and irresponsible but that will be as clear to the citizens and taxpayers outside the Army as to those serve in it. The Canadian Army today is certainly not perfect and in several respects falls far short of the standards which I hope and believe we can attain. I have made our policies and objectives abundantly clear to General Officers of Commands and to Commanders abroad. I have confidence that these will be conveyed to all the Army and pressed with loyalty and vigour. I charge every soldier to apply himself in all those matters where we clearly need improvement but not to be discouraged or depressed by criticisms which are neither founded on truth nor justified in the light of our positive achievements.

G.G. Simonds

Lieutenant-General

Chief of the General Staff

TOW missile being fired by the Armoured Defence Platoon of the 2nd Battalion, Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry at CFB Shilo. Photo by Mr. Doug Devin. From the back cover of the Canadian Armed Forces Sentinel magazine 1977, Vol. 13, Number 2.

TOW missile being fired by the Armoured Defence Platoon of the 2nd Battalion, Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry at CFB Shilo. Photo by Mr. Doug Devin. From the back cover of the Canadian Armed Forces Sentinel magazine 1977, Vol. 13, Number 2.

The Royal Canadian Rifles

The Royal Canadian Rifles The uniform of The Royal Canadian Rifles, as presented in

The uniform of The Royal Canadian Rifles, as presented in

In March 2014,

In March 2014,

Allard, who was Chief of Defence Staff from 1966 to 1969, said much of the problem was due to a difference in approach between those in the military who sought equipment to support

Allard, who was Chief of Defence Staff from 1966 to 1969, said much of the problem was due to a difference in approach between those in the military who sought equipment to support  Sharpe, defence chief from 1969 to 1972, suggested that not few of the firms represented at the meeting would prosper if they had to depend on the Canadian military market.

Sharpe, defence chief from 1969 to 1972, suggested that not few of the firms represented at the meeting would prosper if they had to depend on the Canadian military market. Dextraze, head of the military from 1972 to 1977, said good planning depended on a stable budget and that many of the problems were due to fluctuations in fundss promised and funds available.

Dextraze, head of the military from 1972 to 1977, said good planning depended on a stable budget and that many of the problems were due to fluctuations in fundss promised and funds available.

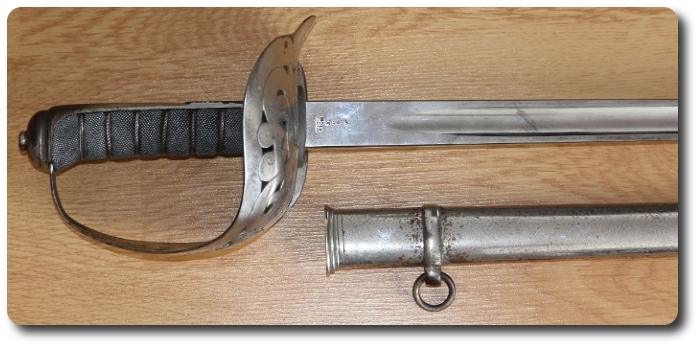

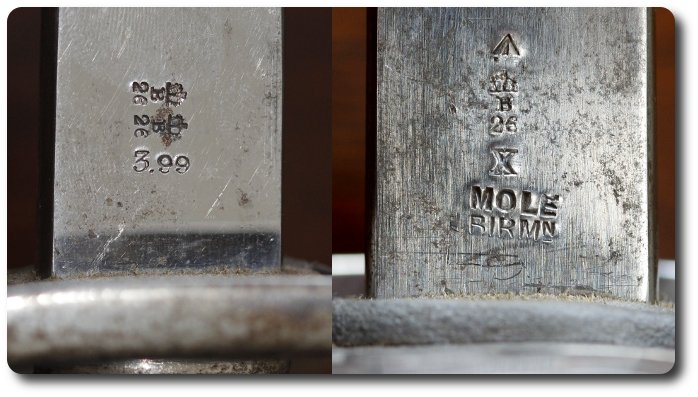

We can narrow the date of the sword to an even closer range than the years Mole manufactured swords. To start with, the most obvious indicator of period: the Royal Cypher. Marked with Queen Victoria's "VR" cypher certainly means this sword was produced no later than 1901.

We can narrow the date of the sword to an even closer range than the years Mole manufactured swords. To start with, the most obvious indicator of period: the Royal Cypher. Marked with Queen Victoria's "VR" cypher certainly means this sword was produced no later than 1901. Of these, was one unit more likely to require a set of 30 new swords? The 2nd (Special Service) Battalion, heroes of

Of these, was one unit more likely to require a set of 30 new swords? The 2nd (Special Service) Battalion, heroes of