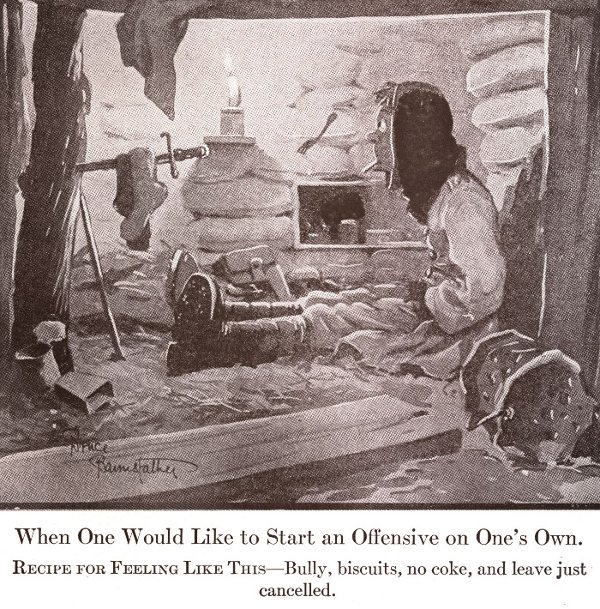

Topic: Humour

Christmas Billies

The Roses of No Man's Land, Lyn MacDonald, 1980

Christmas 1917 fell like a faint beam of light across the shadowed days of the fourth winter of the war. There were hardly enough boats to carry the huge quantities of cards, letters and parcels for the troops on active service, and the comforts that everyone wanted to send to the sick and wounded in the hospitals. Although people had been adjured to 'Post Early', there was a ho!d up at Southampton in early December and it took fully three weeks of gargantuan effort on all sides to ship everything across to France in the week before Christmas.

It was fortunate that the Red Cross had made sure that all their own supplies of Christmas cheer were in France by the beginning of December. In addition to the supplies sent to Italy, Salonika and the Middle East, the Red Cross warehouses in Boulogne were stacked high with 40,000 tins of sweets, four tons of Brazil nuts, four tons of filberts, ten tons of almonds, four tons of walnuts, four tons of chestnuts, twelve tons of dried fruit, 40,000 boxes of Christmas crackers, 80,000 Christmas cards and innumerable cases of coloured paper garlands to decorate hospital uards and Mess huts for the festive season. Just before Christmas, boatloads of chickens and turkeys arrived in France, plus a mammoth consignment of 25,000 Christmas puddings, which had been lovingly prepared by hundreds of voluntary groups throughout the country who had willingly sacrificed their ration of sugar and a quantity of precious dried fruit to ensure that the boys had a proper Christmas dinner. Most of the puddings were stuffed as full of lucky sixpences as they were with hoarded raisins, and were rnixed with libations of stout or brandy.

It took all the considerable organizational powers of the Red Cross and a large slice of the resources of the Army Transport Corps to distribute, across the length and breadth of the Western Front, the largesse that came from every quarter of the globe. From America there was a shipment of beef; from South Africa, a boatload of grapes, peaches and nectarines; from Canada, 10,000 cases of red apples; and from Australia, a towering mountain of 'billy-cans' packed with comforts and goodies for the Aussies.

By 1917 the 'Christmas billies' had become a tradition. Back home in Australia, volunteers started packing them in August. Each community undertook to supply a certain number, filling each one with oddments of their own choice, and sent them in good time to a central depot from which they were shipped on to Australian soldiers overseas. It was a charming as well as a practical idea. The billy-cans themselves, as Australian as the strains of 'Waltzing Matilda', spoke of Home to the soldiers far away; when empty they were useful items to have on active service, and they were sturdy enough to be shipped without any further wrapping. They also held a surprising amount- chocolate, tobacco, cigarettes, sweets, a pipe, razor blades, soap, concentrated beef cubes notebooks, writing pads, candles, toffee, sardines, potted meat, socks and mittens (or at least a fair selection of these items) could all be stuffed in. All of them contained a different assortment, but the universal verdict was that they were 'Bonzo'.

The exception was the unfortunate Aussie who was particularly pleased to find in his billy-can a pair of socks knitted in the finest wool, and donned them for a long march. Within half an hour he was limping badly, and at the first rest stop removed his boots to look for the trouble. There were no protruding nails, nothing to be seen. The march continued, and by the time it ended the man was practically crippled by a mammoth blister on his foot. He found some water in which to bathe it, and when he pulled off the sock to immerse his foot in the soothing bath, to the ribald amusement of his comrades a small scrap of paper fell to the floor. On it was written in a shaky hand, 'God bless you, My Dear Boy.' It was fortunate that the kindly donor was unable to hear her Dear Boy's reaction.

Lord Ashcroft's VCs

Lord Ashcroft's VCs Follow Lord Ashcroft on Twitter

Follow Lord Ashcroft on Twitter

The Albert Medal was authorized by her Majesty Queen Victoria on 12 March, 1866, and

The Albert Medal was authorized by her Majesty Queen Victoria on 12 March, 1866, and

Never a word of a lie in it!

Never a word of a lie in it!

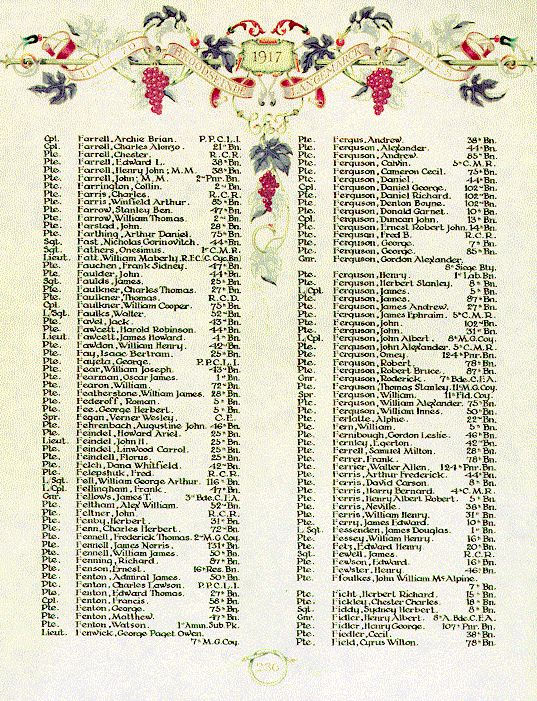

The Responsibility of Perpetuation

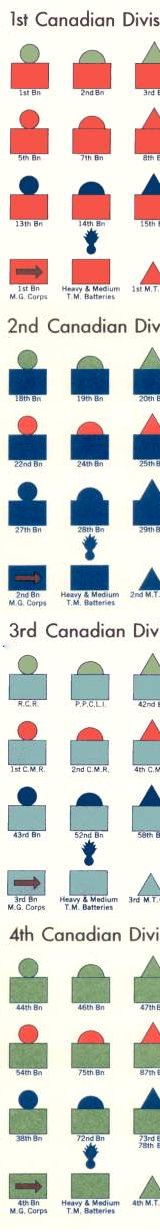

The Responsibility of Perpetuation The following shows the

The following shows the