Topic: CEF

The photo above shows an unidentified soldier of The Royal Canadian Regiment with a friend.

Both men are wearing the standard dress for convalescing soldiers — Hospital Blues.

Adjutant-General's Branch

Medical Categorization in the CEF

From the Report of the Ministry; Overseas Military Forces of Canada; 1918

For the purpose of knowing each soldier's medical condition and availability as a reinforcement, a system of medical categorization, somewhat on the lines in use in the Imperial Forces has been in force since 1917.

Medical categorization may, shortly, be described as the sorting of soldiers into groups in accordance with their medical fitness for Service.

This system created four distinct Medical Categories as follows:—

- Category A. Fit for General Service

- Category B. Not fit for General Service, but fit for certain classes of service Oversea or in the British Isles.

- Category D. Temporarily unfit for Service in Category A or B, but likely to become fit within six months.

- Category E. Unfit for Service in Category A or B, and not likely to become fit within six months. Awaiting discharge.

These categories were general classification of medical conditions, and the first three were sub-divided as follows:—

Category A into—

- A 1. – Men actually fit for Service Overseas, in all respects, both as regards training and physical qualifications.

- A 2. – Men who have not been Overseas, but should be fit for A 1 as soon as trained.

- A 3. – Overseas casualties on discharge from Hospital, or Command Depots, who will be fit for classification as A 1 as soon as hardening and raining is completed in Reserve Units.

- A 4. – Men under 19 years of age, who will be fit for A 1 or A 2 as soon as they attain that age.

Category B was sub-divided in accordance with the nature of the work it is considered by the Medical Authorities the men classified in the sub-divisions are capable of performing.

- B 1. – Capable of employment in Railway, Canadian Army Service Corps, Forestry and Labour Units, or upon work of a similar character.

- B 2. – Capable of work in Forestry, Labour, Canadian Army Service Corps, Canadian Army Medical Corps (Base Units), and Veterinary Units, and on Garrison or Regimental outdoor employments.

- B 3. – Capable of employment on sedentary work as Clerks, Storemen, Batmen, Cooks, Orderlies, etc., or, if skilled tradesmen, in their trades.

Category D into—

- D 1. – Soldiers discharged from Hospital to Command Depots who are not considered physically fir for Category A, but who will not be so upon completion of remedial training or hardening treatment.

Note:—The role of the Command Depots is to harden men discharged from Hospital before they join their Reserve Units for regular training. Under a trained staff, physical exercises and training are carried out at these Depots and supervised by a Medical Officer. When the Commandant and Medical Officer are satisfied that a man is sufficiently hardened he is despatched to his Reserve Unit and placed in Category A.

- D 3. – A temporary Category, and denoted other ranks of any Unit under, or awaiting, medical treatment who, on completion of such treatment, will rejoin their original category.

In order to obtain a uniform classification throughout, the following standards were laid down as a gide in placing men in the various Categories:—

- Category A. – Able to march, see to shoot, hear well and stand Active Service conditions.

- Category B. – Free from serious organic disease, and, in addition, if classified under—

- B 1. – Able to march at least five miles, see and hear sufficiently well for ordinary purposes.

- B 2. – Able to walk to and from work a distance not exceeding five miles, see and hear sufficiently well for ordinary purposes.

- B 3. – Only suitable for sedentary work, or on such duties as Storemen, Batman, etc., or, if skilled trade, fit to work at their trades.

It will be seen from the foregoing that category A was the highest in medical condition. The difference between category A 1 and category A 2 was purely one of training, and the responsibility for raising a soldier from A 2 to A 1 rested with the Officer Commanding the Unit in which the man was in training. The difference between Category A 1 and Category A 3 was jointly one of training and medical condition, and the responsibility for raising men from Category A 3 to Category A 1 rested with the Officer Commanding the Unit in which the man was in training., in conjunction with the Medical Officer of that Unit.

The differences in all other Categories were of a medical nature, and a soldier could only be raised from Category B or category D to category A by the Medical Authorities. For this purpose all soldiers who were placed in any of the sub-divisions of Category B were medically re-examined every month after having been placed in a sub-division of Category B, with the exception of men who were employed in certain offices or with Administrative Units, who were medically re-examined every two months. The Medical Officer making this re-examination had power to raise any soldiers in the sub-grades of Category B or into Category A, but if, in his opinion, the soldier was not physically fit for the Category in which he had previously been placed, arrangements were made for the soldier to appear before a Medical Board composed of three or more Medical Officers, and his category was determined by that Board.

All Canadian casualties, except local casualties admitted to British hospitals and discharged in the same Category as they were when admitted, were discharged, through Canadian Hospitals, and on being discharged from Hospital were placed in one of the foregoing Categories. The officer in charge of the hospital might place a casualty in Category A or in Category B, or might declare the casualty fit to be discharged in the same category as that in which he was admitted to Hospital, but if the soldier could not be classified by the Officer Commanding the Hospital, he appeared before a Medical Board at the Hospital, and was placed in a category by that Board.

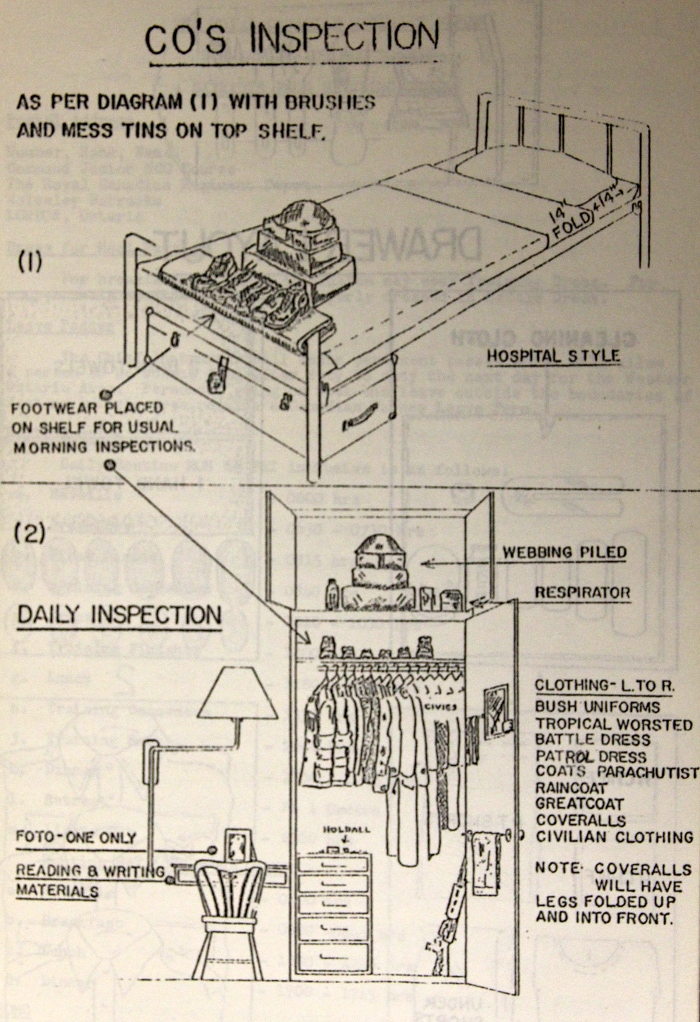

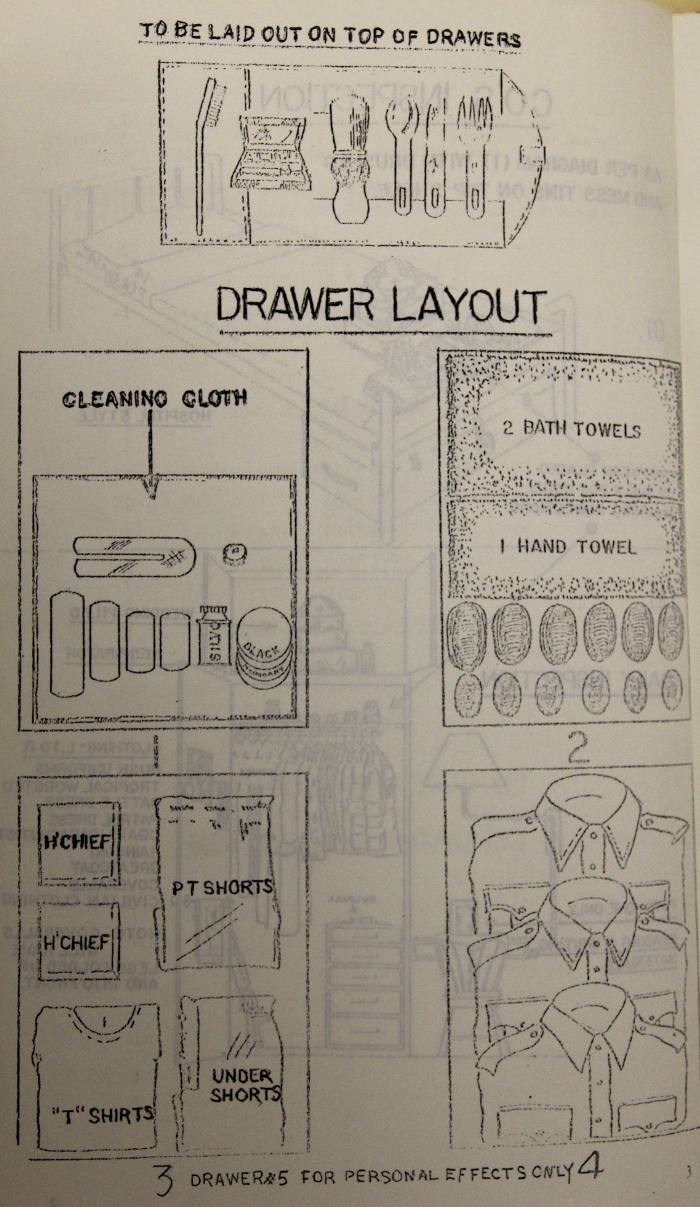

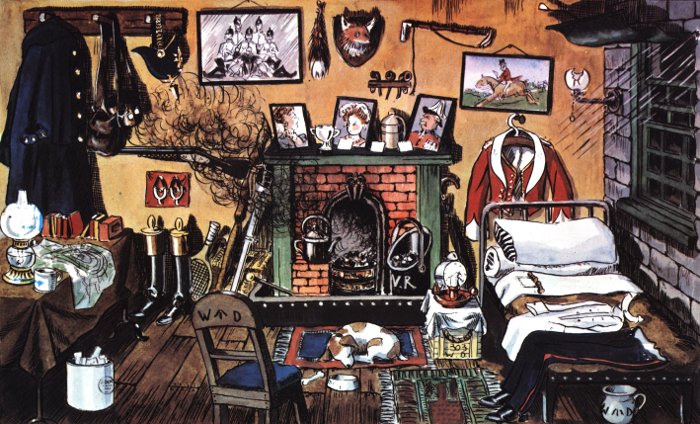

Kit Layout

Kit Layout

Submitted by Major J.S. Cox

Submitted by Major J.S. Cox

It is gratifying to record that since the Overseas Military Forces of Canada first went into action they have been awarded upwards of

It is gratifying to record that since the Overseas Military Forces of Canada first went into action they have been awarded upwards of  Chevrons for Overseas Service.—These Chevrons are issued to all ranks, and in the case of members of the Overseas Military Forces of Canada the date of leaving Canada is the date for the award of the first Chevron. An additional Chevron is issued 12 months from this date, and so on. All those members of the Overseas Military Forces of Canada who left Canada prior to midnight, December 31, 1914, are entitled to a Red Chevron as the first Chevron and a blue Chevron for each additional 12 months served out of Canada. Those who left Canada since December 31, 1914, do not receive the Red Chevron.

Chevrons for Overseas Service.—These Chevrons are issued to all ranks, and in the case of members of the Overseas Military Forces of Canada the date of leaving Canada is the date for the award of the first Chevron. An additional Chevron is issued 12 months from this date, and so on. All those members of the Overseas Military Forces of Canada who left Canada prior to midnight, December 31, 1914, are entitled to a Red Chevron as the first Chevron and a blue Chevron for each additional 12 months served out of Canada. Those who left Canada since December 31, 1914, do not receive the Red Chevron.

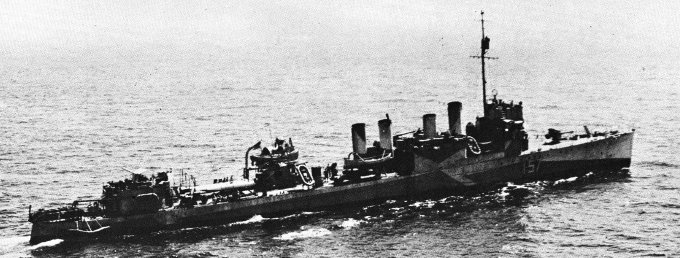

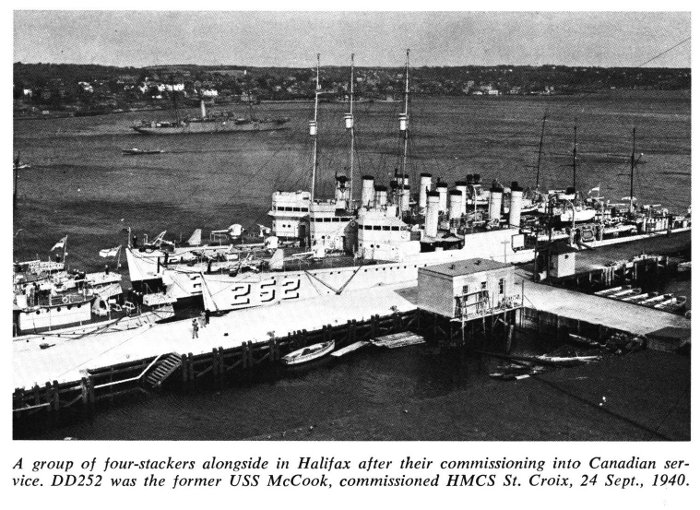

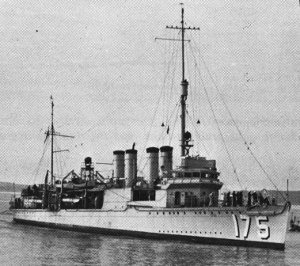

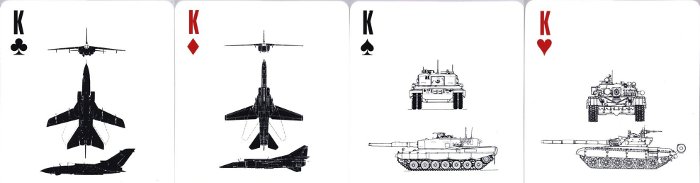

HMCS Annapolis

HMCS Annapolis

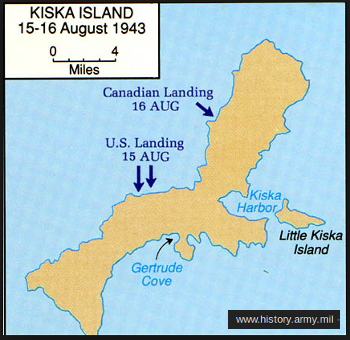

In August 1943, the

In August 1943, the

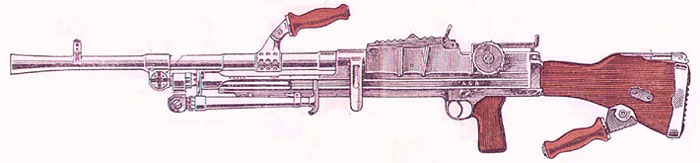

With two grease boxes, pole draught, M.D. No. 1; two

With two grease boxes, pole draught, M.D. No. 1; two